Leeds International Festival 2019, 2-12 May, various venues around Leeds.

Leeds International Festival is coming soon and the programme is making PHIL KIRBY think.

I was chuffed to find Armley mentioned in the introduction to the programme for Leeds International Festival 2019; “events and activities will be popping up all around the city at important cultural venues in areas such as Hyde Park and Armley,” wrote the Festival Executive.

The important cultural venue in Hyde Park could have been one of several (it’s the Picture House, the one we all know and love.) But Armley? I live in Armley and have to admit I was scratching my head to place where it could be. Mike’s Carpets, maybe? Certainly a cultural landmark, and the most iconic space in LS12. It used to be the second best known building in West Leeds until the gay sauna just around the corner burned down a couple of years ago; said to be the biggest and best attended gay sauna in the country outside London, the building was once the training complex of the British Open medal winning squash team in the ‘70s – anyone remember Jonah Barrington?

Finally I twigged. Interplay, obviously. The “Sensory Theatre” on Armley Ridge Road. If you don’t know what a sensory theatre is have a look at their website and book a place to see Conductor the show they are staging for LIF19. Not your average sit down, be quiet, and watch appreciatively kind of audience experience. Is there even an audience? Definitely an experience. Forget the standing ovation, you’re already up on your feet for this one.

There’s a map at the back of the programme. This might be useful, I thought, as Armley is not your standard, everyday, familiar cultural destination. I looked for Interplay. It certainly appears on the key to the venues, on page 70 – Number 11, Interplay Theatre, Armley Ridge Road, Leeds LS12 3LE – but take a look at the printed map on the page opposite. There’s no red dot locating Interplay… Culture in Armley is still literally not on the map.

This has something to do with the fact that Armley Ridge Road is a couple of miles West of the city centre. A map that accommodated Interplay would have to stretch way over the next page, and maybe a tad more. But it also reflects that culture in Leeds is still seen as predominantly something that makes a big splash in the centre and flows to the North, with a little cultural spillage to the South (well, Southbank, where the developments are.) One simple way to counter this prejudice would be to spin the the map 90% and make the page align West down to East? That way, Number 11, Interplay, would have managed to get it’s own red dot.

Just a suggestion. Anyway, forget the map. It’s a 15 minute bus ride. Catch the Number 16 from Wellington Street, get off just after the shops on Town Street, and Interplay is a minute’s walk away. Worth exploring. Happy to ride shotgun with anyone who fancies venturing into the wild West to enjoy some none city centre culture during the festival. Just give me a shout.

Minor quibble over, the Leeds International Festival 2019 is genuinely exciting, and like it says in the introduction, “offers something for everyone.” Flipping through the programme really does bear that claim out. There’s everything from an interactive game show where you get to play a special agent trying to save the city (from what you’ll have to find out), a data summit, an immersive art installation/music piece, a conference of front end developers (this one’s perhaps not for me, I wouldn’t know one end from the other), a day of talks discussing “How do brands achieve agile long-termism?” (not a question I’ve ever considered up til now, but sounds interesting), a forum about food justice and digital arts, a panel discussion about the scourge of acid throwing attacks featuring the Bradford doctor who invented the world’s first acid proof make-up (what a world we live in where that is even a thing!), a conference about technology’s impact on sports, a night of sex positive spoken word performances (now that’s my kind of thing), and Frank Bruno… and that’s not even half of it.

For the more cerebral amongst us there’s a series of talks around “What does it mean to be human?” curated by Chris Hudson from Leeds Beckett University. There’s a stellar bunch of speakers, and this is the event I think I’m most looking forward to. It’ll make you think, I think.

Professor Alice Roberts is talking about recent developments in our understanding of human origins – and if you’ve been keeping up with the news in the popular science press even over the last month or two there’s been a load of fascinating discoveries about our ancestors, the Denisovans. The New Scientist recently claimed genetic studies show they may have been interbreeding with modern humans as recently as 15000 years ago. I’m hoping to get an explanation of what it all means. Did they discover really Australia? Did they ever make it to Yorkshire? And why were they producing such incredible art? (Worth Googling Denisovan art, it is amazing.)

Simon Anholt is talking about “How good should a country be?” I think this is basically about how we shift from being a GDP as Gross Domestic Product country, to one more about Good Done to People. He argues that world leaders aren’t just responsible for their own population, they’re responsible for the whole of humanity and the planet we share. I’d absolutely agree. But there’s one question… how the hell do we get rid of the absolute shower of witless wonders we are lumbered with right now, and where do we find the leaders who get what the job is? What can we do about that?

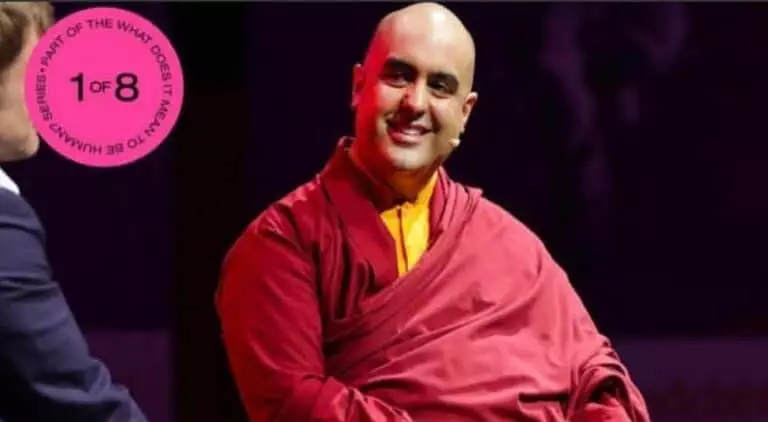

Gelong Thubten’s talk is “Staying human in a busy world.” He’s a Buddhist monk who contributed to Ruby Wax’s last book, How To Be Human: The Manual. I managed to have a chat with him on the phone last week (who says I never do research!) and asked him about mindfulness meditation, and what the benefits were. It seems to have come a long way since I dabbled in the dharma in my mid-teens. Back then it was taught in shabby, damp rooms in a neglected university building by men with beards and knitted tank tops who wanted to be Allen Ginsberg. Their version of meditation was a whack-a-mole of the mind. When a random thought popped its head up you had to bash it sharply with your mental mallet and square yourself manfully for the next intrusion of conceptual vermin. It seemed quite vicious, a scorched earth policy of the mind. And I didn’t like the zennier-than-thou vibe of the whole experience. My meditation practice didn’t last the summer. Thubten’s techniques are much gentler and easier on the mind – and he’s got much better dress sense.

He says you can’t get rid of your pesky thoughts anyway, so no point being so aggressive. Meditation is not cognitive pest control. And mindfulness is not a mental Rentokill. As he says in the book,

Mindfulness isn’t just the absence of negative thoughts, it’s about finding a completely different relationship to thoughts, positive and negative. Whatever you are thinking, the aim is just to notice the thoughts without judging them, and then they don’t have so much power over us. The point of learning mindfulness is to reduce suffering; and the reason we suffer is because we believe our thoughts and therefore we’re constantly being pulled into distressing mind states.

One question I asked when we chatted was about whether mindfulness could (or should) be taught to people to help them cope with jobs that are objectively abhorrent. The example I offered was moderators for social media platforms who have to witness the most despicable, violent and obscene behaviours for hours on end, so we don’t have to. Thubten said indeed it should, and he actually did mindfulness training with people who perform those tasks: “someone has to do that job,” he said, “it’s a bit like the police; not pleasant, but vital. And mindfulness can help them look after their mental health.”

I agreed, but the question still niggled. And I think I have come up with a harder case to answer; Devi Lal from Delhi, India, who was declared in 2012 to have the worst job in the world. He’s a sewage pipe driver. In the more overpopulated parts of Delhi the sewage system is overburdened and often blocks up. Devi is paid £3.50 a day (plus a bottle of bootleg booze) to spend his working hours submerged in human waste clearing the blockages dressed only in his underpants. During a six month period alone it was estimated that sixty sewage workers like Devi were killed on the job. Wouldn’t it be reasonable to assume the reason Devi and his co-workers suffer is not because of what’s going on in their heads. It’s because they’re neck deep in shit. And paid shit. I wonder if Devi would consider exchanging his bottle of grog for a mindfulness lesson?

Mindfulness has plenty going for it, I don’t deny, and I can see why it’s a hit with tech workers who spend their days in front of a nice clean screen and are paid decently for their troubles. But if you are paddling in poop it might not be the first thing you want. A trades union might be more productive, perhaps.

The last speaker at this event is Matt Haig, author of the non-fiction best seller, Notes on a Nervous Planet. His book asks a simple question:

How can we live in a mad world without ourselves going mad?

Many of us don’t. A 2014 article in the British Journal of Psychiatry claimed that the 2008 recession directly caused an additional 10,000 suicides. Additional!

“The aim of this book isn’t to say that everything is a disaster and we’re all screwed, because we already have Twitter for that,” he jokes; nonetheless he is convinced that austerity, alienation and anxiety, combined with the increasing pace of change, is doing incalculable damage to our mental health. And “the disorder isn’t individual”, he argues. “It is social. It is global.”

The basic question to ask of the modern world is what sort of human beings it produces. “We live in a 24-hour society but not in 24-hour bodies,” he says. We are over-stimulated and under-rested. We are constantly connected yet lonelier than ever. We work far to much, produce far too many useless, pointless, worthless products, then have to use “fear, uncertainty and doubt,” to sell them. And the work we do is mostly “bullshit jobs”, to use anthropologist David Graeber’s term.

“Employment is becoming a dehumanising process, as if humans existed to serve work, rather than work to serve humans,” he writes. (Though, compared to a Delhi sewage worker…)

Matt’s solution? Don’t give in to the robots. Assert your humanity. Emphasise our waywardness and difference. “Everything we need is here right now. Everything we are is enough.” A good message and a really good book. I’m really looking forward to hearing Matt speak.

While I was writing this (inevitably distracted by social media, with my mind elsewhere and my awareness just a bleary, weary blankness) I came across a news article about a robot monk in a monastery in Japan. The ancient monastery in Kyoto is apparently trying to attract young people by offering Buddhist wisdom dispensed by a life-sized android with a video camera in it’s left eye to help it maintain eye contact. The robot is based on a Buddhist deity, Kannon, who is Lord of Compassion and Mercy. She can also appear in female form too, so is truly an androgynous android.

Seems even mindfulness can be reduced to an algorithm, and compassion will be automated. Even a monk’s job isn’t safe anymore.

I’m hoping Leeds International Festival can help me think this stuff through. As it says in the introduction,

At a time when the future seems uncertain and we are bombarded with reasons to be downbeat, a festival of new ideas and innovation gives us a chance to step outside of the everyday and explore the brighter side of tomorrow.

Leeds International Festival, 2-12 May, various venues in Leeds (including Armley!)