What books influenced you the most? PHIL KIRBY raids his shelves for an oddly influential investigative satirist…

Earlier this week The CV was invited to speak to the Journalism Club at Leeds Beckett University. As always my colleague and co-editor, Neil, was a consummate professional and had prepared some notes and packed a bag full of props – books he thought would be useful to post-graduate MSc Journalism students – whereas I, as usual, merely managed to be wearing matching socks.

Half the books Neil passed around I’d personally have taken to the council recycling dump (obviously I would never do that! Always give away your unwanted books, you never know who may find them useful – unless it’s Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand, you are allowed to compost any copies of that you can find, that’s actually the law..) But we absolutely agreed on the book he chose as an example of a writer who’s inspired, influenced and occasionally infuriated us into setting pen to paper, Geoff Dyer’s But Beautiful. Anything by Geoff Dyer is worth reading, even this

Which got me thinking about which book I would have taken along. If I’d actually thought to plan ahead.

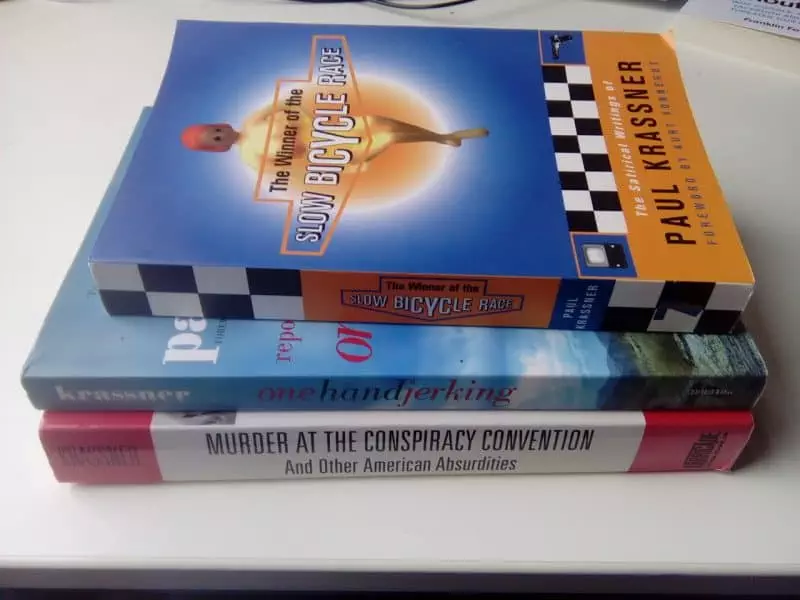

Looking at my bookshelves – ahem, mostly just book piles – I could have gone with any of my literary heroes; A J Liebling, Joan Didion, Joseph Mitchell, Susan Sontag, Murray Kempton, Dorothy Parker, Gay Talese, Elizabeth Hardwick. Tom Wolfe, Camille Paglia, Gore Vidal. But the writer I’d probably have chosen would have been Paul Krassner. Not the best known I imagine, but one of the most influential, and in ways that would get him in trouble with Journalism Club.

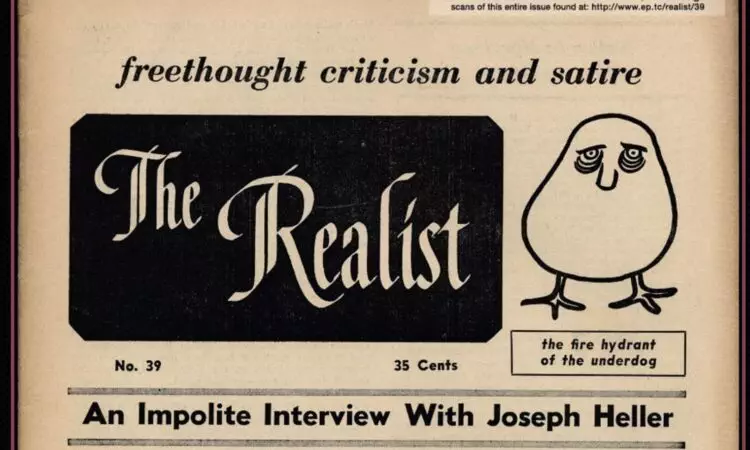

In the late 1950s Krassner set up an independent publication The Realist as an antidote to the frauds and hypocrisies he saw in the society around him. Both he and his magazine soon became a vital inspiration for, influence on, and participant in the countercultural revolution of the 1960s. The magazine was often uncompromisingly offensive, scathingly vulgar and deliberately controversial. Black humour, crafty hoaxes, and skilfully falsified information were weapons subverting the authority and influence of mainstream media. Anything to stick it to The Man.

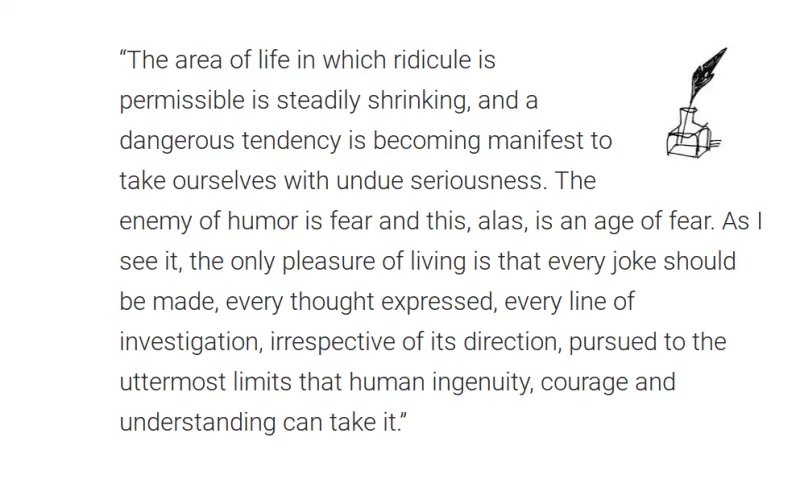

Krassner claimed inspiration for his stance of militant mirth from an article he’d read in Esquire by Malcolm Muggeridge, former editor of Punch, the British humour magazine. It still bears reading.

The piece went on to say, “By its nature humour is anarchistic, and it may well be that those who seek to suppress or limit laughter are more dangerous than all the subversive conspiracies which the FBI ever has or ever will uncover. Laughter, in fact, is the most effective of all subversive conspiracies, and it operates on our side.”

From the start, The Realist was fearless and reckless, printing material no other publication would touch. It dealt with free speech, abortion rights, women’s equality, the anti-war movements and psychedelics long before the mainstream caught up with such issues. Every major countercultural icon from authors Norman Mailer, Joseph Heller, Terry Southern, Ken Kesey, Robert Anton Wilson and Kurt Vonnegut, to comedians Woody Allen, Dick Gregory, Mort Sahl, and Lenny Bruce, featured in its pages. Mae Brussell was a regular too. She broke the Watergate story two years before the Washington Post.

Krassner financed The Realist through his freelance income, mostly as a writer and performer. Uncompromisingly independent, he never accepted ads or conducted marketing surveys, on the grounds that he might be influenced about what he printed. The only common denominator he saw among the magazine’s audience is “an irreverence for all the pious bullshit that surrounds us.” The Realist was originally subtitled An Angry Young Magazine, but over the years it used many tag lines, including The Truth Is Silly Putty, The Magazine of the Lunatic Fringe, and my favourite, The Fire Hydrant of the Underdog.

Krassner’s most notorious hoax was the cover story of the May 1967 issue, “The Parts that Were Left Out of the Kennedy Book.” The Death of a President, written by the historian William Manchester with the Kennedy family’s say so, was in the news at the time as Jacqueline Kennedy was demanding that the publisher delete whole sections of the as yet unpublished book. Failing to obtain the missing offensive material, Krassner, in his role of investigative satirist, decided to simply make it up.

He imitated Manchester’s style and elaborated urban myths, such as that Jackie had told the writer Gore Vidal she’d witnessed Lyndon Johnson leaning over JFK’s casket, chuckling. In Krassner’s version, she watches him moving rhythmically while crouched over the corpse.

Krassner believed the ultimate target of satire should be its audience, and included an editor’s note requesting readers include their zip code when cancelling their subscriptions. Many readers found themselves revolted by Johnson’s “neck-rophilia.” Cancellations poured in, with subscribers dutifully including their zip codes.

The White House did not respond; any denial would, in effect, be a concession that the incident was credible. As Krassner pointed out in a follow-up report, one of Johnson’s favorite jokes was about a popular Texas sheriff running for reelection whose opponents decide to spread a rumour that he fucks pigs: “We know he doesn’t, but let’s make the son of a bitch deny it.”

The article was intended as a metaphorical truth about LBJ’s crudity and lust for power, a hoax that fulfilled Picasso’s definition of art as “the lie that makes people see the truth.”. But there were many who accepted it literally, including people in high levels of the intelligence community who were in a position to know just what went on in the corridors of power. Daniel Ellsberg, who would eventually go on to release the Pentagon Papers, said, “maybe it was because I wanted to believe it so badly”.

Times have changed since Krassner was publishing The Realist and the sacred cows have all defected to the greener side of the political field. Irreverence is no longer on our side. Laughter, mockery and goading with lies have shifted allegiance.

Krassner was shocked to find this out for himself. He conducted the last published interview with right-wing publisher and provocateur, Andrew Breitbart, founder of Breitbart News. Breitbart is notorious for using fake news sites to source its dishonest and deceptive “journalism.” Andrew Breitbart claimed that Krassner’s example had been a direct “inspiration”, and said he admired Krassner’s “trailblazing and causing mischief and mirth and effecting the type of political and social change you were attempting.”

History may or may not be on your side, but it looks like history does have the last laugh.

For the last few years of his life Paul Krassner worked on several collections of his works, wrote an autobiography and then decided to concentrate on novels, which he found challenging, even though he’d been making up material all his life. “But that was journalism,” he said.