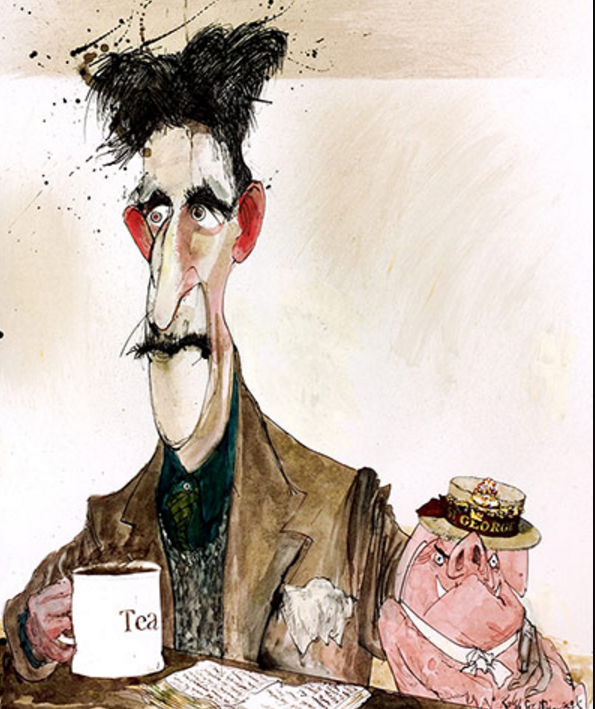

In Politics and the English Language, written over 70 years ago, George Orwell listed four “swindles and perversions” that make for bad writing.

The fourth, “meaningless words”, he said particularly bedevilled writing about culture.

Words like romantic, plastic, values, human, dead, sentimental, natural, vitality, as used in art criticism, are strictly meaningless, in the sense that they not only do not point to any discoverable object, but are hardly ever expected to do so by the reader. When one critic writes, ‘The outstanding feature of Mr. X’s work is its living quality’, while another writes, ‘The immediately striking thing about Mr. X’s work is its peculiar deadness’, the reader accepts this as a simple difference of opinion.

Substitute “bold, visionary, vibrant, iconic” for Orwell’s examples and he could be writing about Leeds right now.

Orwell argued that bad writing was bad thinking, and both reinforced the other

A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.

And he said the problem was “bad habits spread by imitation.”

He was optimistic enough to believe that bad habits could be avoided by taking the trouble to think clearly, and thinking clearly was the necessary first step towards … regeneration.

Anyone working for the council, interested in regeneration, and culture, might want to read a bit more Orwell.

He has a passage that could easily be talking about how we find a copywriter for the bid to become European Capital of Culture 2023

Modern writing at its worst does not consist in picking out words for the sake of their meaning and inventing images in order to make the meaning clearer. It consists in gumming together long strips of words which have already been set in order by someone else, and making the results presentable by sheer humbug. The attraction of this way of writing is that it is easy. It is easier — even quicker, once you have the habit.

His most salient point is about the use of second-hand words, production-line thoughts and battery-farmed imagery

By using stale metaphors, similes and idioms, you save much mental effort, at the cost of leaving your meaning vague, not only for your reader but for yourself. This is the significance of mixed metaphors. The sole aim of a metaphor is to call up a visual image. When these images clash … it can be taken as certain that the writer is not seeing a mental image of the objects he is naming; in other words he is not really thinking.

Orwell concludes his essay with a practical checklist of strategies for avoiding such mindless cranking out of thought and the rotten writing it produces

A scrupulous writer, in every sentence that he writes, will ask himself at least four questions, thus: What am I trying to say? What words will express it? What image or idiom will make it clearer? Is this image fresh enough to have an effect? And he will probably ask himself two more: Could I put it more shortly? Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly? But you are not obliged to go to all this trouble. You can shirk it by simply throwing your mind open and letting the ready made phrases come crowding in. They will construct your sentences for you — even think your thoughts for you, to certain extent — and at need they will perform the important service of partially concealing your meaning even yourself.

I hope whoever gets to write the bid for 2023 has read Orwell.

And I hope they Google a couple of things

Dundee vibrant

Dundee iconic

Dundee bold vision…

Talk about bad habits spread by imitation.

Hmm Phil you’re churning out so much stuff around the Cultural Strategy now I’m struggling to keep up.

So, pausing for breath I tried to sum what I thinking you are going on about and how I might explain what you are going on about.

Obviously as a litterateur you have a thing about language and writing so not surprisingly you point up the vacuity of the language of the Cultural Strategy and its alienating effects. In your most recent piece regarding Orwell you seem to be saying implying beyond bad writing and its associated bad thought there can perhaps be better writing based on or leading to and better thoughts.

Is there some kind of equation implied here that a better written and therefore better thought cultural strategy would produce a better cultural strategy? If so I would have some reservations about this.

First up on Orwell I must admit English Literature is not my thing – A Level Grade E in fact – so I have no idea where he sits in the canon now. Can you still read Animal Farm for GCSE? Is he much studied in Higher Education? Politically those on the Left celebrating the achievements of the Atlee Government would be interested in a re-read but no doubt would have their reservations. For the more contemporary Left – Zizek, Chomsky: Orwell – I doubt it.

On Orwell’s approach to language surely none but the ardent traditionalist (yourself?) can take this seriously after the revolution in thinking about language and meaning which went on in the eighties. Without being too pious here isn’t the more prevalent argument today that the relationship between language writing and meaning much more irrecoverably slippery than Orwell can allow and that the use of forms of language and writing are intrinsically embedded in systems of power.

OK so where does this lead us in a search for an understanding of what the language of the cultural strategy represents. Basically, I believe that the piece I got “Robin Goodlad” to put into to one of your previous articles gives a clue – this document is the output of the most recent “circulation” of elite power in the city and in this way your criticism that is demeaning, alienating, vacuous and arid in linguistic terms is entirely valid.

Let me briefly explain. In the years, I have lived in Leeds I would say there have been four moments at which the language of city politics has shifted – “Motorway city of the Seventies” “Say No to Whitehall Control”, “The Leeds Renaissance” and now “Best City” and the associated Cultural Strategy. I would argue without going into too much detail that each moment has been propelled along by specific elites who have each sought to exploit the power to justify their interest.

So crudely against your most recent argument there can be no better language or no better thought per se at any moment this judgement will be made depending on who you think the Angels are. Language and writing are functional within a wider political project.

So, let’s look briefly at these moments, their language and the elite they supported. “Motorway City” – I can’t do this exactly but what I can say is that co-existing with this era was slum clearance on a big scale which was based on the documents Older Housing in Leeds – the language form here legalistic, statistical, rationalistically scientistic promoted by the Environmental Health Department and Old Labour style council.

“Say No to Whitehall Control” this was basically New Left Labour Leeds resisting Thatcherism in the spirit of “Fight the Cuts” and having a Nuclear Free Zone and a Peace Centre in the Merrion. The language was florid and emotional see “Leeds After the Bomb”.

Next up, “Leeds Renaissance” – the best example of writing here is John Thorpe’s self- congratulatory coffee table offering by the City Council “From a Tile to a City” which gives and aesthetically orientated account of the rape of the city centre by opportunistic private sector developers. I would put Martin Wainwright’s appalling “Leeds: Shaping the City” in the same rubbish bin.

Finally, Best City and the Cultural Strategy: by now the Council based city elite has become completely exhausted by decades of cuts and political marginalisation. In its vulnerability, it can only create a spectacle of progress through having a cultural strategy managed by a new force of third sector and commercial providers. Not surprisingly despite the appeal in the documents to economic benefits and social improvements there is no strong evidence any of this will be truly “transformative” and we are left with empty words on the page.

This article was brought to you by North Leeds Nihilist Publications.

Churning! That’s fighting talk around ‘ere.

So, let’s start with where we agree. I think your point about there being no necessary connection between better writing and better thinking, therefore no clear strategic benefit, is hard to counter. I’ll have to search for evidence.

And most of the last part of your comment on the history of the language of civic policy I agree with. Though you do make me want to read Martin Wainwright’s book … if you hear anyone rummaging in your bins tonight don’t worry (just make sure you dump it in the green bin provided as per council policy on recyclable waste.)

But there’s a little bit in between these two arguments that I completely disagree with. And it’s an assertion which I think undermines your case.

You mention this “revolution in language and meaning” that supposedly took place in the ’80s (I’d argue that what you are referring to started considerably earlier, but that’s by the by.) And you state that there’s “a more prevalent argument today that the relationship between language writing and meaning is … irrecoverably slippery.”

You asked for proof about my “traditionalist” view of language. Where’s yours for this postmodernist drivel?

If language is so slippery how did this “prevalent argument” ever take hold. If language is just power why should we believe the “prevalent argument”? How can you personally rely on a rhetoric of “explanation”, “argument”, “understanding” and that final, revealing “empty words on a page” when you apparently consider these things just the structural groanings of the scaffolding of power/knowledge?

You are more Orwellian than you’d like to admit!

Btw, the two academics that Orwell criticises in his essay, Laski and Hogben, were the Zizek and Chomsky of their time… Orwell has lasted. When was the last time you heard anyone bring up Hogben’s view of language?

Brought to you by the Rhetorical Alliance of West Leeds…

RAWLs to you!

Oh No – this (hem, hem) “conversation” is turning into the biggest disaster since I accidentally crossed swords with a professor from one of the south of England’s lesser known universities.

he was advocating a “Return to Tawney” as a solution the problems of contemporary Britain and I failed to spot he was not being ironic.

Of course my first instinct was to give you a quick blast with some Baudrillard, follow that with fusillade of Foucault and a double barrel of Derrida and finally detonate you does of Deleuze.

But then I thought OMG this is turning out to be worse than an afternoon at the Leeds Salon, a sad evening at one of those Intellectual “cafes” or one of those inquisitional meetings of Leeds Soundings. It was clearly time to take a breath.

bye for now

Sour

I take it about as seriously as you… but it’s fun to take the piss.

Leeds Draft ‘Cultural Strategy’ & ECoC2023 Bid

I have a fundamental problem with the ECoC2023 Leeds Bid proposal and now also with the draft Culture Strategy, published on Twitter last week. There has been a significant triumph of presentation over content in the announcements of these programmes.

This communication is my way of avoiding the inevitable criticism of me not ‘joining-in’ with the way it is required that we respond to the draft Culture Strategy within six (now five weeks and counting) to the draft culture strategy. The views expressed are my own and not necessarily shared by the co-directors of LSDG CIC.

Regardless of my personal views I hope we can all agree that the quoted ‘Vision’, for Leeds to be nationally and internationally recognised as the ‘Best City to Live’ by 2030, (originally announced by LCC in 2011), needs to be revisited, reviewed and refreshed, in the context of the need to have a shared, inclusive dialogue in response to the draft ‘Culture Strategy’. There had been consultation leading up to the adoption of this vision but there is some doubt that this is an acknowledged and fully shared by the people of Leeds. It seems to sit on a shelf waiting to be referred to only when necessary. For the Leeds submission to ECoC2023 to succeed we need to show that there has been active, continuous and inclusive involvement of citizens beyond those interested or involved in ‘arts’ activities. This process could commence now, in time for the first submission this year, with further development throughout the period up to the final submission next year, followed by continued dialogue as part of the process over the coming years, up to 2023.

However, my immediate and fundamental problem with the proposed ECoC2023 programme is that it appears to be more an ‘Arts’ bid than a ‘Culture’ bid and the subsequently published draft ‘Culture Strategy’ is not a wholehearted strategy for ‘Culture’, it is more a strategy for the ‘Arts’ with a bit of Leeds culture added in. I can see, from a distance that to deliver the two major pieces of work more or less at the same time and effectively from a standing start may have caused some difficulty.

Our shared vision for the six year period leading up to ECoC2023 should be based on the ‘process’ being as important, if not more important, than the ‘end product’. The process, so far, has been focussed on the preparation of a wonderful programme of cultural events as an ‘end product’. Accepting it is important to enter any competition with a view to winning, in the context of this bid, Leeds should accept that, win or lose, we are, as a community, committed to continuing the process. We should also have a conversation and establish a consensus as to what we expect the potential benefits and outcomes to be in six years’ time. Perhaps there is a case here for a ‘Six Year Vision’?

The feedback from current and previous successful ECoC bids that have taken on the wider cultural remit in their process has shown that this has resulted in positive and, most importantly, tangible outcomes for the cities, not only culturally but also economically, socially and environmentally. The proposed programme should now become significantly more inclusive and focus on these other sectors that not only define the ‘culture’ of Leeds as a city but are sectors of critical importance to making Leeds a truly better city. In particular, more attention to achieving a consensus on the definition of ‘culture’ is required. If we do not fully understand the difference between art and culture and what separates them then we are starting from the wrong place.

Leeds must also show in the submission that there has been active and inclusive involvement of Leeds people beyond those interested or involved in ‘arts’ activities.

Our bid should not just be about our ‘heritage’ and what extra ‘arts’ events we plan to promote in 2023. The bid process should be more about our broader ‘vision’ for the ‘future’ of our city and what it is we want to gain from this six year process to ensure there is a really positive legacy for all the people of Leeds. We need to look back in 2024, after the programme of events, and be able to measure our successes over the previous six years against our shared vision. In simple terms, the development of our city needs to be a part of a cultural strategy based on our shared ‘City Vision’.

This will require a wider sharing of information, more frequent presentations, appropriate engagement activities and inclusive decision making at all levels. The use of social media, such as Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook, etc., although helpful, will not be sufficient. The time, money and resource at the disposal of LCC and the ECoC delivery team may not be available, so perhaps more open invitations to the many active community organisations, beyond the arts, no matter how small or ‘niche’, paired with a share of the major sponsor donations currently aimed solely at the arts events would facilitate this? The much needed, truly inclusive involvement from the ‘bottom-up’ and co-creation by way of effective public/private partnership working at all levels, is needed now to ensure the successful delivery of our shared vision, apart from the winning of ECoC2023.

The dialogue throughout the PR/Media programme for the already planned activities for ECoC2023 is essentially arts based. This strategy of concentrating on the arts is clearly requiring a massive investment but precedents show that just investing in art will not change anything that really matters in the development of the city of Leeds.

Not understanding the difference between art and culture is a damaging confusion that we need to sort out without delay.

I understand that there is a great deal of misunderstanding whenever there is a conversation about the difference between culture and art, they are often regarded by many as the same thing, especially, I find, in the world of artists, of all kinds. Culture and art is not the same thing.

Leeds culture is about our society, the nature and quality of our lives in the city. It is about all aspects of our life and activities. This does of course include, for some, the arts and so it follows that investment in the arts to deliver access and involvement for all is a very significant and good thing. Culture is however everything that we encounter in the environment in which we live, what we create in our physical space including the way we communicate, the way we grow, access, provide and prepare food, the creation of buildings, spaces and places and many, many more things. Investment in all these things would also be a very significant and good thing.

The brief synopsis in the draft Cultural Strategy of the current state of the City of Leeds titled; ‘It is 2017, and now is the time to act’, rightly raises some very important cultural issues. None of which, will be solved or changed simply by investing in a series of arts events. The issues you have mentioned that are facing Leeds; housing, population growth, inadequate transport, pollution, the poverty gap and others that you have not mentioned; urban regeneration, health provision, community politics, devolution, unemployment, investment in green infrastructure and many more, all require a Cultural Strategy to deliver our shared vision of ‘Best City to Live’.

It is indeed 2017. I couldn’t agree more with the sentiment that ‘now is the time to act’, but it seems to me that we need to agree a strategy that will actually address those facets of our culture that need to be changed now, so that we can then establish the tactics that will make the strategy succeed. In 2009 I made a similar observation and together with an amazing and growing collection of individuals who shared a commitment to making things happen set out to make things happen now, that contribute to our collective vision for the future of Leeds.

I acknowledge the belief that the draft strategy is designed to stimulate change and to respond to the challenges and opportunities that present themselves’. It may well do. I have re-read the draft introduction with all references to ‘culture’ replaced with reference to ‘art’ and it all starts to make sense and makes for excellent reading.

Based on a premise that we have prepared an excellent ‘Arts Strategy’ I believe we need to now prepare a distinct and significantly more important ‘Culture Strategy’. In doing this we have a great responsibility to young people in the city to deliver a relevant cultural strategy that they have shared in creating, therefore understand, relate to and believe in so that they see a future for themselves in Leeds. An encouragement for them to participate and invest in the city in whatever area of interest they may have.

David Lumb

Independent Urbanist

Leeds Sustainable Development Group

Community Interest Company