On BBC4 this evening, at 23:10, there’s a film playing – from Leeds’ own production company Human Film – called Son of Babylon. Well I saw the film during the 2010 Leeds International Film Festival, which I was covering for Film & Festivals magazine. Below is my review from the night, and excerpts from the post film q&a.

On BBC4 this evening, at 23:10, there’s a film playing – from Leeds’ own production company Human Film – called Son of Babylon. Well I saw the film during the 2010 Leeds International Film Festival, which I was covering for Film & Festivals magazine. Below is my review from the night, and excerpts from the post film q&a.

The film was preceded by an introduction from the director, Mohamed Al Daradji, who described it as a homecoming event, for although it was shot and set in Iraq, it was produced in Leeds. Mohamed, an Iraqi born filmmaker, lives in and completed his education in the city.

Review

The fact that it was produced in Leeds and that the filmmakers learned their trade in the West makes a telling contribution, as the film adopts formulaic road movie genre functions (a tried and tested method of portraying physical, existential and socio-cultural journeys). Yet this road movie’s beauty comes from having such an honest, genuine and fresh perspective.

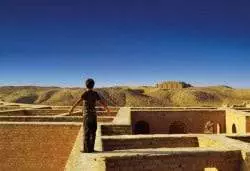

Set three weeks after the fall of Saddam Hussain’s regime, the film follows the young Ahmed and his Kurdish grandmother through Iraq as they search for his father who has been missing for twelve years, having been forced to become a soldier and torn from his passion for music.

In showing this child’s journey, the film also illustrates the journey that Iraq is currently undertaking; the past that brought it to this present, and a glimpse of possible futures. The bilingual Ahmed, who can speak both Kurdish and Arabic, is juxtaposed against his elderly grandmother who is hampered by her inability to speak Arabic. He represents the youth of the country and hope for the future, which belongs to the young.

Although the American and allied forces feature as an occupying presence, the film never veers away from its main focus: on Iraq, Iraqi people and their concerns for the future. I thought this was a wonderfully subtle and adept way of acknowledging the occupation of Iraq, while asserting that the only way forward is for Iraqis to find and make their own future.

Although the American and allied forces feature as an occupying presence, the film never veers away from its main focus: on Iraq, Iraqi people and their concerns for the future. I thought this was a wonderfully subtle and adept way of acknowledging the occupation of Iraq, while asserting that the only way forward is for Iraqis to find and make their own future.

It would be some stretch to describe this as an uplifting story but there really is a well crafted optimism at its heart. Speaking of of well crafted, the landscape was used within the cinematography with such striking effect that the country really does adopt its own character.

After the screening, Mohamed took to the stage and humbly and admirably insisted that he is by no means the only force behind the film. The Director proceeded to call up many from the crew along with a representative from Screen Yorkshire, who were credited as being an essential factor in producing this film.

Isabelle Stead (Producer) spoke about the Iraq’s Missing Campaign (IMC), which the film is supporting. IMC was established to campaign about and provide support to the relatives of missing people in Iraq. Isabel explained that nobody in the United Nations, nor any department that they spoke to would take responsibility for, or supply them with the statistics regarding missing people in Iraq that they wanted to show before the end credits. The campaign intends to pressure the UN into doing something to address this problem. You can show your support for the Iraq’s Missing Campaign by signing their petition and joining their Facebook group.

Short Q&A with the director Mohamed Al Daradji

Any spoiler questions have been left out, but one did lead Mohamed to explain that whenever he got stuck creating the character of Ahmed, he based it on his own experiences and feelings at a similar phase in his own life.

When did you shoot the film?

October 2008 -March 2009. Mohamed explained that a great deal of the shooting was a little problematic, but Nasiriya was a nightmare. The Mayor gave him permission to shut down the square, but during shooting, called and asked who gave them permission to do this! He said that he may lose his job and therefore they needed to wrap up in two hours despite having at least eight hours of planned shooting left that day.

October 2008 -March 2009. Mohamed explained that a great deal of the shooting was a little problematic, but Nasiriya was a nightmare. The Mayor gave him permission to shut down the square, but during shooting, called and asked who gave them permission to do this! He said that he may lose his job and therefore they needed to wrap up in two hours despite having at least eight hours of planned shooting left that day.

How -as an individual –did it feel returning to Iraq?

Mohamed explained that alone, he is very afraid, but surrounded by family and friends it feels really good. He said that it’s amazing to see how the country is coming along; that it’s getting safer and more secure all the time. The Iraqi army and police -which they would much rather use than private security companies -were very protective and very helpful.

What was it like, shooting the scenes with the mass graves?

All the mass graves were produced, rather than shot on location, which was out of respect for all individuals and families involved. However, all the women at the mass graves in the film had lost loved ones and agreed to feature in the film in support of its cause.

Finally there was a difficult question from a man who had recently been to the northern regions of Iraq, and claimed that the characters being able to travel through borders so easily was implausible. Mohamed dealt with this tricky question in a very sensitive, but thorough manner and justified this feature of the story as the film was set three weeks after the fall of Saddam, and the chaos which ensued caused these checkpoints to break down. He further ratified his point by stating that the actress who played the grandmother had actually made that very journey.

So either tune in, set the variously branded digital recording ‘+’ devices, or even catch up with it on the BBC iPlayer if you’re reading this after its initial screening.

Mike McKenny is The Culture Vulture’s film editor. If you have any film related stories/articles/reviews, etc, contact him on [email protected] or find him on Twitter @destroyapathy.

‘Son of Babylon’ will be on BBC IPlayer all this week – please watch and share widely to boost support for independent film in Leeds!

http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b0170qbz/Son_of_Babylon/

Thanks Kathryn, I was going to put that link up myself.

Cheers.