Photo by David Lindsay

The fifth annual Northern Art Prize landed in Leeds Art Gallery last Friday. The twenty-strong longlist has been whittled down to a shortlist of the four artists on display. It’s just the right size and satisfyingly coherent.

The first room combines the works of Huddersfield-based Liadin Cooke and James Hugonin from Northumberland. Their work is startlingly different, Hugonin’s measured and meticulous methodology standing in stark contrast with the raw physicality of Cooke’s works.

The Hugonin works, hung on the far wall of the gallery as you enter, all look more or less the same from a distance. Each large canvas is painstakingly divided into a pencil grid, onto which a numeric colour system is transcribed before the final epic painting-by-numbers task is undertaken. Each takes the artist up to a year to complete.

Up close, the viewer is invited to consider the artist’s self-imposed discipline, deciphering his choices of colour placement and noting the surprising imperfection within individual marks. Moving back from the canvas, the colours begin to dance, emerging and shimmering into shape in brief moments before falling back into place. There’s a sweet spot at middle distance where suddenly the painting’s separate identities swim into view, a barely perceptible dominant colour and rhythm emerging from each.

Cooke’s works perhaps suffer a little from their placement alongside Hugonin’s paintings. With none of his precise attention to detail, their charms are of a much cruder variety. She delights, very apparently, in the texture of objects. This is nowhere more evident than in the large, striking clay sculpture which sits alluringly near the gallery doors. Painted and unfired, it bears the imprints of the artist’s fingers in a way which makes you want to plunge your own into the (presumably) still-soft clay. This sheer physical presence even extends to a distinctive paint smell which hangs in the air around the sculpture.

Moving through to the rear galleries, look out for Richard Riggs’ telegraph poles sculpture in the stairwell. Reaction to Riggs’ works in this show seem to have focussed on this piece: unfortunately I managed to completely miss it! Riggs plays with perceptions of familiar objects and forms: there’s something of the YBA school of recontextualisation within a gallery space to the chairs and desks pieces in the end room. For me, his most striking work is The fort was here before it was built, a cyanotype of a rope knot. An incredible depth of colour creates a 3D, almost holographic effect as the knot shape emerges from deep inky blue.

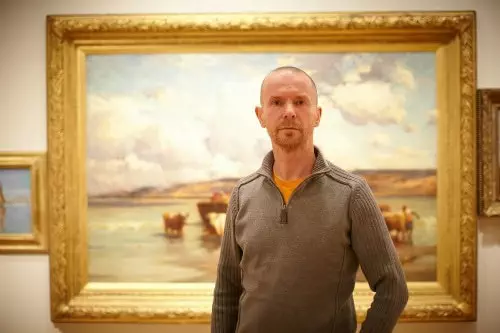

The final space is given to Leo Fitzmaurice. He’s installed two large-scale works in the gallery. Horizon (Leeds) is as simplistically clever in concept as it is delightful in execution. Fitzmaurice has taken around a dozen 18th and 19th century landscapes from the Gallery’s collections and hung them side by side to create one long landscape. He uses the ever-present landscape horizon as a thread introducing continuity between the distinct works. It’s a lovely concept, bringing forgotten works out from the storeroom and layering his own interpretation upon them, creating a new work that’s both respectful to, and more than the sum of, its constituent parts.

Fitzmaurice’s second work, The Way Things Appear, is a 60-slide projection housed in a temporary wooden structure. It’s a series of unpolished images taken from the artist’s mobile phone, which were never originally intended to be exhibited in their own right. Each shot contains something to make you smile: a visual pun, an unintended echoing of forms, a pair of Mickey Mouse ears formed from a serendipitous alignment of shadows.

The beauty in these images is in their amateurish quality: you or I could take the same pictures to the same quality, but we very probably wouldn’t notice the subject matter that makes them so interesting. The display allows us to see the world through the artist’s eye, spotting with him the patterns and details in the everyday subjects of the images. The format keeps things light-hearted, too. With each new images that flashes up, the viewer knows they have a few seconds to spot the joke before the slideshow moves on.

Overall it’s a varied show, successful in illustrating the wide range and quality of work being produced at this end of the country. The exhibition runs until February 19, with the winner being announced in mid January.