The Ghosting of Temple Works… the White Elephant in the Room meets God’s Own Raincoat.

A commentary by Susan Williamson, director of the suspended Temple.Works.Leeds cultural project…

The potted history is this. If you want the full story, read on after the pause…

How does an enormous historic building becomes ghosted?

Its suitor stops returning calls. After years of flirting, best-friending and gone-viral hooleys, Temple Works is slowly fading from sight as its latest, most glamorous lover loses interest. And that was after a promised rescue from the poorhouse and those crazed car park attendants, a vow of marriage with concomitant surgery.

Holbeck’s glorious Grade One Listed Temple Works, scene of those industrious sheep and fifty years of the Kays’ Catalogue range of Northern leisurewear, may have regressed 12 years back to an unoccupied state of collapse. Burberry’s support for a project which was to have seen builders on site this year is now “on pause”, and has been for almost 11 months. And yet the Council swears nothing has changed since the original far-reaching agreement with them of November 2015.

We have no reason not to believe the Council: it is all in the public domain.

Why the “pause”?

Well, ask yourself: why in the end does Burberry need or want Temple Works, except as a contractual means to an end to gain land for a modern central Leeds relocation for an existing, fully functional nearby two-site manufacturing plant? They don’t need to prove their much-repeated commitment to Yorkshire heritage: they have been proudly, presently Yorkshire for 100 years. But as the economic climate veers off course once again due to Brexit, they might be mad to change their status quo for the sake of brand image.

In the meantime,Temple Works has been left unceremoniously vacated, precariously unoccupied, and largely uncared for after the departure of the Temple.Works.Leeds cultural project. Hands-on knowledge, cultural experience and commitment, revenue and audience have fled to the four winds.

Back to the bad old car-park days for Temple Works then.

Or is it? Is there still a way out?

PAUSE FOR DRAMATIC EFFECT…

All relationships have timelines, and Temple Works has four of them.

The first is that of the building itself.

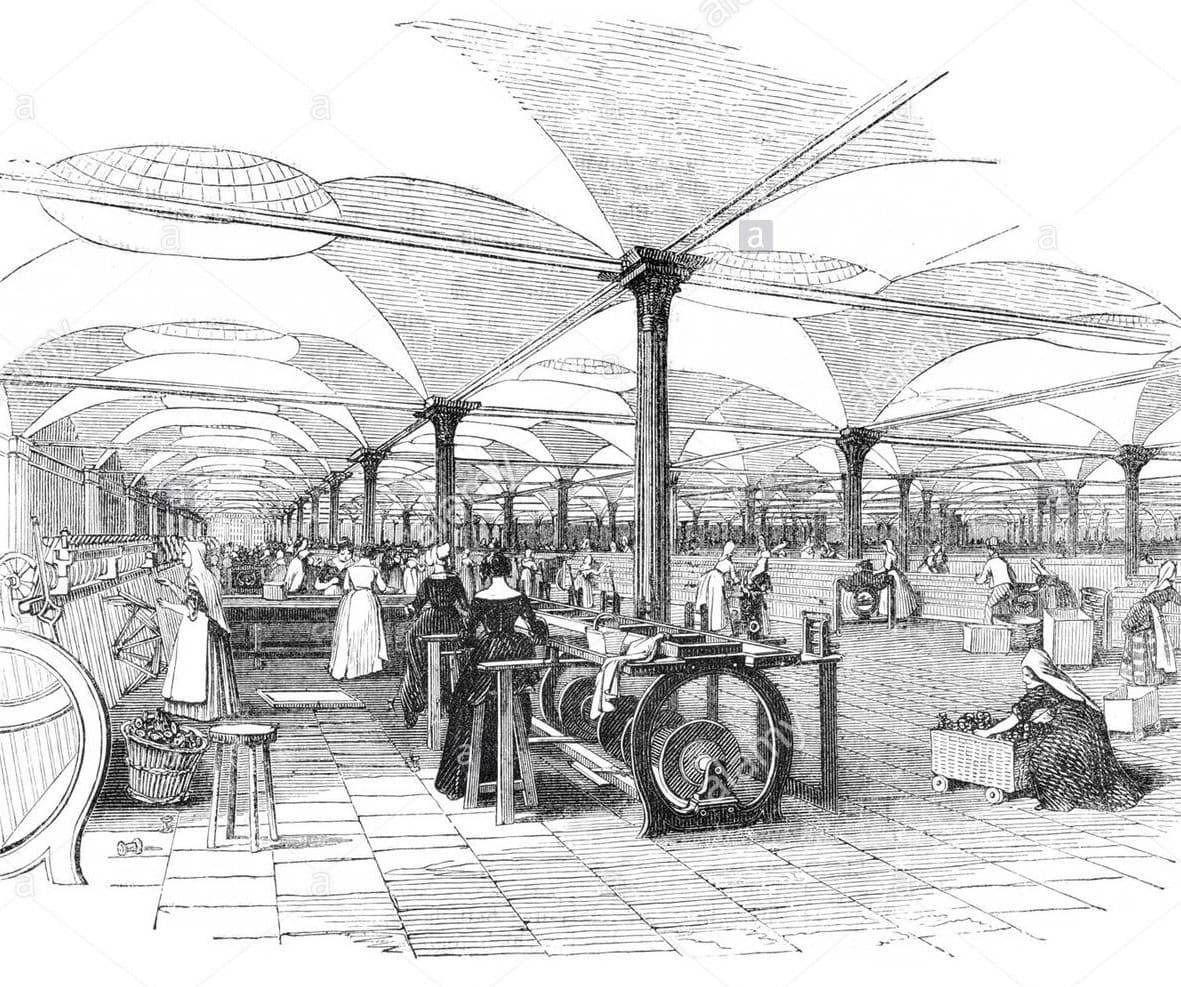

This most outrageous piece of engineering was built in the spirit of Victorian industrial invention in 1838-1840, failing immediately during construction and receiving an even more outrageous bodge-job solution to keep it standing – more or less – until today. From the Bonomi Brothers to today’s legion of bemused engineers, no one can say with absolute certainty why or how TW is still standing. In fact, it barely is.

The second timeline is that of Temple Works’ rich industrial and social history.

Begun as a flax mill with kibbutz-like practices involving working women, basement dorms, educated children and frozen worker-sheep, it moved past the transformation of the flax market into that of cotton via several iterations as a textile mill, to its longest lasting narrative in 1953 as Kays, ‘Britain’s Favourite Catalogue’. At the time of its closing in 2005, it was South Leeds’ biggest single employer. Families were built on this.

The third timeline is known as Temple.Works.Leeds, the successful, alternative, self-funding cultural project begun in 2008 with its current owners’ support, suspended by Burberry’s force majeure in 2016.

This project’s original intention had been to create a Tate-level national and international cultural venue with a strong commercial basis, with active support for and involvement by local and regional cultural groups. Escalating repair costs of the deteriorating main spaces – coinciding with risk-averse potential investors during the recession – saw this turned on it head from 2010, with local and regional individuals and groups taking the lead instead.

But the fourth timeline trumps the first three: a series of random stop-starts and slow deaths, punctuated by spikes of enthusiasm and dire predictions by johnny-come-latelies and heritage bodies, a series of 3 planning applications, no City Council interest for years after the death of Yorkshire Forward, resulting investment and hugely commercial cultural opportunities come and gone, the shoving under the carpet of the ill-conceived Holbeck Urban Village, the rapid growth of and now current Brexit-blamed uncertainty surrounding the South Bank development.

So what happened?

In 2013, Temple Works’ current owners asked me, as director of Temple.Works.Leeds since 2008 and original regeneration consultant with colleagues, to find a way to move the very stalled project on. They were not – and have never been – developers of cultural venues. They had been trying to find a graceful way to honour Temple Works’ heritage and that of Kay’s (which they owned) while divesting themselves of a massive but potentially very valuable white elephant, but whose value they themselves could not realise other than as adjacent land and more modern buildings. This was the white elephant in the room of the Temple.Works.Leeds project for years. No one wanted the elephant that had not already ridden on it. And no one was ready to take on the commitment to gain the huge funding needed for repair unless they were already passionate about its cultural potential or – convinced and ready for this – accompanying diverse and supporting development.

With help from other cultural communities around the UK, we at Temple.Works.Leeds made a proposal to the supportive current owners and then to Leeds City Council for a community buy-out of the historic site. The council would enable taking the building back into public ownership with the owner’s’ acquiescence. This would have been followed by our taking control through our Community Interest Company, and then applying for heritage funding for required repairs and restoration. We had national and international commercial cultural partners ready and willing to invest in revenue-making programmes to keep it – as it has always otherwise been – self funding.

At the same time the development opportunities in Holbeck were apparent even during the late recession, so we were delighted when a local, green and very successful developer approached us. They wanted to meet the current owners and look at how to make the project self sustaining with us (as artists and commercial cultural events-holders) on a broader basis through housing, leisure and retail. They designed and tested comprehensively a green, sustainable, diverse project that while it did not immediately achieve public funding, had English Heritage and Leeds City Council support. The anticipated shortfall they were confident of making up through private funding, right through til Autumn 2015.

And then there was a bolt of lightning as the recession receded, developers and the Council got a late-Spring fever, all hell broke loose, and over the horizon, came Burberry…

Burberry and Yorkshire

Although an international luxury brand spanning outerwear, high fashion, accessories and cosmetics, Burberry is well known to have a long-term presence in and commitment to Yorkshire. The famous tan raincoat is of Yorkshire-woven gabardine with a local industrial history of 100 years, in long-term production at 5,000 raincoats a week. 800 raincoat manufacturing jobs have long existed in Castleford and Keighley, all of which were set as part of Burberry’s proposal – to the consternation of local employees – to move to Leeds, with the promise of a further 200 jobs “in the future”. The Burberry Creative Director (who was until recently also the CEO) is a young Yorkshireman, the inspired eye behind Burberry’s more recent and successful cutting-edge brand appeal.

Local developer out, Community Interest Company out, big brand in…?

It is not for me to comment on how and why the green developer’s fully funded, supported, culturally coherent proposal was excused in favour of Burberry’s surprise offer in October 2015. I have been told by the Council that they were as surprised as I was by Burberry turning out to be the latest “mystery” suitor – and to be fair, the decision was not theirs to make. The offer – which then sped through the Council’s Executive Board with almost unseemly haste in November 2015 – was to to take on a larger chunk of Holbeck with the Council’s help and that of the current owners, on the commitment that they would as a quid pro quo also take on and restore to public, cultural use the very vulnerable historic buildings at Temple Works.

In anticipation of a an imminent purchase, the Temple.Works.Leeds cultural project was suspended February 2016 as we were unceremoniously moved out after almost 9 years to offer vacant possession. The promise however by the Council was that of Burberry engaging with our suspended cultural project going forward when plans for the historic buildings became firmer, and the Council made it clear, and continue to do so, that they expect this to happen. Indeed we communicated with Burberry about this at the time and afterwards. We have not heard back now despite polite reminders for some 16 months.

188,000 visitors to an unheated, unlit, mostly unpowered crumbling monument, with the infamous one public toilet – and users ranging from Jamie Reid, punk and Makossa festivals, to BBC, ITV, Channel 4 and independent filmmakers, heritage and educational conferences – all unfunded, revenue-based and supported by cooperativism and voluntarism – kept the place growing culturally and cared for painstakingly by hand. All people and props left in 6 winter weeks, along with Elvis, and the site once more became a rather nasty pigeon-run carpark awaiting the arrival of The Famous Tan Raincoat.

So: Burberry’s own timeline, now “on pause”

From significant Press coverage and a helluva lot of excitement in late 2015, “public consultation” on South Bank proposals through to March 2016, the unveiling of the multi-investor South Bank plan in Spring 2016, the appointment of Burberry’s Stirling Prize winner architects Stanton Williams in April 2016, the poorly-detailed hyperbole flowed. A start date on the Burberry manufacturing plant and on the restoration of Temple Works was promised for this year. Developers CEG decided to co-opt the Temple Works name for their overall South Bank development, giving it the cheap ‘n easy “Temple Quarter” brand, while omitting to refer to any plans for the historic buildings over which they in any case have no control.

Then the June 2016 Brexit referendum saw a rapid backtracking by Burberry on its commitment to South Bank for its new manufacturing plant and to Temple Works itself. But in spite of the fact that their raincoat is the cash-cow of the business, never faltering and virtually Brexit-proof, and in spite of enviable worldwide profits, an invincible brand and its much vaunted commitment both to Yorkshire and the the project, Burberry has said repeatedly for the last 10 months that it is “putting the project on pause”.

Where does ownership currently stand?

The City Council – with whom I have checked regularly – have said repeatedly that as far as they are concerned the agreement and commitment date to look at is still November 2015, and that “nothing has changed since then”. And yet while it is on record that Burberry has purchased the Temple Works-propping 1953 Reality Building from the current Temple Works owners, and the adjacent old Kays’ building land on Sweet Street, as well as land on Bath Road with the help of the Council, (and have been promised £750,000 towards the creation of an urban park to the front of Temple Works), it is noteworthy that they have NOT yet purchased the three interconnected buildings that comprise Temple Works from the current owners. Their recent purchases can of course change hands any time, if they no longer need them.

The Ghosting of Temple Works… and a Leeds consolation prize?

Indeed, Burberry has stopped referring to Temple Works publicly at all since the 2016 referendum. Last month they once again announced that they were “thinking through” their stalled Holbeck manufacturing plant, once again also failing to mention Temple Works itself, or the fact that they had not gone through with their promised purchase of the historic buildings themselves – without which they will not supposedly have a deal overall with the Council for the manufacturing plant.

Their latest Leeds news this month was instead that they would be opening a “shared service centre” in Central Leeds with 300 personnel, moving a number of service departments in together from other places in the country. Once again they reiterated their commitment to Yorkshire, while now failing to mention the manufacturing plant – stalled or not – at all, or indeed Temple Works itself.

Is this a soft way out of the manufacturing plant and historic Temple Works, by offering a consolation prize for Leeds?

Some scares for Burberry… when the status quo may be the more attractive option.

I am no cynic, but I can read between the lines, and as a long-ago economist before architecture got me in its grip I can also read a company’s Press and published results. I have spent now some decades as a consultant on very big private and public commercial and regeneration projects, and what I have come to know is that situations with clients such as these are often a lot more simple than they seem through the obfuscatory haze of outside speculation. If it looks commercially odd, and unsustainable, it probably is unless there is huge backing. Or else it might just be a mess.

It would be hard to doubt Burberry’s commitment to Yorkshire as a critical part of its brand, nor its presence continuously in the county for 100 years. It is undoubtedly a well-admired world-class act, and while you will catch few Yorkshire folk actually sporting its £1,000 raincoat of an evening, most in the region are proud of its links to Yorkshire’s textile heritage.

It is indeed God’s Own Raincoat.

But after a scare in 2008-2009, several false starts in its recovery through brand diversification, volatility in the international luxury market brand market, and changing appointments at the top, it is not completely surprising to many, myself included, that Burberry is playing it as safe as possible. With the Brexit excuse, they may better “show support for Yorkshire” by staying put in the two current plants, and quietly exiting the South Bank project while placing a much smaller department in Leeds city centre to show willing. The raincoat after all is the stable business needed to keep the rest of the ship afloat… so why rock the boat and spend millions on its Yorkshire plant relocation if they don’t need to? Because that white elephant is still in the room… they will have to spend millions on Temple Works for no observable commercial benefit to themselves, in order to relocate their manufacturing plant from what appear to be perfectly acceptable current locations.

Time to revisit other options?

Is it time to revisit one or the other of the two best researched, local proposals of 2013-2015: a local green, privately funded developer, with the community/ commercial cultural partnering? Or the sale via the Council of the historic site only, to a Community Interest Company able to gain heritage funding and commercially successful cultural partners? All of us are exhausted after years of hard work and uncertainty, so this may be a quixotic question at best… but then…

The Council states repeatedly that Temple Works is one of its two priority heritage projects, the other being Hunslet Mill. While I have no cause to disbelieve their current considerable support, especially that of the CEO and the Regeneration team, there were five crumbling years when the Conservation team did not visit Temple Works at all. (I know: I was the gatekeeper in charge of the signing-in book!) Then in September 2014, after a flurry of interest at regional level by English Heritage, I was asked to present the project as a headliner at a national Prince’s Regeneration Trust conference. I refused to present it as requested as a ‘meanwhile use’, but as a living, growing-use, revenue-reliant project needing investment for repair. I asked for help publicly at that conference, and was assigned an inspired social-investment banking expert who worked at linking these two together: private development with a social commitment, and community-led cultural “ownership” teamed with a national and international events programme. So: we DO know this is possible.

And there is always a third option…

We always said Temple Work had real value too as a ‘beautiful ruin’ in the manner of the Acropolis – a proper urban garden with the remnants of its magnificent structure there to suggest new, partially outdoor cultural uses. We worked with engineers on this possibility. But we never wanted to wait for it to collapse ignominiously in order to achieve this.

…for those who care

We also know that only those who actually care for the site, its history, heritage and more recent usage and have unfeasible amounts of staying power, care enough to go through with this project long-term.

If you have never been to a Temple Works event of up to 1,000 music-driven people and seen the sun rise at the end, spent a dark night filming and sound-recording in the extraordinary acoustics of the Main Space and heard it “sing”, painted in sub-zero temperatures, pored over hundreds of stories offered by people of their years working at Kays, listened to the buildings’ demands while probing every nook and cranny over its many acres to see what needs were to be attended to to keep it alive, you can have no possible understanding of its real value and its real future potential. And there IS real cultural and commercial value: but it is only known to those who have already done it. (See templeworksleeds.uk for a legacy of users and celebrations to date.)

So why would Burberry value historic Temple Works enough to commit – for years hence – to a white elephant they must rebuild for millions, for a purpose they do not need commercially or culturally other than as a 2-acre Museum for God’s Own Raincoat, before being allowed to build their real objective, a modern, Yorkshire manufacturing plant they may not currently need?

photo credits to Jim Moran, Joolz Diamond, Si Cliff, Susan Williamson, YEP, CEG and Burberry.

Temple Works, like many other areas of Leeds City Centre South still haunted by post industrial dereliction, is emblematic of a city without a plan.

Leeds has no shared, pragmatic framework for delivering sustainable regeneration in an area that has been crying out for an innovative masterplan for well over a decade now.

‘Leeds City Centre South’ was identified as offering a ‘once in a lifetime’ opportunity for the city of Leeds to do something special in the realm of urban regeneration and sustainable development seven years ago. The opportunity to re-connect communities to the south of the area to the affluent city centre is at the heart of this.

‘South Bank’, as now badged by LCC, is being actively promoted as the largest city centre development in the country. It remains without a published masterplan or framework. Sites are being ‘picked-off’ by developers and planning approvals being granted without an overall published, shared vision for the area. The most valuable developments are being brought forward and developed first.

“The Best City to Live by 2030”. The Leeds ‘Vision’ (published by LCC in 2011) is aspirational. How we all may work to achieve this vision remains to be resolved.

The current diversion of a substantially ‘creative arts’ based submission for ECoC2023 is a missed opportunity. The element of ‘culture’ in the bid is hard to discern. Perhaps the way that Aarhus won with their bid for ECoC2017 should be examined more closely. They put regeneration of the city at the centre of their thinking, badged it (in all humility) ‘Rethink’ and created the most senior post in their Council as the ‘Alderman for Regeneration and Citizen Involvement’.

Active co-creation, inclusive visioning and community partnership are all needed now in planning for the regeneration of the ‘South Bank’ if we are to achieve the declared vision.

Temple Works was on the verge of delivering something tangible and inclusive when the visionary development project was summarily ambushed in the name of political expediency.

It is a shame.

There is hope in the various ‘bottom-up’, community based initiatives working to deliver a more sustainable community in the city and the ‘South Bank’ in particular.

http://www.leeds-sdg.com

Ho Ho – There’s another Temple which requires attention.

Not quite as prestigious in appearance except for the roof lights which reflect the Holbeck original perhaps but nonetheless a very significant cultural centre.

I guess the satellite dishes on the outside might be a give-away.

This is the Virgin Media engineering and IT centre at Site 15 on the Ring Road in Seacroft and I must say I think it needs a bit of sprucing up. Actually I would suggest Ramshead Approach is a better address.

Ironically perhaps it is called Temple House.

An important cultural heritage site of the late 20th and early 21st Centuries – I should blooming well say so. Those dishes were originally put in place by Jones cable Media perhaps the first cable provider in Leeds. Of course, they didn’t last too long before they were taken over by NTL who themselves merged and became Virgin Media.

So, if you are one of the 10,000’s presumably of Virgin Media customers in Leeds and who watch your TV with them if things go wrong then here is where the guys in the white vans come from to make your repairs. Arts events in exotic venues don’t me bother too much as with the help of this hub I can stay at home and watch the screen.

I don’t know much about the early history of the building except that clearly it is part of the Seacroft Light Industrial Park which I can confidently predict was built or commissioned by the Council around the time of the major build in Seacroft in the 1960’s.

There is some ghost signage on Temple House which refers to “Family Baskets” I’m not too sure what these ambiguous words refer to.

I did discover that when it was sold to Stirling Investment Properties in 2010 they intended to redevelop the upper floors which were formerly used as a call centre, into high-quality mixed office space. There is not much sign that this has happened at least from the outside.

At that time, Virgin Media signed a leaseback on 46,012 sq ft of space on a 25-year term.

Just warming up here but what is so special about the South Bank and all those relics of Victorian venture capital. I may be going over the top here but I don’t think any amount of “nicing” these places up, giving them a new identity and converting their spaces for the industries of the future will ever remove the memory of the exploitation of the workers which took place there.

I hope I’m not coming across to pious here but I prefer what the Seacroft Light Industrial Estate represents – a moment in Leeds’s history when the local state was “empowered” to look after its citizens interest through economic planning and social housing. Fortunately, to aid memory of this period not only are some of the unchanged buildings very much in period but the City Council still has an imprint in the area with its print centre, highways and works depots and recycling centre.

Of course, there is no heritage groups interested in these places as there are in Manchester, Sheffield or Birmingham so at the moment I can enjoy at my leisure – Stoned Again – “we buy flags”, Dino Truck Catering, the shiny new JB Sports gym, Seacroft Interiors – “where quality matters” and the ultra modernist KFC.

This article was brought to you by North Leeds Liminalists – “Speaking up for the suburbs”