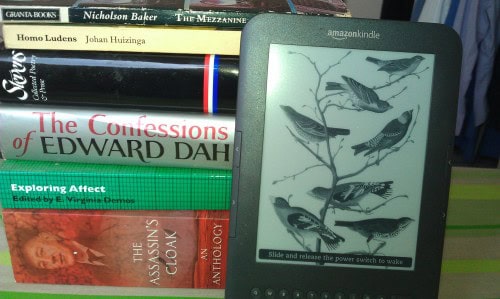

I am filling my kindle with ebooks. Yes, I am. Already I have downloaded over 300 volumes (about 10% of the capacity if Amazon is to be believed) more than enough to experience the mild exhaustion of exponential choice. If you happened to snatch my Kindle from my cold dead hands (let’s face it, you’re not gonna get your greasy mits on it otherwise) you’d notice how orderly, how tidy, how thoroughly sensible and sorted my virtual shelves are. Ludicrously so. There’s immense pleasure to be had inventing lists and categories, playfully sifting, shifting, combining books in ways that would never occur in the more restrictive economy of analogue print.

In fact this fastidious neatness in profusion is in complete contradistinction to my serious collecting practice. Every room in my flat, every ledge, every vacant space is freighted with tottering towers of books. The primary principle of organisation here is chronological; the newest purchase placed on top of the nearest pile. When that pile finally collapses – and why exactly do vertically arranged books bow spinewards? there must be some physical law operating to determine the terminal height of a stack of paperbacks – the secondary principle takes over, and I construct a pile according to equivalent size and shape. This is certainly my habit if not my preference exactly.

It would be presumptuous of me if, in order to appear well-informed and culturally astute, I weighed in on any one side into the debate over the authenticity of print versus the digitised future – though I don’t believe the ebook necessarily spells the end for the bricks and mortar bookshop (for instance, Borders collapsed because of bloody stupid business practises, not because people don’t want paperbacks.) And I am not getting into any argument over Digital Rights Management (DRM.) There is no argument; DRM is idiotic. Nothing on my Kindle is DRM’d. Never will be. What I’m most concerned with here is to shed some light on the relationship of the Kindler to his downloaded library, the act of collecting rather than the collection.

The Kindle eradicates any trace of romantic aura from acquiring a book. Most of the analogue books I’ve bought have binding associations with a particular place or time or person. Beside me on the top of the nearest book pile is a paperback copy of Robert Graves and Alan Hodges, “The Reader Over Your Shoulder,” a 1979 reprint of the original 1947 edition. I bought it in a shabby, sour smelling, second hand shop on a rainy Saturday in Bridlington, where I had retreated to avoid a bus load of day centre clients we’d taken for an outing to the coast. They had scattered to investigate the charity shops and invade the penny arcades. I was huddled under an umbrella trying to give the impression of casual intellectuality to a woman with whom I was desperately trying not to become romantically entwined, who in any case seemed more interested in the picturesque postcards than my pretensions. I’d been given the original hardback copy by my Sixth Form English teacher as a parting gesture when I left for university. It was from his own collection. The spine was loose and stringy and there were scribbles in the margins in the spidery pencil he always used to mark any absurdity or infelicity of language that provoked him. Many things provoked him. Seemingly even his hero, Robert Graves. Unfortunately the book had been left behind in one of my many moonlight flits. The paperback, though in perfect condition, could not replace the original gift, which had not only been read, it had been worked over, worried at and wrecked. It had been used. The Kindle cannot compare and has no compensatory feature for that kind of benefit.

The Kindler experiences no great inward shift of soul when acquiring an ebook. Conversely, there is no great eruption of angst upon losing, deleting, or otherwise having ones possession rescinded. A while ago I calculated that I had collected almost 20,000 books over the course of my life. I have sold a good 5,000. Another 5,000 odd were lost in an incident involving a skip and an angry in-law (fortunately said in-law was too tight to splash out on a three-for-two skip deal else I’d have been totally wiped out!) More recently a couple of hundred fell victim to an act of nature and a flaw in my sister’s roof slates (how hard it is to insure books, by the way!) And, as I mentioned earlier, countless precious volumes have been left behind during my regular escapes from the clutches of brutish, belligerent landlords (as a class, I have found landlords to be no great bibliophiles.)

Each and every one of those books that I can no longer call my own was individually mourned; its loss was a matter of deep and sincere regret. I cannot say the same about the Kindle. Politics and legalities aside, even if Amazon were to decide that my copy of Fahrenheit 451 was a dud and decreed it “disappeared” overnight, the news would cause me a slight twinge of chagrin but no great distress. I would simply download another copy. That’s part of the fun, isn’t it? Getting miffed about such a minor infringement of property rights seems about as sensible to me as complaining that Apple sneaks into your PC when you’re not expecting it and updates your iTunes software. Even if I dropped my Kindle into the bath and the whole thing got trashed it wouldn’t matter to me too much; all my downloaded books are backed up several times, I’d simply lose the time it took to transfer them onto a new machine. And the machine itself cost less than my last library fine! Not that dropping the thing in water would have any effect anyway; I just pop it in a Ziplock bag and I can read Plato in a power shower, no problem. My enjoyment of ebooks is much more secure than any print book could ever be.

Thus there is in the experience of the Kindler a dialectical tension between the poles of playfulness and possession. It’s like being a kid again. When we were children we had a mysterious relationship to ownership. Our books were not ours; we had choices, often vast choices if we were fortunate, and we felt as if we’d never run out, as if the possibilities were inexhaustible, though a favourite few books went through countless repetitions and re-readings and many more books were left unopened. We had no adequate notion of order back then and no concept of propriety. The way we shelved them, read them, tossed, lost, cut-out and coloured-in them would not have been acceptable in any grown up context. Mechanical copying never occurred to us – we just didn’t have the means – but we felt free to mimic, to make, to imagine new books of our own. We played pretend with books long before we possessed any, before even we had the idea that they must be shared. Play is prior. Before books had exchange value we made them special objects (special in Ellen Dissanayake’s sense) and our relationship to them was immediate, engrossing, animated. We were captivated. It’s how we learned to build a world inside our head and call it fiction. It’s probably how we learned to lie, by kidding ourselves. In the magic circle of childhood reading there is only room for one reader.

The Kindle returns us to this repressed solipsistic experience of the book. Infantilizing or invigorating? Either way, adults don’t approve. Totally self-referential, more concerned with play than possession, whimsical order than established categories, the Kindle brings out the child in us. I have to admit that I have not read more than a couple of items on the thing since I got it; I have however spent hours changing the front covers of every book I have downloaded, and days scouring the web for obscure items of minor literature which I can pinch and add to my collection. I have even, just to pass the time, visited the Kindle store . . . but why shop at the chains when the independents are so much more interesting? So, if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to find a PDF of Bonamy Dobree’s “English Prose Style” and anything I can grab of Edgell Rickword’s critical essays. If anyone knows where I might find them, don’t point it out! The fun is in the chase.

When I was a lad I used to hunt round record fairs for crappy 4th generation vinyl copies of Prince rarities and bootlegs. These fairs, I guess, were the equivlent of the sour smelling bookshop in Brid. Although a goodly number happened down the coast at the Grand Hotel in Scarborough.

Ten years later, when I discovered Napster I downloaded the complete works of Prince (to date). 9 gig of brilliance and shite in unequal measure, I’m sure.

I say I’m sure, because I never listened to the damn stuff. What I learned at that point was that limited finances and resources are a great asset when it comes to the appreciation of Art.

It does not surprise me in the least that little has been read on the kindle thus far. Because nothing really gets read in an infinite library. Beyond book spines and blurbs. The thrill of the chase is emptied of all meaning when the quarry does not exist. You can dress this up in this season’s Absurdist t-shirt, but it acquires no more meaning in the process. And when the chase is only a search engine away, you may as well surf online dating sites.

Celebrating the loss of attachment may sound to some like Zen perfection. For me, object relations are not to be sniffed at. Even if that keeps my nose pressed up against glass of real enlightenment.

I too am surprised by my lack of love for the kindle, and all its works. It’s tooth rotting methadone, compared to the infinitely superior opium of a real tome.

The “real tome?” You’ve got one of those, have you? There’s this teacher I once had, did this routine with Palgraves Golden Treasury . ..

But seriously, and stepping back from my role as Beeston’s answer to Walter Benjamin, maybe it’s a good thing to snap super-annuated attachments and get over our relationship to a shelf load of objects? I have far too many books and no place to keep them; they are a burden on other people. But, like the narcotic addict in your revealing image, I keep on craving my next fix of pain numbing fiction. I bought two more hardbacks this week – from the damned PoundShop ffs! The floorboards of my flat are buckling. If there was a fire I wouldn’t be able to get to the door for remaindered reading matter. The place would smoulder for months and my carbon footprint would be positively obscene . . . surely, you’d allow me to use the Kindle as some kind of transitional object?

This week the Kindle has been useful. I’ve spent a lot of time waiting around in bleak, soul-crushing, spirit-extinguishing, sense-depriving offices; surely reading Sir Thomas Browne as I wait my turn at the CAB is preferable to scrabbling my brain with Sudoku? Or, indeed, reading Harry Potter?