Local author Richard Smyth (@RSmythFreelance) finally reads his grandmother’s first novel, Strange Heritage, and wonders about how her achievement unconsciously influenced his life …

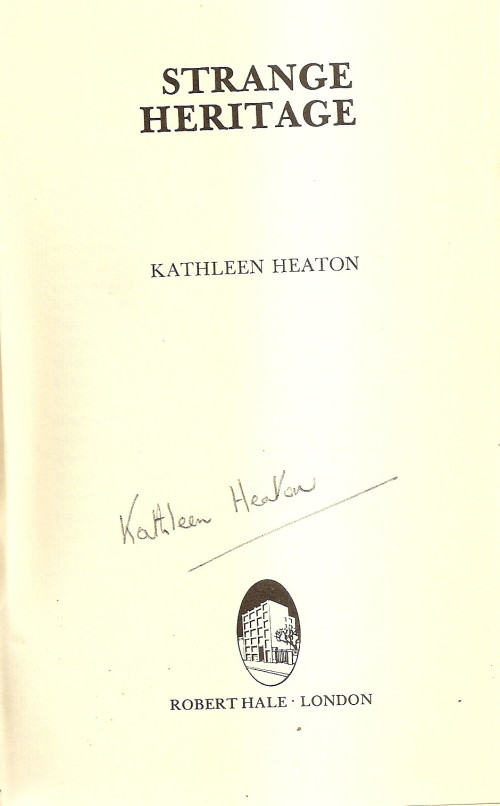

My granny’s first novel, Strange Heritage, was published in 1978, the year I was born. A hardback copy, with its ugly grey-and-green dustjacket, has been kicking around my parents’ house all my life.

I didn’t read it. It barely ever occurred to me to read it. I think it was one of those books on my parents’ bookshelves that I identified early on as a book that Wasn’t For Me, along with John Betjeman’s Summoned By Bells, a few things by Virginia Andrews, The Moon’s A Balloon by David Niven (whoever he was) and the complete works of Miss Read.

And I never really realised what it meant to have a novelist for a granny. I don’t think I understood, first, what an achievement it was, and, second, how much it influenced me – not so much as a writer but simply in the fact of becoming a writer. There are no writers elsewhere in the family, unpublished or otherwise, except for me and my brother. We’re not a bookish clan. But somehow I got hold of the idea that a person, a normal person, can just sit down and write a book and get it published and become a writer and there you are. I got hold of it and kept hold of it, and here I am – a writer, just about.

The idea came from my granny, of course.

This week, I finally read it, Strange Heritage, my granny’s first novel – that is, the first novel by Kathleen Heaton. She was sixty when it came out. My granddad was still alive and they would have been living in Wrenthorpe. She’s ninety-two now (and my granddad’s been dead for ages). She’s always been close by, my granny – we’d go to hers on a Thursday, she’d come to ours on a Monday, and Christmases and summer holidays were always spent together – but we weren’t, in that other sense of the word, close. There’ve never been meaningful conversations or heart-to-hearts over the tea and fig-rolls. My granny’s always just been there, in the most literal sense – and that’s always been enough. For me, anyway. I think maybe she would’ve liked at least one or two meaningful conversations.

I think me reading Strange Heritage might be our last shot at it. Because it is a conversation, reading a book; you listen, you assent or you disagree, you might not say anything out loud but your head is crowded with yes, buts and no, actuallys and what abouts and that’s it exactlys.

So what sort of conversation did I have with Strange Heritage?

It’s a novel of its time, a Gothic romance set in a not-very-specific Past, and it’s all mills and moors and illegitimate children and ne’er-do-well firstborns. There’s much business with ghosts and murders and a mad maidservant (who’s pretty good actually) and it ends with comeuppance for nasty m’lady of Mill House and love with the hunky Mr Downey for the heroine, Eliza Jane Stancliffe, the sensible-but-curious orphan girl who loves Wuthering Heights and knows her scripture (reminds me of someone I know).

It’s not – as I knew it wouldn’t be – the kind of novel I really admire. The dialogue’s stiff and the plot development is workmanlike, to say the least.

I liked it, though. Well of course I did.

It was a novel and moving experience to see my granny’s thoughts and feelings set out on a page, to be presented with them in the same way I’m presented with the ideas of, say, Vladimir Nabokov or Jonathan Coe or Thomas Hardy (the authors of the three nearest books to my desk as I write).

The best bits are incidental. I liked the description of the unloved old house that is “like a corpse laid out in splendour in a handsome coffin with brass handles” and the glum room that “looked and felt like the bottom of a muddy pond”. I liked – very much in spite of myself – the spunky kitchen-girl Violet, who talks in dialect and says things like “Most of us ‘ave to be ‘ere a year before we can dust the aspidistras”.

My favourite bits, inevitably, are the bits that feel personal, unique to the author – the bits that are the best part of any conversation.

Eliza Jane, self-taught and well-read, talks about books a lot – “not just the things they told me but the words they used to do it”. The kindly bookseller Mr Bamforth tells her to “live on beauty, child. It is cheaper than cake and much, much more wholesome.” Amid the melodrama and stock characters, here is a glimpse, perhaps, of how my granny feels about books. And it’s maybe not a far cry from how I feel about books.

The very best passages are about ‘Tanfield’ and the surrounding countryside. She’s a child of the industrial West Riding, as am I, and the novel has some good, dark, Hardy-esque allusions to the region’s history (she writes about the Luddites who “broke the looms to stop the progress that was bound to come”). About the moors, she writes:

It seemed to me that the rough beauty of the countryside had a fearlessness about it, a certain staunch independence that went well with its history… The mills always fitted in well with their brave surroundings. The moor, wild and empty, the solid drystone walls and even the scrubby grassland lost none of their strength, summer or winter… It all seemed to add up to one thing. Achievement.

I don’t say that it’s great writing. But it means something – to me, anyway – that the writer looked out on the moors around Huddersfield and felt something that she was moved to write about – ‘cause I know what that feels like.

I remember my granny’s typewriter. It had fat black keys and a custard-yellow body.

I’m writing this on my granny’s laptop. My mum and her sister bought it for her a few years back, but she couldn’t get to grips with it, so it found its way to me. It’s getting on a bit now (like my granny). The letters on the keys are extra-large so that she could read them.

The title, Strange Heritage, refers partly to the events of the novel, which concern family and inheritance, but also to the idea that, in accepting what our shared history leaves us, we inherit a lot of bad along with the good – or vice versa, if you prefer.

There’s an excellent paragraph describing a town scene that my granny must have been very familiar with, growing up in pre-war Huddersfield.

The shopkeepers were used to the dirt at this time of year, on the floor as well as on the shelves and in the folds of the curtains, and young mothers agonised over the soot specklin their babies’ faces and the rows of white linen strung across the tiny backyards… Cheerful women sat precariously on upper windowsills, their legs trapped by the upper sash of the window, while they fought the useless battle with the dirt that was part of their heritage.

Strange indeed, the things that come down to us from the generations that went before. We seldom see them coming, but they are why we are what we are.

Richard Smyth is an author and award-winning short-story writer. His first novel, Salt Pie Alley, will be published in 2014.

I loved this Richard, especially since only this morning I have been sorting through my late grandmother’s possessions (she died in 1989). It’s a cliché but we often take our loved ones for granted, and it’s the little things like your grandmother’s book and my granny’s knick knacks that reconnect us to the relative we knew/know and reveal a little to us of their spirit and character. A wonderful piece.

Hi! Do you use Twitter? I’d like to follow you if that would be okay.

I’m absolutely enjoying your blog and look forward to new posts.