Guest blog post by Irna Qureshi

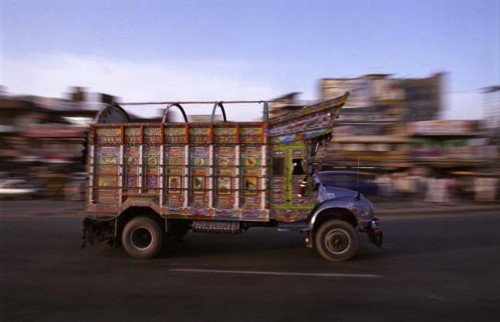

It’s an odd relationship I have with photographer Tim Smith. Over the last 15 years, we’ve collaborated on several exhibitions which we’ve developed into books, where we use my oral history stories with Tim’s photographs to weave a narrative. Our latest venture, an exhibition and book titled The Grand Trunk Road: From Delhi to the Khyber Pass, involved a five week long, 1,000 mile road trip between Delhi and the Khyber Pass – attending weddings, funerals and religious events; schools, barber’s shops, factories, mosques, temples and cathedrals – wherever people were willing to talk to us. We weren’t just telling the story of the Grand Trunk Road, the oldest, longest and most famous trade and military highway in the Indian Subcontinent; a road described by Rudyard Kipling as “the backbone of all Hind – such a river of life as nowhere else exists in the world.” We wanted to explain the crucial role that this road has played in the process of migration from North India and Pakistan to Britain. The road runs from Calcutta in India all the way to Kabul in Afghanistan. But we were interested in the stretch between Delhi and the Khyber Pass, which travels through the homelands of over 90% of British Pakistanis and the vast majority of British Sikhs and Hindus from the Indian Punjab.

When the British ruled India, they built garrison towns along the Grand Trunk Road, in places like Jalandhar, Ludhiana, Lahore, Jhelum, Rawalpindi, Attock and Peshawar. They also recruited locals from these areas into the lower ranks of the army. We wanted to find former soldiers and sailors who had joined the British Army or the Merchant Navy before settling in Britain, since these were the pioneers that started the process of chain migration. They realised there was good money to be made in British factories and foundries in the 1950s, so they sent word back home and invited their families to join them.

Tim’s vocation of photographing Britain’s Asian communities means he knows his halal from his haram, and his mosque from his mandir. Conducting extensive fieldwork in India and Pakistan though, took our working relationship to a new level. Tim doesn’t speak Urdu or Punjabi so I translated for him. I was familiar with the local culture while he brought a fresh perspective. While Tim’s tall build, fair colouring, awkwardly worn shalwar kameez and expensive camera kit casually slung over his shoulders made him stand out a mile, I thought I blended in quite well. Obviously, travelling around parts of India and Pakistan with a male companion did make me feel less vulnerable. And yet, travelling with a white man that I wasn’t married to was at times – well – awkward! At best there was curiosity, at worst disapproval.

I got my first telling off, so to speak, in Delhi. Inside the magnificent Jama Mosque, a Muslim man was curious to know how I was related to the photographer I was with. I made the mistake of being honest, although I quickly added that our respective spouses and children were waiting for us back in Britain. Well, that was it. He followed me around the mosque holding a dodgy looking carrier bag, extolling the virtues of stay at home wives and daughters. I realised then that I needed to deal with this delicate situation more strategically, to stop people feeling uncomfortable, and to save me from being perceived as too progressive which could jeopardise the fieldwork. And so, in the name of research, I learnt to smile shyly and practiced saying nothing when people enquired, “Is the Britisher your husband, miss?”

Someone advised us to go to a village called Saleh Khana, a few miles off the Grand Trunk Road. The British had built a cantonment in nearby Cherat, and villagers had been recruited to run the canteens for the locals recruited into the lower ranks. The Saleh Khana folk picked up this profession to such an extent, that when the British invaded the Falklands, the canteens were run by people from Saleh Khana. Thousands of people from Saleh Khana now live in the Midlands. I was, as ever, wearing a chaadar (shawl) which covered my head and body really well. But I realised too late that every woman in Saleh Khana was wearing an Afghan style blue shuttlecock bhurka popularised by BBC News 24. All was well until an elderly lady stopped and glared at me in the street through the meshed cloth that covered her face. “Who is she with?” she asked loudly. An unaccompanied woman wandering around the village, a white man in tow, and no bhurka to boot – I was absolutely mortified!

Back in Peshawar, I urgently found a bhurka shop early the following morning. I never knew there were so many varieties. I bought several styles. We were visiting another village that afternoon, Wesa near Campbellpur, from where thousands of people have migrated to Bradford, Oldham and Sheffield. I wore my new embroidered black chiffon bhurka with a separate veil that covered my head and face – only my eyes were visible. The fabric’s fall had a wonderful feel and flow to it, and I felt bizarrely sexy. But in the April heat, I was soon feeling sweaty, propping up the fiddly veil and trying not to trip up on the bhurka’s hem, but it felt good to fit in. I felt armoured, assured, acquitted.

I was interviewing a man in his fifties who divided his time between Wesa and Bradford. He was telling me about working in a foundry in Sheffield when he stopped and asked, “How do you know that man?”

“He’s my husband!” I replied indignantly.

“Yes, I know,” he continued smugly. “I asked him too and he said the same thing.”

“Thank goodness for my bhurka.” I smirked privately. “Even if I bump into you back in Bradford, you’re not going to recognise me!”

The Grand Trunk Road: From Delhi to the Khyber Pass, oral histories by Irna Qureshi and photographs by Tim Smith, a book from Dewi Lewis Publishing (2011).

Irna Qureshi also blogs about the social history of Indian cinema in Britain at www.bollywoodinbritain.wordpress.com

Some recent reviews

The Observer

The Independent

Go on get yourself a copy!

Riwaaz Weddings are here to make the weddings enjoyable and memorable for you and to provide that perfect touch. Making your special moments an unforgettable celebration, we at Riwaaz provide personalized and innovative wedding services. Wedding is a difficult undertaking. You won’t have the fear of missing even a single event till as long as you have the Riwaaz Weddings planners. Wedding is a valuable gift that every parent would want to enrich in their children life and “Riwaaz Weddings” only makes it easier for you. Marriage is a unique event. You have seen your children grow at every stage and now it’s time to give them few memorable moments which you all can cherish throughout your lives.Weddings in Punjab