Should the big guy on the bronze horse in the middle of City Square be knocked off his pedestal? CHRIS GRAHAM argues it’s time The Black Prince was put out to pasture.

I am sure I am not the first person to have tried – and failed – to establish a link between the Black Prince Edward of Woodstock and the city of Leeds. Yet every time I emerge from the railway station on to City Square, there, disturbingly, is Thomas Brock’s monumental praise song in bronze to the Prince. Why?

This equestrian statue is not a thing of beauty; it is a piece of lumpish bombast, the figure of the armoured prince leaning back with arrogant hauteur and pointing (it’s rude to point) in such a way as to make it appear to visitors that they are the hated French enemy and are being invited quite unceremoniously to begone to Hunslet or Castleford or, preferably, the North Sea. Even Alfred Drury’s gorgeous nymphs can do little or nothing to lighten the drab, inhospitable heaviness weighing down upon the square from the imposing bully in the saddle.

I wish to begin an as-yet-half-baked campaign for its removal.

Removal, not demolition. I’m no iconoclast.

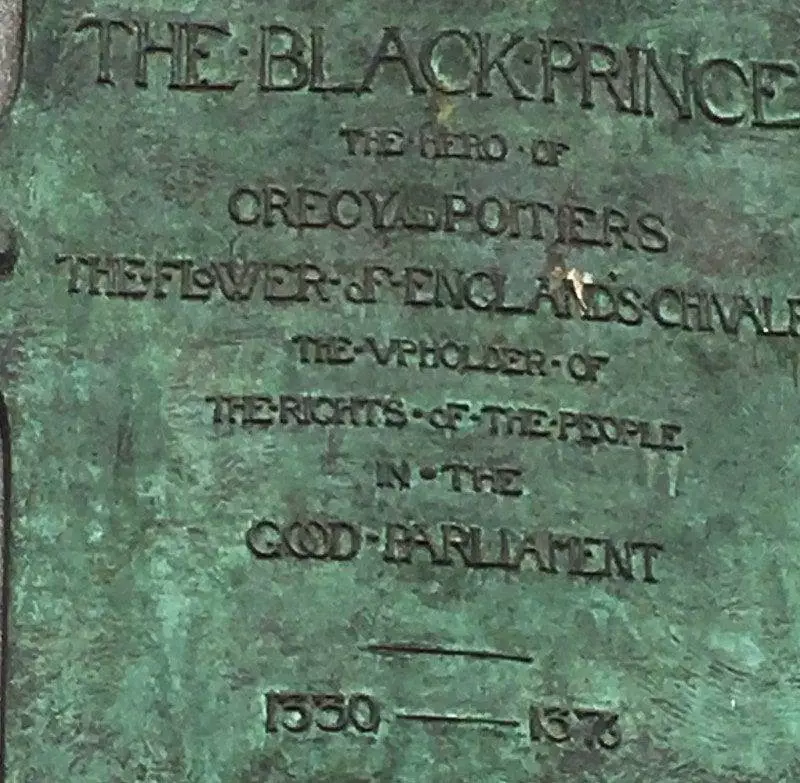

If the Black Prince (1330-1376) had enjoyed a reputation for kindness and magnanimity, or even for pleasure – a love, say, of the melodic outpourings of lutes and psalteries, or a taste for a Provençal troubadour’s lyrics – and had appeared without horse and sans cuirass and barbute, one might possibly have warmed to him. But the truth is he was a brutal, granite-hearted beast.

His theatre of cruelty was the Hundred Years War. He was notably duplicitous, cynically ignoring the medieval code of military honour in stark contradiction to the declaration on the plinth – surely an instance of highly burnished sarcasm – that the Black Prince was “the flower of England’s chivalry”.

On one occasion he butchered a thirteen-year old boy – the son of the commander of the fortress in the Breton port of Brest he was besieging. The child had been handed over to the Black Prince as a hostage against a temporary truce which had been agreed to allow both depleted sides to replenish arms and food. At the end of the truce, instead of returning the captive child as per the agreement, the splenetic Prince, furious that the fort had been restocked, his concurrence notwithstanding, had the boy killed.

An odd hero for a monument in Leeds.

Regarding the removal of the statue, I’m not suggesting it should be melted down or destroyed altogether but simply relocated – perhaps a retirement spent negotiating the gates which decorate the ring-road roundabout by the Crossgates Arndale Centre might be suitable?

There is a precedent for the re-siting of equestrian statuary. In Venice there is such a monument dating from the Renaissance, a marble paean to one Bartolommeo Colleoni commissioned from the Florentine sculptor Andrea del Verrochio. Colleoni was a typical 15th century Italian creature, a condottiere – a mercenary soldier who served the Venetian Republic, and certainly not one overcome with modesty. In his will (he died in 1475) he requested an equestrian monument be erected in his honour in front of the basilica in St Mark’s Square. The citizens were horrified, and the municipal government ordered the statue’s removal to an obscure campo on the city’s rim where it stands today.

Assuming the removal of the Black Prince, one or two supplementary questions arise – how to fill the space vacated, and what to do with Kenneth Armitage’s legs which, I suspect, were half-intended as a sort of tangential pun on Brock’s pompous prince.

Let the Armitage piece stand on its own five feet, but as for the vacated spot, perhaps the equestrian could be replaced by the pedestrian, some modern hero – Lee Bowyer perhaps, arm and hand outstretched like the Prince, making a dismissive single-fingered gesture in the direction of Manchester? Or by a velocipedian statue, a contemporary work created entirely from objets-trouvés recovered from the Leeds-Liverpool Canal, depicting a lycra-attired and goggled giant, athwart bicycle (no bell), glaring down on pedestrians who dare to step into the cycle lane at his feet? Or, maybe like the 4th plinth in Trafalgar Square?

But, no, that’s enough… The plinth has to go too.

Of course, the space could just be left empty. (There is by the way a little plaque on the pedestal with a q-code which will enable you to hear the Black Prince talking – presumably in his fluent medieval Norman. Alas my ancient Samsung lacks the necessary app so I can’t report back on this).

Nice one Chris – finely written with just that right blend of humour and provocation.

I recognise at once, however, its source of inspiration and underlying serious intent since close to the surface are clear references to Afua Hirsch’s critique of Nelson’s Column, the recent Rhodes Must Fall campaign at Oriel College Oxford and the on-going issues in the cities whose growth was based on slaving such as Liverpool and Bristol such as the debate around the renaming of Colston Hall in Bristol.

Of course, hereabouts we have our own examples notably the plantation roots of the wealth which built Harewood House and its acknowledgement or otherwise within this visitor attraction.

But moving on from colonialism and slavery, we are doing statues in the city centre, so I would just like “concretise” (not literally as it is made from something else) your piece with reference to an actual controversy which arose recently and as far as I know is currently unresolved around the re-siting of the Arthur Aaron statue from Eastgate Roundabout either to Oakwood or the Victoria Gardens outside the Art gallery.

I know I have been here before chatting about Temple Works but your piece basically supports the view which is at the heart of all these controversies that you can’t separate the object from the several memories and historical facts which surround it. “Heritage” and historically referencing statues effectively claim one meaning over several other possible meanings some of which refer to truths we are encouraged to forget.

So, lets look at Arthur Aaron and his current memorialisation. The Talking statues project you refer to states “Born in Leeds and educated at Roundhay School, World War II pilot Arthur Aaron was awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry, after dying in combat at the age of 21.”

This brief account using the words “dying in combat” to some extent minuses his heroism in bringing his plane back to base home whilst severely wounded and saving the lives of other members of his crew.

What this brief citation also does not say is that he was the pilot of a bomber engaged in an attack on Turin which opens the more complex question of what we remember though statues like these in which context is largely ignored.

If were to examine this individual act of heroism in the context of the project in which he and his comrades in Bomber Command were engaged in at the time which was the saturation bombing of German towns and cities a much more complex ethical picture would emerge. Arguments remain about the effectiveness of this campaign but what is clear that in the process it killed hundreds of thousands of German civilians, massively destroyed non-military infrastructure of housing, schools and hospitals and obliterated a large amount of irreplaceable European cultural heritage.

Interestingly, the statue itself may reflect some of these tensions of memory. The children climbing a broken tree (like a statue in former East Berlin by Gerhard Thieme) next to the body of the Arthur Aaron flyer are normally said to represent their ascent from the darkness of Nazism to the light of peace and liberal democracy (or in Thieme’s case Socialism) with the release of a dove by the child at the top. This has been brought about by the heroism of his actions and his comrades. But others might see an irony in that many thousands of children did not make that ascent suffocating to death in cellars or being burned to death in the streets.

Like yourself I am not advocating the complete removal of the Arthur Aaron statue, but I’m interested as an observer of these things both where it ends up (if it is moved at all) and what any commemorative writing on the statue will say.

I think you’re being a bit harsh about the Prince. He might have been a tough guy (they were tough guy times to be fair), but he was also the greatest king England never had, the flower of the world’s knighthood, driven by faith and duty, generous to a fault e’en though riven by debt and dysentery.

When he arrived at La Rochelle with his beautiful wife (who he married for love!! in the 14th century!!) the people of the town welcomed him “with every demonstration of joy and all those signs of popular approbation which are lighter than vanity itself.”

They clearly didn’t think he was a brutal, granite-hearted beast, did they?

And even if he were, and even if the statue is “lumpish bombast” (it ain’t), it’s our 100-year-old lumpish bombast. It was a present to the city from a local entrepreneur who didn’t like the original idea of having a public toilet in the space. The unveiling was greeted by loud cheers from the assembled throng, much like the good people of La Rochelle welcomed the Prince himself in times of your.

So leave it alone.

And be afraid too of what you’d get in its stead. Not a chance of Canning Town boy Lee Bowyer nor even of Leeds (born and bred) most famous ’60s pop stars Paul & Barry Ryan, now disgracefully edited out from Leeds storytelling. Replacement equine statuary is almost certainly in the gift of the Leeds BID. You might get a post-modern representation of “Compassion is in our DNA” in squiggly day-glo. Do you really want to take that risk?

I share your concern for what might replace it (that’s the self-admittedly ‘half-baked’ ingredient of my plan). Mr Bowyer was a flippant part of the vision to be dismissed as quickly as contemplated. I favour an ensemble of Leodensians but as you imply this would not be in our gift. Re Prince Edward’s charms and, indeed, chivalry, I think we will have to accept we gathered our history from different sources though have no desire to shut my mind to alternatives (especially now my heart has been softened by the dysentery and the beautiful wife). In the end my argument for the statue’s relegation to a distant suburb arises mainly from aesthetics rather than history.

Nice one Chris – finely written with just that right blend of humour and provocation.

I recognise at once, however, its source of inspiration and underlying serious intent since close to the surface are clear references to Afua Hirsch’s critique of Nelson’s Column, the recent Rhodes Must Fall campaign at Oriel College Oxford and the on-going issues in the cities whose growth was based on slaving such as Liverpool and Bristol such as the debate around the renaming of Colston Hall in Bristol.

Of course, hereabouts we have our own examples notably the plantation roots of the wealth which built Harewood House and its acknowledgement or otherwise within this visitor attraction.

But moving on from colonialism and slavery, we are doing statues in the city centre, so I would just like “concretise” (not literally as it is made from something else) your piece with reference to an actual controversy which arose recently and as far as I know is currently unresolved around the re-siting of the Arthur Aaron statue from Eastgate Roundabout either to Oakwood or the Victoria Gardens outside the Art gallery.

I know I have been here before chatting about Temple Works but your piece basically supports the view which is at the heart of all these controversies that you can’t separate the object from the several memories and historical facts which surround it. “Heritage” and historically referencing statues effectively claim one meaning over several other possible meanings some of which refer to truths we are encouraged to forget.

So, lets look at Arthur Aaron and his current memorialisation. The Talking statues project you refer to states “Born in Leeds and educated at Roundhay School, World War II pilot Arthur Aaron was awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry, after dying in combat at the age of 21.”

This brief account using the words “dying in combat” to some extent minuses his heroism in bringing his plane back to base home whilst severely wounded and saving the lives of other members of his crew.

What this brief citation also does not say is that he was the pilot of a bomber engaged in an attack on Turin which opens the more complex question of what we remember though statues like these in which context is largely ignored.

If were to examine this individual act of heroism in the context of the project in which he and his comrades in Bomber Command were engaged in at the time which was the saturation bombing of German towns and cities a much more complex ethical picture would emerge. Arguments remain about the effectiveness of this campaign but what is clear that in the process it killed hundreds of thousands of German civilians, massively destroyed non-military infrastructure of housing, schools and hospitals and obliterated a large amount of irreplaceable European cultural heritage.

Interestingly, the statue itself may reflect some of these tensions of memory. The children climbing a broken tree (like a statue in former East Berlin by Gerhard Thieme) next to the body of the Arthur Aaron flyer are normally said to represent their ascent from the darkness of Nazism to the light of peace and liberal democracy (or in Thieme’s case Socialism) with the release of a dove by the child at the top. This has been brought about by the heroism of his actions and his comrades. But others might see an irony in that many thousands of children did not make that ascent suffocating to death in cellars or being burned to death in the streets.

Like yourself I am not advocating the complete removal of the Arthur Aaron statue, but I’m interested as an observer of these things both where it ends up (if it is moved at all) and what any commemorative writing on the statue will say.

Thanks for your considered response, John. I’m sorry I haven’t replied sooner but I was baby-sitting yesterday evening and overnight and thus busily engaged and I was keen to wait until I could give your post full attention before commenting. Thanks for tracing my sources of inspiration. I must admit they were not at the forefront of my mind as I was writing the piece but can acknowledge they were almost certainly lurking in subterranean wells.

I think my initial reaction to the statue (in let’s say c1990) was visceral or sensual – along the lines of “good grief, what an eyesore!”. It could, frankly, have been a monument to anyone – I was repelled by its bulky ugliness. Commuting in to work for many years by train, daily confrontation did little to soften this initial impression. But the piece nevertheless made an enduring, even if unsympathetic, impression and I had to know more.

As a native of Halifax domiciled in Bradford, it may seem a piece of effrontery for me to get on my high horse (so to speak) and pass comment on municipal decisions made by Leodensians. I’m not sure how much of a suffrage I’ve earned to allow me to offer my two penn’orth by having worked in the city. Leeds Citizen below makes a compelling case for the Black Prince by suggesting that although Prince Edward himself may have had nothing to do with Leeds, his monument – after 120 years of residence – has earned squatter’s rights.

Which brings us to the real core of the discussion – what one might call, for the sake of shorthand, the historico-ideological argument. As a (now retired) librarian, I always considered rigorous opposition to censorship as one of my profession’s defining cornerstones. I was aware, even as I was writing my piece, that junking the Prince (and similar attempts to obliterate, obscure, euphemise, sanitise the material past) was almost a physical equivalent of ‘no-platforming’ or censoring. In order to deal maturely with the ethically ambiguous, perhaps we need to be less in thrall to the curated narrative. As a perhaps trivial aside I was over in Manchester earlier in the week and visited the City Art Gallery there and was interested to note that in two or three places the gallery had invited and showcased non-curatorial commentaries on the works. The fact that some of the comments were jejune in the extreme (Victorians are always easy to kick) didn’t detract from what seemed like an interesting departure as one was reading opinions challenging uncritical immersion in received canons and orthodoxies. Your contribution to the Arthur Aaron statue would make for fascinating reading were it admitted.

I am ashamed to say I knew little of nothing about Aaron or his statue until you mentioned him and it. I fear that my rare encounters with the Eastgate roundabout have always been when rushing either to the Playhouse or the bus station rather than lingering in a spirit of diligent and reflective exploration. I shall make just such a visit the subject of my next excursion.

I realise I haven’t engaged fully with all your points, but thanks for your detailed reaction.

Did my reply to this post disappear into the ether or is it awaiting moderation? Unfortunately (for me) I didn’t save a copy so if it has vanished, would have to recompose.

Ah, now I see why yesterday’s reply didn’t register; it was ‘detected as spam’ by the Disqus engine I used in an attempt to post it. So here it is, re-posted for what it’s worth. I was more anxious to acknowledge your thoughtful reply than to offer anything substantial in the way of furthering the debate. I haven’t bothered to edit this apart from correcting a typo and a couple of verbal infelicities I spotted:

Chris Graham John Sour a day ago

Detected as spam This isn’t spam »

Thanks for your considered response, John. I’m sorry I haven’t replied sooner but I was baby-sitting yesterday evening and overnight and thus busily engaged and I was keen to wait until I could give your post full attention before commenting. Thanks for tracing my sources of inspiration. I must admit they were not at the forefront of my mind as I was writing the piece but can acknowledge they were almost certainly lurking in subterranean wells.

I think my initial reaction to the statue (in let’s say c1990) was entirely visceral – along the lines of “good grief, what an eyesore!”. It could, frankly, have been a monument to anyone – I was repelled by its bulky ugliness alone. Commuting in to work for many years by train, daily confrontation did little to soften this initial impression. But the piece nevertheless made an enduring, even if unsympathetic, impression and I had to know more.

As a native of Halifax domiciled in Bradford, it may seem a piece of effrontery for me to get on my high horse (so to speak) and pass comment on municipal decisions made by Leodensians. I’m not sure how much of a suffrage I’ve earned to allow me to offer my two penn’orth by having worked in the city for many years. Leeds Citizen below makes a compelling case for the Black Prince by suggesting that although Prince Edward himself may have had nothing to do with Leeds, his monument – after 120 years of residence – has earned squatter’s rights.

Which brings us to the real core of your response – what one might call, for the sake of shorthand, the historico-ethico-ideological argument. As a (now retired) librarian, I always considered rigorous opposition to censorship as one of my profession’s defining cornerstones. I was aware, even as I was writing this piece, that junking the Prince (and similar attempts to obliterate, obscure, euphemise, sanitise the material past) was almost a physical equivalent of ‘no-platforming’ or censoring. In order to deal maturely with the ethically ambiguous (and here I’m heading towards your analysis of Aaron), perhaps we need to be less in thrall to the curated narrative. As a perhaps trivial aside I was over in Manchester earlier in the week and visited the City Art Gallery there and was interested to note that in two or three places the gallery had invited and showcased non-curatorial commentaries on the works. The fact that some of the comments were jejune in the extreme (Victorians are always easy to kick) didn’t detract from what seemed like an interesting departure as one was encountering opinions that called into question and challenged directed readings of canonical works and recycled historical orthodoxies. Your contribution to the Arthur Aaron statue would make for fascinating and challenging reading were it admitted.

I am ashamed to say I knew little of nothing about Aaron or his statue until you mentioned him and it. My rare encounters with the Eastgate roundabout have always been while rushing either to the Playhouse or the bus station rather than lingering thereon in a spirit of diligent and reflective exploration. I shall make just such a visit the subject of my next excursion.

I realise I haven’t engaged fully with all your points, but thanks for your detailed reaction.

Hello Everyone Marjory Primm here.

I’d just like to mention one statue that I really think ought to go. That’s the fat man with a barrel outside the St John’s Centre. I mean it’s just so wrong in so many ways. It really makes me squirm when I come out of the Age Concern café having done my weekly volunteering slot behind the counter.

The issue is its brazen celebration of alcohol which should not be tolerated. Of course, I took the pledge as a little girl at our local chapel the dreaded drink has never passed my lips, but I have no hesitation about speaking out about its harmful effects both on individuals and society at large.

Need I say more but I will anyway. Don’t people realise with have a health crisis in the city made worse by people’s over indulgence. All the health ill effects are well known in terms of liver disease etc but what is completely ridiculous is the that some of these are reflected in the statue itself. The poor man carrying the barrel is completely over weight and obese. Surely, he is heading for cardio vascular disease, type two diabetes or cancer. But people won’t be warned.

Of course, the government and the City Council have not helped with what has clearly become a culture of excess. I have to shut my eyes going around the city centre where all the nice shops of the past have turned into bars. All its all been done in the name of the shallow commercialism and dubious economic benefits of what I think is called “the night time economy”. Personally, I and most of my friends would not be seen dead in the city centre on a Friday or Saturday night when pure bacchanalia reigns.

I understand that the statue has something to do with some twinning arrangement we have or used have with the city of Dortmund in Germany and it was presented in exchange for the selection of Leeds United sportswear we gave them. I know this twinning must be seen in the wider context of peace and reconciliation which as a practicing Christian I am completely in favour of. Although where the Germans are concerned I must admit I struggle sometimes as a child born as the war was ending. I know Dortmund is a city which prides itself on their brewing but surely even they must see it has a downside.

Anyway time to go is all I can say if we are discussing statues which give out completely the wrong signals to our young and vulnerable.

How I do sympathise, Marjory. Leeds on a Friday night is thoroughly beastly. May I recommend you come across to Bradford instead, where an altogether more decorous night life prevails. I find I can walk the streets here of a weekend evening free from the fear that I am about to be humiliated by a gang of lasses in from Keighley poking fun at my sober and perhaps unfashionable wardrobe as they wobble pavement-overflowingly towards me along Boar Lane. But, meanwhile, what are we to do with the fat man and his beer barrel? Short of asking if Dortmund will have him back, could we perhaps allot another roundabout on the outer ring road to house him. In time we could relegate all the least-loved and most ethically-questionable statuary to the roundabouts and gyratories on the outer loop creating thereby a dedicated trail of artistic curiosities which would become an important element of the Sculpture Triangle and of the city’s tourism strategy. Admittedly this might bring traffic chaos to an already strained transport system as sculpture vultures dawdle along the A6120 and stop to admire.

Hello Chris

I’m sorry to say you have got one or two things wrong about me here. I am 76 years old and as a single pensioner going into any town at nighyt is not too appealing. I like a nice bit of tele in the evening with that nice Mary Berry, David Attenborough and of course the Antiques Road Show.

I do go out for lunch sometimes with my friends Edith and Maud from the Church but that is only for the “pensioners reduced price” at our local traditional fish and chip restaurant.

As far as statues are concerned I’m not sure what you are getting at here but it doesn’t sound like my cup of tea at all. You must understand that as one of Leeds’s Active Elder Ambassadors I have completely embraced the City Council’s and NHS Leeds’s “Inspiring our young – integrating our old” programme.

So obviously I would prefer statues of those inspiring individuals who have done so much recently to build this great city of ours.

I would suggest for your ring road sites – obviously the Brownlee Brothers. They are such nice young clean cut men without any of the whiff scandal which sadly taints so many of our celebrity sports heroes today.

For elderly representatives there are really too many to choose from as the city has advanced so much in recent years but clearly there must be a place for that much loved TV presenter Harry Gration who does so much to promote an authentic regional identity. Then there is Dr Kevin Grady, already honoured by the city for his celebration of Victorian values but even in retirement he remains such an elder statesman and role model. Finally I would suggest Liz Minkin former Kirkstall Councillor and mover and shaker in the Leeds Renaissance of those exciting Millennium years. A great loss to the city and the best council leader we never had.

I think statues like these inspirational figures would make Leeds even more inspiring than it seeks to be today.