The Life and Times of an African Caribbean British Man: The Authorised Biography of Arthur France MBE

Review by Liz Kitching, Leeds Stand Up To Racism

We are in the era of Black Lives Matter (BLM). And in the year that marks 75 years since the arrival in 1948 of The Empire Windrush bringing the first post-war immigrants from The Caribbean; which would later in 2018, reveal the scandal that thousands of British citizens had been detained, deported and denied documentation, benefits, education, housing, work and health care. Further scandalous since Human Rights Watch recently reported that many still have not received their rightful compensation and many of those citizens died before they could receive theirs. It is also the year that marks 30 years since the murder by a gang of racist men of Black teenager Stephen Lawrence and his father Neville writing in The Guardian on 22 April 2023 says that any progress around Racism has been reversed under 13 years of this Conservative Government. In August this year it will be 30 years since Joy Gardener died following an immigration raid in which she was hand-cuffed, bound and gagged by Home Office officials. Tory MP for Dorset, Richard Drax who owns large swathes of Yorkshire and Dorset land still owns a plantation in Barbados and this is part of the “reparations” campaign going on today.

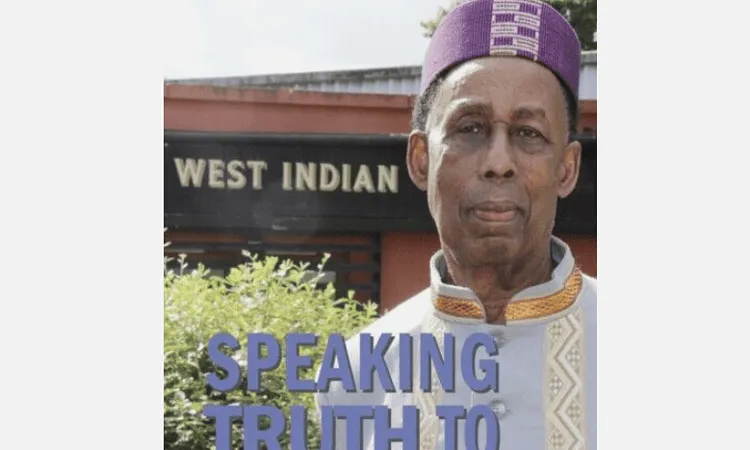

It feels very hopeful then to read all about the life of Arthur France, now 88 years old, and whose achievements are many, varied and wonderful for someone who arrived to the UK in the 1960s to face life under a racist system. Max Farrar provides a brilliant account of this extraordinary life.

Arthur was political from a young age in Nevis as his relatives there were part of the Labour Party and were always engaged in the struggle against the White colonial oppressors. He continued to be politically radical (and still does) during his years in Leeds.

He is especially famous for bringing to us the first Carribean Carnival in Europe – “Leeds West Indian Carnival” and it was in 1967 and made Chapeltown and Harheills famous . He wasn’t alone of course and in the book you will meet his contemporaries who worked and struggled with him to make it all happen. Chapter 8 – Emanciption: Making Carnival – is one of the most rich in detail end exciting things you will ever read. Preparation for Carnival goes on all year round. For Arthur, Carnival represents the struggle for emancipation as he remembered those celebrations from his youth in Nevis. With African roots, “masquerade” is explained along with each individual story of every costume and every queen and every float produced for the annual parade. The streets of Chapeltown and Harehills and Potternewton Park are alive with colour, music, drums, food and celebration for the long weekend at the end of August every year. For many of us this represents an opportunity for defiance and resistance as well as a good party.

Arthur and his friends and colleagues also gave us The West Indian Centre – a social club used by many thousands of people all year round and another marker on the Chapeltown map.

Chapter 4 – It’s all about Education – stands out for me. All anti-racists know too well how Black children were and still are terribly let down by the education system in this country. This matter was also a strong feature of the fantastic Small Axe BBC tv series by Steve McQueen . See also “The Mangrove Trial”. In 1971 Arthur and his associates of the recently formed United Carribean Association set up The Saturday Supplementary School for Black children in Chapeltown. With committed Black and Asian teachers the school ran for five years and resulted in the local authority recognising the importance of the presence of Black and Asian Teachers and leaders in mainstream education. It also produced a generation of confident young people who would go on to stand up for themselves in a racist society and in the face of police harassment and brutality. Arthur himself often stood up to the police during the 1970s and 1980s giving Black youth the confidence to claim their own streets.

Arthur saw himself as part of the Black Power movement and a Black Radical. His influences from C.L.R. James (Recently awarded a “Blue Plaque” ) and Darcus Howe to Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Junior are discussed throughout the book. Anyone engaged in anti-racist campaigning and struggle will be familiar with these names and with David Olusoga, Afua Hirsch, Linton Kwesi-Johnson, Benjamin Zephania and Caryl Phillips and they all feature here. Max Farrar, Arthur and others are leaders in the campaign to have the story told of David Oluwale – The David Oluwale Memorial Association (DOMA). David, from Nigeria was killed in 1969 by two police officers – Kellerman and Kitching following years of police brutality and harassment. As a result, David now has a “Blue Plaque” and The David Oluwale Bridge in the centre of Leeds. My favourite writing about David Oluwale is that of Professor Caryl Phillips in his chapter Northern Lights in his 2007 book Foreigners.

To conclude I would draw readers’ attention to the many other achievements in Chapeltown as a result of Arthur’s work, struggle and influence. Solicitors of the Chapeltown Law Centre were instrumental in securing the release from police custody of Black youths who had been arrested, sometimes violently, for no good reason. A film on YouTube by Dr. Clifford Scott – “Chapeltown, a case study on the limits of collective violence during the 2011 riots” – tells the fascinating account of the efforts of Lutel James of the Chapeltown Youth Development Centre and Claud Hendrickson who persuaded West Yorkshire Police to stay away from the streets during the disturbances of that time. The police were in preparation with vans, cars, riot shields and dogs. There was no riot in Chapeltown that summer as there had been in London and other cities following the fatal shooting of Mark Duggan by the police. Thank you, Arthur France.