Tuesday morning I was listening to Michael Portillo’s Democracy on Trial on Radio 4. He interviewed Dr Rana Mitter, a professor of Modern Chinese History at Oxford, who told a revealing story about a TV talent contest held five years earlier called Super Girl. The show was incredibly popular, watched by upwards of 400 million people. Something like 3.5 million people texted their vote. Such an outburst of popular participation made the ruling Communist Party nervous, thinking it may set a precedent; the masses may get the idea that their opinion counted. The China Daily wasn’t pleased: “How come an imitation of a democratic system ends up selecting the singer who has the least ability to carry a tune?” The government demanded that the TV producers withdraw the term “vote” and replace it with “make a suggestion.” “Voting” is an exertion of power, an expression of confident citizenship; a “suggestion” recognises that subjects should keep their mouths shut and that the authorities have the final say. A “suggestion” doesn’t really count.

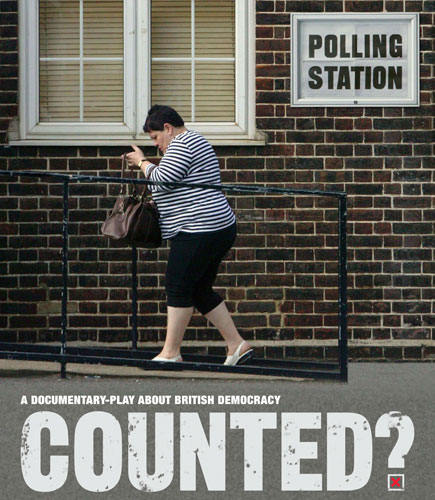

I was still thinking about this later that evening when I went to The Courtyard Theatre at The West Yorkshire Playhouse to see Counted, which advertises itself as “a documentary play about British Democracy.” I wasn’t exactly sure what a documentary play was but I was fascinated by the background research project. The play is a sort of montage of tiny episodes taken word for word from interviews carried out by Leeds academic Stephen Coleman. He talked to people in youth clubs and golf clubs, Sure Start Centres and prisons, in the street and in wokplaces. His research explored how individuals experience the process of voting, from the intimate aesthetics of the polling booth to the major public ritual of campaign and commentary. He asked simple questions; “what does voting mean?” “what would make it more appealing to you to vote?” From this mass of material the theatre company selected small representative episodes, and ordered, shaped, and reimagined the academic investigation for the stage. Reality isn’t completely ironed and tidied away in the interests of a smooth narrative; characters talk over each other, falter, fail to find the words they are looking for and often don’t quite finish a sentence, just like people do in real life. Apparently the actors spent ages listening to the tapes and practising “to get the music right.” The effort definitely paid off. It might sound dull and worthy if you just read about the background and the method, but the play was oddly captivating.

As a theatrical device verbatim repetition can have some powerful political effects. For instance, in the last American Presidential Election, Tina Fey’s impersonation of Sarah Palin, based entirely on actual speeches and tv performances, wouldn’t have been any where near as stinging if the words had been made up, and it wouldn’t have had the same political ramifications. The comedy, the political punch, derived precisely from it’s scrupulous reframing of the real. In Counted the effect is the same but the intention is precisely the opposite; not to poke fun at the pretentions of the powerful but to elevate the ordinary, the common, the powerless. Counted is no less funny (there are plenty of good jokes, and all of them from the mouths of normal people) and just as telling.

The first voice in the play, besides the academic investigator, is a recording (part of the actual interviews I’m guessing) telling us how lonely and isolating voting is, something almost embarrassing. Voting has to be done behind a screen as if to protect our dignity. Oddly the polling booths on stage did resemble cubicles, changing rooms, or toilets, as if to emphasize that the vote is a private moment, not done in the public gaze.

Six actors then take the stage. They have a huge array of characters to portray with just a quick change of clothes, a readjusted accent, and the minimum of props – a newspaper, carrier bag, football, or box of Crunchy Nut Cornflakes (or it may have been a proprietary brand, hard to tell from where I was sitting.) They manage to move swiftly and seemlessly from stroppy adolescents (voting is “so gay!”) to distracted OAP’s, entirely believably. The range of characters they pull off is quite incredible, from a middle aged lady running the Whoops a Daisy florist in Featherstone to a Glaswegian young thirty-something prisoner, elderly gent from Harrogate to young Afghan man with halting English. Each conversation added a new facet, a different aspect or association, and there was a sense that these points of view could proliferate easily without end. There was no attempt to impose a coherent plot or to privilege one position over any other. Every story kept the audience interested, empathetic, questioning, and occasionally annoyed at what they were hearing – just like in real life we had to listen to things and react to viewpoints we might not find agreeable.

Some of the stories are sad, like the young Muslim girl hounded and harrassed by her own family. Some are unsavoury, like the silly old sod who votes BNP in infantile protest about his diminishing rights as “white ethnic English man.” Some are incendiary, like the young bloke from New Fryston angry about the imposition of a High Art Landscape and Sculpture when the locals really wanted a kids’ play ground; “When they knock on your door and specifically ask you what you want, and you tell them what you want, and you get THIS . . . ” The most affecting story for me was the Afro-Caribbean woman who told of her family’s alienation as the only black people on a bleak South Leeds estate, how she’d finally gained acceptance and the right to vote in peace at the same time as noticing for the first time ever there were BNP posters in her neighbours windows. While she told her story a picture of a typical Middleton Street (Sissons Road I think, “top of the Avvy” as the locals call it) was projected onto the screen behind her. I lived on the same street for a while in the 70’s. I went to the local single sex comprehensive, Parkside. Five hundred plus boys, only two Asian and one black kid . . . I must have gone to school with her son! This thought hit me with a thump; this wasn’t just “a play” it was a real chunk of hard, gritty reality too, and I was implicated. It wasn’t just entertainment any more, I was involved, potentially part of the problem, hopefully part of the solution. It made me wonder what more I could have done back then (when I was much more politically active,) what my friends and I did wrong, and if there was any way we could make it right. It made me reassess, just a little, my own political past. It made me ask the more difficult question that the play raises; not, what would make me feel counted, but what can I do that counts. And this is the message that comes through most strongly; we all have our cynical moments when we just disengage and mock the idea that we can influence things for the better, or we disparrage people who are trying to change things, little by little, locally. But we genuinely admire the people who have the energy to make things happen, even if it’s just a new set of traffic lights or saving a swimming baths. The world is a better place because of people who interfere. Who stand up to be counted.

It isn’t a matter of stutus, knowledge, or ideology. The play makes clear that everyone counts, we just have to change the way we see things. As George Burns wisely said, “Too bad all the people who know how to run the country are busy driving cabs and cutting hair.”

Keep posting stuff like this i really like it