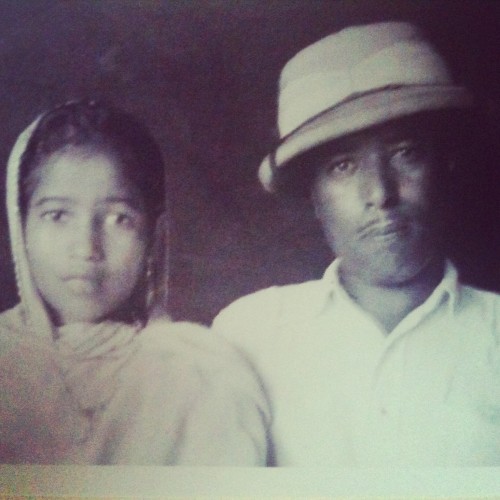

My grandfather (pictured here with my mum) reckoned his mother must have passed away around 1958 because that’s when her letters stopped coming. Until then, whether or not he wrote back, his mother made a point of conveying her news, in neatly typewritten letters to her first born, a son named Sultan Mehmood. Commencing a correspondence in 1923, which spanned some 35 years, mother and son could never have imagined that these letters is all they would have of each other.

My grandfather (pictured here with my mum) reckoned his mother must have passed away around 1958 because that’s when her letters stopped coming. Until then, whether or not he wrote back, his mother made a point of conveying her news, in neatly typewritten letters to her first born, a son named Sultan Mehmood. Commencing a correspondence in 1923, which spanned some 35 years, mother and son could never have imagined that these letters is all they would have of each other.

Sultan Mehmood was my maternal grandfather, but everyone – friends, family and colleagues – knew him as Babu Jee, an honorific title given to an educated gent. My relationship with Babu Jee began when I was four after we left Keighley to settle in Rawalpindi. I remember Babu Jee being a humble man, working as a clerk and returning on his bicycle every evening, with a bag of broken biscuits to treat the eight grandchildren that lived in his household.

You know how it is. Your grandfather is just that. So, as I grew up under his loving gaze, I never gave a second thought to the distinctive tight woolly curls on his head, or his striking dark colouring. Sadly, it was only after Babu Jee had passed away in the late 1980s, that I came to learn that he had inherited his curls and colouring from his mother – a native of Mozambique, of Christian faith.

The story goes that Babu Jee’s father (my great grandfather), Seth Jahandad Khan, left our ancestral village of Nila (in what is now Pakistan, but was then undivided India) following a family disagreement around the year 1900. We know not how or why, but he ended up boarding a ship from Bombay to Beira in Mozambique. In Beira he settled, making his fortune from orchards, and that’s also where he met and married Anna, his first wife.

Anna bore her husband seven children. Born in 1909, my grandfather had barely reached his teens when he, along with most of his siblings, was sent back to Nila, to live with his father’s parents. It must have been quite a culture shock. Not only did Sultan Mehmood and his siblings have unruly afro hair and dark skin, they also didn’t speak Urdu or Punjabi. Their arrival was marked with much celebration in Nila where my great grandfather had been given up for dead. The arrival of his six strapping children, ranging in age from thirteen to four, signified not only that he was alive but also that he was thriving. A halwai (sweetmeat maker) was hired to set up in the yard to serve the many visitors that came to gawp at these dark skinned creatures, who seemed equally bewildered by their new surroundings.

Within a year, Babu Jee was enrolled at the prestigious Islamia College in Lahore. I still have the Bible he was issued by the British missionaries that ran the college, inscribed with his name and dated 1925 in my grandfather’s distinctive handwriting. The irony is that for all these years, I’ve regarded that Bible as a symbol of Babu Jee’s liberal outlook, but it never occurred to me that this holy book might have had a deeper spiritual meaning for him.

Back in Beira meanwhile, Anna’s youngest child, a boy named Sarandaz Khan, remained with her because he was still being breastfed when his siblings were repatriated. When her husband eventually remarried and returned to Nila to join his children, Anna was left to raise her youngest singlehandedly. She was never to see any of her other children again. To mark her loss, she named some of Sarandaz’ children after the ones she had lost.

It was when I was at university as a mature anthropology student, about fifteen years ago, that I became interested in researching my family history. On a trip to Pakistan around that time, mum encouraged me to speak to Babu Jee’s last surviving sibling, his jovial younger brother Behram Khan. We spent many hours recording his story. Although he didn’t remember much, this octogenarian was close to tears as he recounted the memory of being plucked away from his mother at the tender age of four. That extended private audience with my grandfather’s younger brother was poignant in so many ways, not least because he passed away just four weeks later.

Now, some ninety years on since these heart-breaking events, my daughter marks the fifth generation of Anna’s lineage. The time has come for my mother, daughter and I to travel from Bradford to Beira to retrace the footsteps of my African great grandmother. Sarandaz Khan’s children and grandchildren are still settled there. The ancestral home is still standing. Mum wants to see where her father was born, and she wants to say a prayer at Anna’s graveside on his behalf. We want to hear their version of events. We want to try and understand what caused my great grandfather to divide his family so dramatically.

Although we’re still strangers to one another, I can’t help wondering if we will look alike. There will be many questions and tears no doubt. Each new communication between Beira and Bradford builds the excitement and anticipation. Earlier this week I received an email from Aunt Eva, who introduced herself as Sarandaz’ daughter. “Greetings from Mozambique to my cousin and all the family,” she began. “Please bring lots of photos. There’s a lot of catching up to do.”

You may also like to read the second part of this blog, My African Roots, written after the trip to Mozambique.

Irna Qureshi blogs about being British, Pakistani, Muslim and female in Bradford, against a backdrop of classic Indian films.

Wonderful story – hope it turns out as richly as it sounds – have a great time –

What a heartbreaking story. I had tears in my eyes while reading it.

All the best for your visit to Mozambique

Regards to Appa and love to Noori

wow, such a lump in my throat as I read that….

Thanks for sharing a great story. It just goes to show that no matter what, we all have a shared humanity that goes way beyond racial boundaries. I know you will have a great time in Mozambique with your newly found African family. Best of Luck !

Thanks everyone for your good wishes.

wow Irna Baji!!this is amazing!!:)

whoah this weblog is wonderful i really like studying your articles. Stay up the great work!