Culture Vulture Rich Jevons talks to Henry Moore Institute’s Head of Sculpture Studies Lisa Le Feuvre about the Gego: Line As Object exhibtion in Leeds.

Would you like to introduce Gego as an artist for people haven’t come across her work before?

I’d love to, and that’s what this exhibition is all about. Gego is an artist who, really across five decades, explored the ways in which a line can be an object. What Gego did that I think is so significant is that she looked to give the line a life of its own. There’s a brilliant artist’s book in the Upper Sculpture Study Gallery called Autobiography of a Line; and if you think autobiography, you’re making it tell its own story.

So from a simple artist’s book to a complex collection of sculptures like this, she is saying that artwork has got a life of its own: It’s animate, it lives in the world. And she’s telling us as human beings to do that same thing.

I was interested because she negates the idea of her work as sculpture full stop in a quote – how much of that is her posturing or how much is that to be taken on board as an indication of her intent?

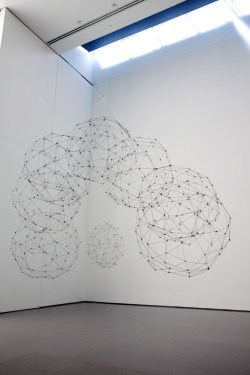

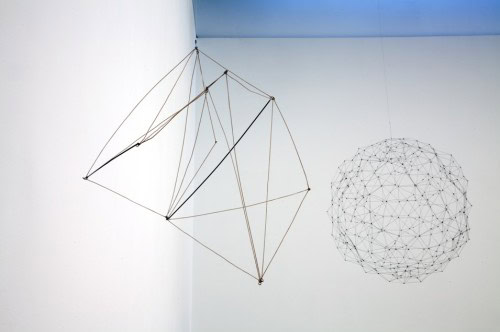

It’s a really good observation that you’ve made there. Gego said: ‘Sculpture is never what I do.’ And it’s because she understood sculpture as being heavy, immovable, three-dimensional, almost in a way that the sculpture dictated to us, the people encountering it, what to do. That’s not what Gego wanted. She wanted her sculpture to defy gravity, to work with light, to encourage us to think for ourselves.

So in a way, when she said that, it was really early on in her time as an artist, and at that point sculpture wasn’t ready for Gego, now in 2014 sculpture is ready. She’s been waiting and now really is the time to think about embracing her and thinking of her work in a sculptural perspective.

It’s been an ongoing thing with sculptors to defy gravity and to defy balance to a certain extent. When you were curating the show was that part of what was on your mind for this particular room (Gallery 2) with the work floating in space as it were?

We didn’t want the work to touch the floor or the walls, we wanted it to be really light and here at HMI we are blessed with this beautiful room where you can see natural light at six and a half metres high and we’d always imagined that we would see these sculptures in space. If you look up there at that sphere, it’s gently moving and it’s moving from us being in here.

So we always saw this room as being about lightness, so when you enter [Gallery 1] it’s a quite intimate, slow encounter and then you enter this tall room and then you go into another intimate encounter in Gallery 3 and then when you cross onto the archival space you see all the works on paper.

What’s interesting in the way it runs through it, as well as the idea of line, is the geometry which has a natural sense to it: you could compare things to beehives, or fractal notions and things.

Gego was really interested in all of that so we’ve got another exhibition looking at Darcy Thompson’s book On Growth and Form which is written in 1917 and it’s all about naturally occurring mathematical patterns. And Gego had an incredibly mathematical brain who really understood logic, form, geometry and the ways in which it occurs in nature.

Weaving is in the title Tejedura and is a very natural craft.

Yes and it’s also something that you do with your hands so that sense of thinking with the hands. All of the work Gego made herself, every single piece and you cna imagine how your hands would manipulate each of these components to create these incredible spheres.

If you look in the small works called Bichos you see the same components that she’s using in a smaller scale – it means either a bug or a creature or insect but it’s also used colloquially so you might in a friendly way refer to someone as a Bicho, a silly thing. And it also refers to insignificant objects. So she is turning these materials in her studio into something wonderful.

And then some of them are called Bichito, and –ito at the end of a word in Spanish makes it small, so it’s a little creature.

I was impressed how the whole of the exhibition is more than the sum of its parts – you’ve got the detail and intricacy but then builds up into a work of art in its own right.

That’s always something that is very imporarnt to us for our exhibitions, We always think about building an exhibition from all of the works. To make an exhibition each work has got to operate on its own terms and it needs to be a good neighbour. If you do that you can really grow an exhibition.

The idea of line and the linear – what’s the importance of that here?

What Gego’s doing is taking a line and building it up and building it up so if you see in the very early sketches from 1965 or even in the sculpture from 1957 it’s a line that has been built into an object. Gego was faithful to the line throughout her whole artistic career and the title Line As Object is really a synopsis of everything the work is concerned with: Building a line into an object. Lines are things that human beings use to understand their place in the world, they occur naturally and, really importantly, they link two positions. So it’s about a relational attitude to the world.

Just one more observation was that some of them, not all, have actually got a kind of optical art effect, especially the drawings, you think of [Bridget] Riley.

We thought very thoroughly about that – I think there is something optical. What she’s doing is asking us to look closely at the artwork. So it’s not about trying to have some kind of effect, she’s really saying, pay attention, think slowly, think carefully and really think about perception.

Gego: Line As Object runs at Henry Moore Institute, Leeds until 19th October 2014.

Images © Fundación Gego

Photos: Jerry Hardman-Jones