Guest blog by Louise Atkinson

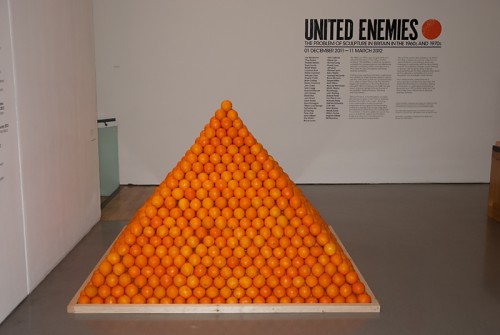

As I ascend the steps of the Henry Moore Institute, I’m hit by a sickly sweet, citrus smell that pervades the air in the gallery foyer. The scent in question emanates from a large pyramid, originally made up of 6000 oranges, which visitors are invited to remove one by one. It’s been well over two weeks since the opening, so I do the greengrocer squeezy test to determine the ideal candidate for consumption, but quickly decide that they might be past their best.

As introductions to exhibitions go, this one sets out its stall pretty well. ‘United Enemies’, while by no means a survey of the 60s and 70s sculptural landscape, gives a good indication of the kind of questions that were raised by artists in that period. What appears, at first glance, to be as innocuous as an overly large fruit bowl, actually allows the audience a greater sense of interaction with the artwork, through touch, taste and smell, as well as visually. Even on a conceptual level there is a new appreciation of spatial awareness, social responsibility towards the preservation of the artwork and what classifies as ‘art materials’.

Equally contentious is the show’s title, referring to the ‘problem’ of sculpture in Britain. Although, deliberately provocative, it occurred to me that this reflected accurately the issues that artists were facing at the time and exposed new audiences to ask those same questions: So what is the problem with British sculpture?

My first reaction was to disregard the term ‘problem’ and was instead drawn to the idea of British sculpture. What makes a sculpture British? The curator had selected works by a specific group of artists who were working and exhibiting in the UK at that time, but I wondered whether there could be any defining factors other than geographic location. Indeed, some of the more prominent exhibitors in the show, including Roelof Louw, creator of ‘Soul City (Pyramid of Oranges), were born and grew up outside the UK.

I began questioning whether there were common traits or sensibilities particular to this type of art practice, disparate though it was, that revealed a sense of Britishness, despite the nationality of the maker. Then, in amongst explorations of sculpture as performance, installation, photography, sound and kinetic works, I found the common thread, that of absurdity and playfulness. Each artist appeared to revel in self-deprecation for comic effect in almost stereotypical British fashion. This allowed a sense of freedom, not only within the artwork, but also in the viewer, as they were silently invited to ‘play’ with the art. The smiles on faces of gallery-goers as they discovered a mischievously hidden message, reminded me of the power of art to surprise and delight.

Another interesting discovery was how contemporary the work seemed, and in no small part reflected in the work of the Young British Artists of the 1990s such as Gavin Turk, Jake and Dinos Chapman and Sarah Lucas. So what was the problem again? Some of the older works in the show were too fragile to touch, despite being designed to be kinetic, so although the artists of that era were breaking new ground in form and materials, perhaps the biggest problem was one they couldn’t have anticipated at the time of making. This, the problem of all art, that when it becomes institutionalised, inevitably loses some of its playfulness due to issues of ownership and conservation. Luckily within this exhibition, we are given the opportunity to imagine this interaction, even if we can’t experience it directly. And if nothing else, maybe you’ll think differently the next time you’re buying oranges.

The Problem of Sculpture in Britain in the 1960s and 1970s

1st December 2011 – 11th March 2012

Main Galleries