What is to be done? the title of the new exhibition at The Henry Moore Institute, probably alludes to Lenin’s famous polemic of 1902, though Mario Merz prefers the story that the phrase originates from a children’s game he apparently observed on a street in Turin. The kids kept on asking “what is to be done?” Not having the answer didn’t seem to deter them from playing. Lenin, however, always wanted an answer. Always thought he had the answer. He counterposed the “spontaneous” (childlike) consciousness of the masses against the ideologically corrected consciousness of the vanguard, the ones who know. This clever juxtaposition gave me a clue how to approach the exhibition.

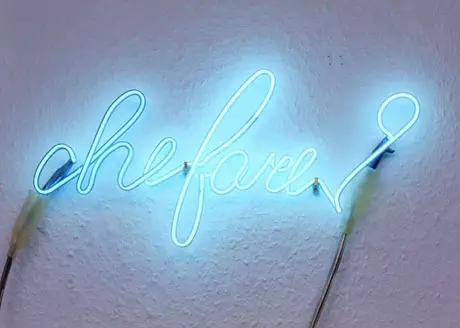

My spontaneous reactions tend to be quite childish. The first thing you see when you go to the Merz exhibition are the words “Che Fare?” in brilliant blue neon about eye height on the wall facing you. It looks like handwriting, quite spidery and delicate – actually, it looks like it’s been written on air, a kind of after-image, as if it may fade quickly and turn dark and ghostly. Then you notice a plug. I want to switch it off and then on again, just to see what happens.

When you turn around you notice you are between two structures; a small igloo (actually, how big is an igloo anyway? I’m only assuming this is a scale model) with some neon words around the top – their position makes it hard to read, but it’s handwritten again, though this time in capital letters; and a tall, frame structure, which at first looks like the skeleton of an unfeasibly large brolly. Both structures are inviting. The igloo looks solid at first, until you notice it’s built from hundreds of small white rectangular bags stitched across the middle of the long side, so they look like tiny pillows, somehow fastened together to make a dome. Why don’t they collapse in a heap? Maybe there’s a frame inside? It would be good to crawl in there and find out. The metal structure is big enough to run through – well, I’d have to duck, but I reckon I’d manage – and it is tempting to thread in and out of the legs in a kind of maypole dance. The contraption looks like it wouldn’t collapse if it took a knock or two, and it seems bolted to the floor somehow, so you’re not going to knock it over.

In the next room there’s a large cone basket, a man-sized cone, big enough to hide in, made out of withies. For some reason I want to push this over; perhaps because it reminds me of a skittle.

There are six large plates of glass leaning against a wall, arranged in pairs tied together in the middle by rods of neon so it looks like three doors (or windows?) At the foot of each pane there are a couple of brown, heavy looking blocks with a groove down the centre, which seem to hold the glass steady. At the top of each piece of glass there’s some writing; it’s Italian, not particularly neat – I almost said “scrawled” and I realise I’m quite annoyed by the untidiness – and in red! If I had my way I’d scrub that out and make Mr Merz start over again! I’m not sure quite why I like the scribble in neon but not in what looks like lipstick.

To the right and above my head there’s a row of neon words. Italian again. But this time the letters are standardised, corporate almost, so the message seems to come from on high – literally. Eight words, arranged in four pairs. Mainly blue neon, but the fifth, seventh and eighth in a kind of orangey red. Even though I don’t understand the words I feel called upon to do something. There’s an imperative. But it’s weirdly immobilising.

In the middle of the room there is what can only be described as a car. That’s because it is an actual car. A Simca 1000 (and here is my interesting fact of the day, something you won’t find in the catalogue; the Simca 1000 began production on July 27, 1961, exactly 50 years ago. Happy birthday motor car! We should have brought cake.) It’s dirty, spattered with mud or clay maybe, but seems to be in decent condition. There’s a roof rack holding a thick slab of orangey wax. And, most strikingly, a bloody great spike of neon zapping through the drivers side window . . . it looks like it’s been twocked by Thor. I want to jump in, grab the wheel, thump the horn, spring the boot and jump start the engine and make a break for the Headrow . . .

The next room has a few more pieces, including a large lasagna tin full of wax which melts in the heat of the neon “Che Fare?” written on the surface. But my favourite here has to be “Bottiglia,” an upturned wine bottle G-clamped to a shelf at a jaunty angle – not quite perpendicular, as if mimicking the action of convivially draining the last of the vino – pierced by a hook of white neon which makes the green glass glow. I wanted to grab the bottle and fetch a refill. Merz said that “wine represents energy that passes through the body and alters feelings and perceptions.” My kinda guy! I can’t alter my feelings and perceptions enough.

Of course, I behaved myself. I have a fully functioning super-ego, an intact conscience, and a set of inhibitory responses that wouldn’t be out of place in a monastery. Merz’s work remained unmolested. I managed to maintain my dignity. Still, if any of the staff rumbled what was going on in my head I probably wouldn’t be invited back. I’m sure that’s not how we are meant to think of the exhibition.

In fact, what we are meant to think is detailed in the exhibition notes and the extensive essay by Head of Sculpture Studies, Lisa Le Feuvre, “Protagonist Materials.” I’m sure there’s a copy in the rather marvelous library they have there. It’s worth a read just to find out a bit about the cultural background and political situation in which Merz grew up and responded to. Merz was part of a movement called Arte Povera, which “literally translates as “poor art”, but crucially povera refers to objects activated through use, rather than to a paucity of wealth.” I’m not really sure if I fully understood what Arte Provera was all about – or perhaps I should say I was suffering from a “paucity of comprehension!” – but artistically it had something to do with using common, cheap, often reclaimed material, and making works that were some kind of comment on everyday life. Politically, the movement was anti-capitalist and vociferously anti-American. This raised a bunch of questions for me.

If art is made specifically as a reaction to a time and place how can it have the same “protagonist” abilities years later in a different context? I don’t know much about post war Italy; most of the materials and references that Merz deploys are lost on me. Can I enjoy it anyway?

What happens to “poor” art when it enters the gallery, when it circulates as a commodity on the art market? Merz is worth a bob or two, isn’t he? No matter how “budget” the car was it is now a valuable object; please, do not touch the exhibits!

And, should we really believe all the political posturing? The guy who invented the term Art Povera, traded the objects and peddled the ideology of “simultaneous revolution in art and politics” and hatred of the “domination of art world discourses by the North American voice,” ended up as Director of the Guggenheim . . . so much for criticising art as a “tourist activity for the rich.”

I don’t expect any answers. In the spirit of Mario Merz I’m content with the questions. Go and see the exhibition for yourself.

Mario Merz: What is to Be Done? 28 July – 30 October 2011

Henry Moore Institute, The Headrow, Leeds, LS1 3AH.