As someone who prefers my art nailed to a wall in a gilt frame behind a wire barrier with a DO NOT TOUCH sign, I wasn’t sure what to expect from the Compass Live Art Festival event I’d spotted over the weekend.

Where To Build The Walls That Protect Us promised an “opportunity to imagine a future Leeds” by wandering around with “selected experts” chosen to talk about 4 different themes: climate and terrain, industry and commerce, mobility and communications and buildings and the life between them.

I booked on them all.

The walks took us through the Dark Arches to the canal, along Kirkgate to the centre of town, down Water Lane to parts of Holbeck no sane person would be caught strolling after dark, and over Leeds Bridge to a marooned car park on the edge of Hunslet. There are prettier places for a promenade in the city. But pretty doesn’t necessarily have as interesting a story.

The walk to the canal highlighted the city’s relationship to the river it was originally built upon. As a city we have turned our back on the river but, as last Boxing Day showed, sometimes the river insists forcibly upon its presence. So we build walls.

I mentioned to Councillor Yeadon that there was a great documentary by Leeds’ great urban historian, Patrick Nuttgens, on Leeds as an inside out, back to front, wrong way round city, and his comments on the river are about 15 minutes 30 in… he’s not so prescient about transport, however. Just goes to show even the experts get it wrong.

Tom Forth’s walk took in the several iterations of the White Cloth Hall, and the radical alternative, Tom Paine’s Hall.

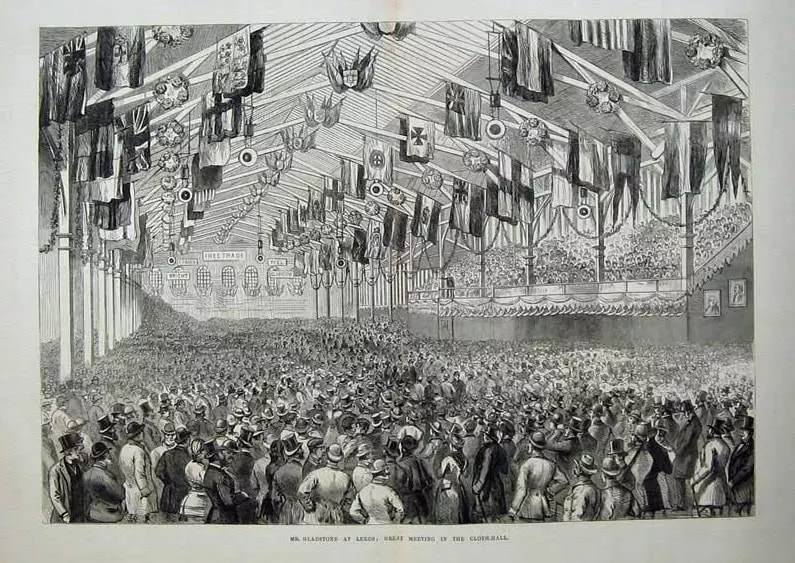

These were the equivalent of The Trinity Centre or Victoria Gate back then, with one major difference. The Victorians valued the political dimension of public space. These weren’t just spaces for commerce, retail and entertainment, they were genuine agoras, where public discussion thrived. I can’t imagine Jeremy Corbyn appearing to throngs assembled in John Lewis anytime soon.

Rob Greenland took us over to the Holbeck Viaduct, passing the Round Foundry and the site of Matthew Murray’s original engine factory. Oddly, as was pointed out, this is now an eerily quiet spot.

The last walk with architect Simon Baker took us out looking for zombie spaces and potential plots.

Potential plots are plentiful – they are everywhere you look

I can see the potential even here, and I know intuitively what’s wrong with the space, though I couldn’t say exactly how to unlock it – that would take the expertise of an architect or urban designer

The term “zombie space” triggered the only argument of the weekend. Simon, a practising architect, eschewed all notions of expertise (he claimed to have proudly contributed a chapter to a book decrying the very notion) and then began his walk by reading from several academic papers detailing the concept of “zombie space.” We were standing in the newly opened Sovereign Square.

“This” said Simon, gesturing towards the trim lawn and neat slatted seating, “this is what I mean by zombie space.”

One of the non-expert punters piped up. He said he liked the space. He could imagine working in one of the surrounding offices and would enjoy looking down on the greenery. It was nice. Pleasant. He felt good about the place. It made him happy. Zombies don’t.

Simon, being an expert in inexpertise, disagreed with this particular expression of ignorance, and reeled off a list of why the space did not work objectively (he used the word “greenwash” which I’m still trying to fathom.)

(Obviously zombies destroyed this bollard.)

Personally, the space doesn’t do much for me. But I can’t say I’m convinced it’s zombieish. Neat, tidy, presentable, well-mannered, eager to make a good impression… it’s more of a Mormon space. A bit too nice, too courteous, over-attentive, so much that you don’t really want to spend any time in its company. It hasn’t converted me and never would. But it’s certainly no zombie. I avoid places like this not because they may want to devour my living flesh but because they sap my will to live. They are urban candy floss.

(I know I am being mean about Mormons. In reality I admire how much time they spend just hanging out with the despised and derelict in my local crappy park without much hope of getting anything out of it… but I also know that Mormons have a sense of humour and don’t tend to righteous rage, so I’m pretty safe taking the piss. They are used to it.)

All the walks began in Sovereign Square.

This is how it used to be.

Dirty, dilapidated, dangerous… but full of life! The sort of place that swung a baseball bat and stuck two fingers up at oncoming zombies.

The one thing that keeps on coming back to me after a weekend spent with Where To Build The Walls That Protect Us is imagining a future where we could keep places such as the Queen’s Hall. I’m sure the Cafe Nero is lovely but it doesn’t really do it for me.

Zombie coffee anyone?

I was vaguely interested in attending these walks although following some of the leaders on Twitter I knew pretty much what I was likely to get: from Cllr Yeadon, flood defences and the importance of climate change; from Tom Forth, how the make money from data; from Robin Greenland, pedalling the city and building communities and from architect Simon Baker, who describes himself as a “designer and creative leader … passionate about producing meaningful work by galvanising his team to deliver better places to live and work”, no doubt some tosh about human qualities in urban design and the user experience.

So, at the outset, this looked a little like a young fogies’ version of the Civic Trust supper walks but without the supper.

The title was a bit worrying too “walls to protect us” – personally I think the city is pretty well or even over “protected” already. Who or what exactly do “we” need to be protected from? I won’t answer that.

Finally, the billed opportunity to sit in a shipping container with a load of play equipment putting my reflections for the future of Leeds into model form for the benefit of Cllr. Yeadon was just too much to contemplate. So I stayed in.

Sure enough, Phil’s description of the actual walks induced a further shudder: “Agoras where public discussion thrived” -really? “The back to front city” – oh dear me. “Zombie spaces” who dreamed that one up?

And, at the end of the day, despite Phil’s more critical tone and conclusion, his report conveyed my worst fears that as a cultural event this was more exercise in recycling existing clichés than discovering anything very novel, unusual or “exciting” and had the added potential to degenerate into another waste of time exercise in public engagement.

No there has got more to the city than this. Rather than always looking at the built environment as the city you can see and interact with how about a look at the city that you can’t see and you are not encouraged to interact with?

Using the clichéd analogy of the city as a body, some of its hidden parts and processes can be uncovered. Thus, the city sustains itself through systems for the circulation of energy, food, data and people. It city senses itself through security and environmental monitoring. It protects itself through various legal jurisdictions, policing powers, and resilience plans. It digests its effluent through sewers, recycling and landfill. The desiring city seeks sexual pleasures and the delights of consumption and entertainment. The city grows through its expanding real estate driven by the hidden hands of investors now increasingly drawn from overseas.

Of course, we are lead to believe that even in this time of austerity everything is working more or less as normal with a few residual issues still to be addressed but above all the compassionate and competitive city is open for business. But clearly this is at best an oversimplification and I would argue it is through an examination of the workings of the invisible city that we can find more about what is going on.

There are many sites, locations and points at which the hidden city becomes visible: in the cabling and wiring beneath the streets, in the rubbish bins outside supermarkets, on the late- night buses and trains (such as they are), in the CCTV masts and air monitoring stations, in the uniforms of the various city wardens and private security officers, in effluent outflow pipes and sewerage farms, in the licenses afforded to bars and clubs and in the windows of commercial estate agents and in the property pages of the Yorkshire Post.

All these aspects have a past present and future which might be open to imaginative cultural entrepreneurs to interpret, curate or facilitate (sorry to use the jargon).

Let’s try to do better than wandering around the city centre with the usual suspects coming to the expected conclusions.