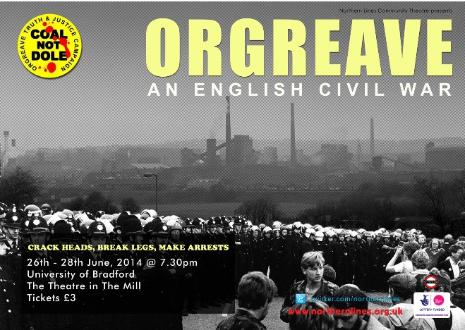

Rich Jevons talks to Javaad Alipoor on Northern Lines’ Orgreave: An English Civl War and Soroush’s new production My Brother’s Country.

RJ: Could you tell us a bit about your show Orgreave: An English Civil War? What particular take did you put on it compared to the Jeremy Deller film Battle of Orgreave and more recently Boff Whalley’s We’re Not Going Back?

We acknowledge the fact that a lot of good work has been made about the miners’ strike and so I looked at what I had to contribute. We wanted to play around with a neo-epic theatre in a way that does have some connotations with Bertolt Brecht. So we’re trying to function on two levels: one which is the big sweep of history, the notion of the historic moment or the world spirit at any given time; and another which is the level of everyday, the interactions of everyday people.

So what we were trying to do with Orgreave really was put the miners’ strike in a much bigger context, the context of a thousand years of working class struggle. We were trying to find parallels or echoes of movements like the Diggers, the Ranters and the Chartists.

What kind of reaction did you have to the show?

It was brilliant. The Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign http://otjc.org.uk/ got involved with it so there were people attending who’d been there on the day. Anne Scargill, Arthur Scargill’s ex-wife came to see it one night. And we got our first reviews including a really nice one in the Morning Star.

All the work that we do is quite community-focused, it comes out of the R&D that we share with the community and in Orgreave there was a big community cast. What was interesting was that because of the changes that have happened since the miners’ strike for the older cast members unions were the first point of call when they got a job; whereas the younger people in the cast didn’t even know what trade unions were.

With My Brother’s Country I was interested in the form because you’ve used monologues. What appeals to you about doing that?

They’re all poetic takes on real characters, it’s not a journalistic piece or verbatim or anything like that, but Forough Farrakhzad [who speaks the monologues] was the great poet of modern Iran – I half-jokingly refer to her as the Iranian Sylvia Plath. She writes quite gloomy poetry, very much with an authentic woman’s voice which got her into a bit of trouble. She tried to commit suicide and then died tragically early.

In the play she’s the character that has a grasp on the world because she’s able to talk in a non-literal way as a poet. So we were really interested in using her as a character who, although not a traditional narrator, communicates on the storyline like a chorus to the audience. She discovers the truth of the country around her through her poetry. I used monologues as well in my piece Hole and I like that idea that people can just stand up and say things to an audience.

Are you looking at Iranian poetry in a contemporary or historical sense?

Both really. The history of the poetry of the Persian language is quite an interesting one. You could say that England is a country of theatre, Russia a country of novels, and for Iran it’s poetry. 20th century Persian poetry is an attempt to break from what is sometimes perceived as a prison of the past, famous Persian poets like Omar Khayyám. A lot of the later poets have been trying to break out of the vocabulary and system of rhyme that they felt didn’t connect with the world around them any more.

How important is the relationship between Islam and sexuality to the current piece?

It’s within how Islam and sexuality and Islam is viewed in the West we can see the history of the Western relation to Islam. If we go back 150 years we had the Orientalist movement where the vision of the Islamic East is very lascivious, it’s all about harems and what at the time would be perceived to be sexual deviance. And there are books like the so-called Islamic Kama Sutra, The Perfumed Garden, which has been translated into the European languages.

Now we have this stereotype of puritanical Islam, much less liberal. Sexuality is so fundamental to a human being in terms of how we see other people. So in this show we’re trying to complicate that and provoke people. It’s about the way the West exoticises the East.

Could you tell us a bit about the main character Fereydoun Farrokhzad, and what interests you in him?

He was a very impressive guy who went to the West as a very young man to do a PhD in Germany in political science and he became a successful poet in German and did radio shows for ethnic minorities in Germany. Then in the late 60s he was invited back to Iran by the Shah’s regime and he became famous as a showman, a big icon who could make and break people’s pop careers. He really pushed things in terms of what you could get away with.

He could be sometimes very cruel and selfish, but always very brave. He was murdered in Germany in 1992 in his flat and he was stabbed horrendously. The German police think there was more than one assailant – he was stabbed 26 times in the mouth alone and 70 times all over his body. This was very much a statement to send and the German police never solved it.

So what struck me as interesting was that there are so many people you could blame: the Iranian regime, the Mujahideen, or just a man he met and invited home. So what interested me was the journey that takes you from being beloved of a whole country to a place where almost every political faction has a motive for killing you. So the play is not a whodunit, it’s a whydunnit.

How have rehearsals been going?

It’s been really cool because it’s a six-week process which is important because it gives us time to sort of ‘play’ which is good when it is conceptually quite deep about post-colonialism and Orientalism. It’s a process of discovery.

My Brother’s Country runs at Theatre in the Mill on the 20th and 21st February.

Click here to read Rich Jevons’ interview with Javaad Alipoor on Hurr, and here to read the review.