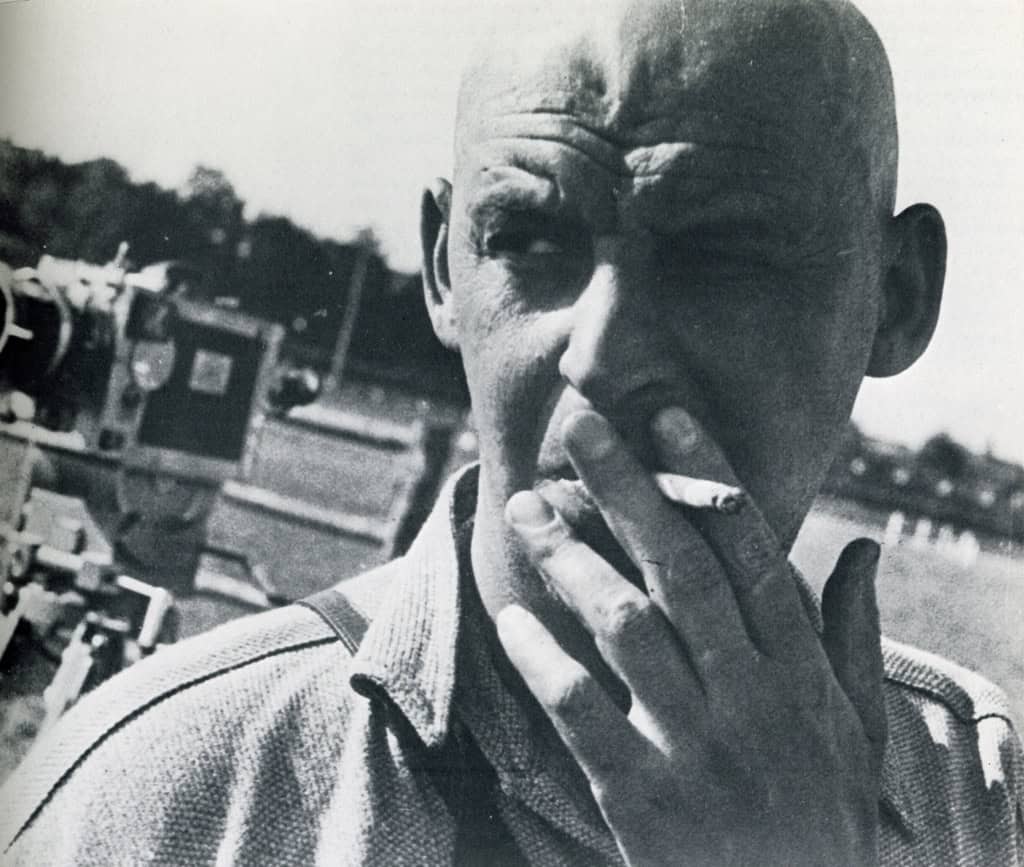

Alexander Rodchenko, pioneering Soviet-era graphic visionary, could have passed as a henchman in one of the Harry Palmer spy films. Intense and brooding, his face was a metaphor for his output as an artist: austere, unyielding, strikingly handsome.

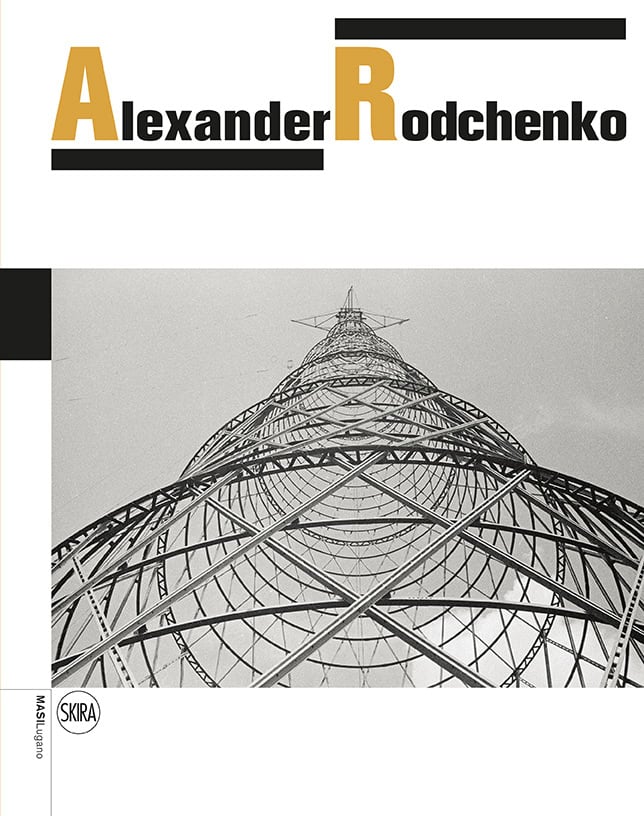

This fascinating book, published to coincide with a career wide exhibition of his photographic work at the MASI Museums in Lugano, Italy, offers a sense of light and shade: curated by Olga Sviblova, Director of the Moscow House of Photography, the original show went some way towards reclaiming Rodchenko from his rather fearsome reputation as an ideologue.

In the centenary year of the October Revolution – and with a major showing at the Royal Academy in London of Russian Revolutionary Art – SKIRA Edition’s weighty new tome on Alexander Rodchenko shines a timely light on a true innovator. The artist’s radical ideas may well have buttressed the visual lexis of commercial Capitalism – think of Peter Saville’s ground-breaking designs for Factory Records, for example – but it does not diminish his genius one jot.

Sviblova positions Rodchenko’s practice in the wider context of early twentieth-century avant-garde art, whilst holding onto the contradictory impulses of post-revolutionary Soviet Russia which shaped the uniqueness of his ideas. In 1924, already celebrated as a prodigious talent, Rodchenko was seduced by the immediate possibilities of photography, thereafter adopting it as his main tool of creative expression. In doing so, he signalled a ‘fundamental shift in photography and the role of the photographer.’ His first enlarger – weighing in at over 20 kilos and carried home through the Moscow streets because he had forgotten to borrow the rouble needed for a taxi – is the subject of one of numerous personal anecdotes in the book which gets at the man – son, husband, father, friend, mahjong obsessive – inside the undoubted iconoclast.

Rodchenko loomed large over Russian Constructivism, coining many of its slogans – the mantra ‘Our duty is to experiment’ was a particular favourite. A collaborative artist to his core, he remained faithful to this edict throughout his life, irrespective of prevailing political currents. It would cost him his reputation, as evidenced by attacks in the Soviet press which accused him of plagiarism; banned from exhibiting and expelled from the Union of Artists, it was not until 1957 – the year after his death – that Rodchenko’s photographic work was exhibited again, selected by his widow from among his extensive, meticulously catalogued – and largely ignored – archive.

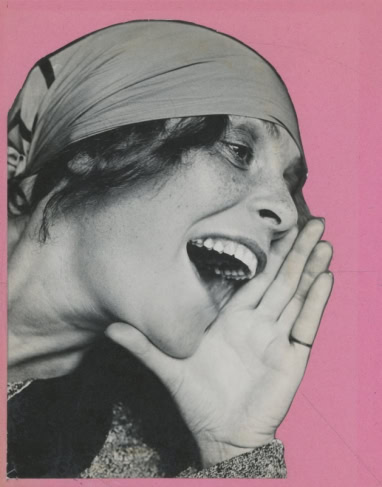

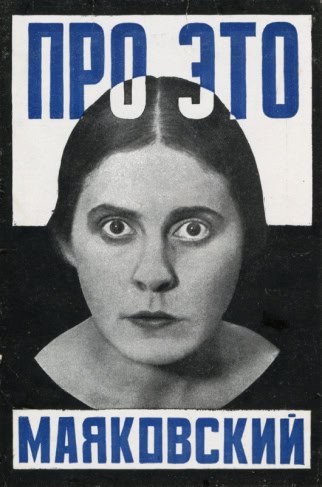

Much of that incredible archive is reproduced here, divided into movements like music: the brilliant early photomontages with which Rodchenko sealed his reputation; the photographic studies of family and contemporaries corralled as subjects for his ground-breaking graphic work, dubbed the ‘Rodchenko Method,’ with which he expanded the form; works of photo journalism, state-endorsed propaganda which still spoke of lives lived; the proto-punk illustrations created for a series of children’s books; dreamlike images of the theatre and circus, the final vestiges of ‘fantasy and imagination’ in Soviet Russia. ‘Value all that is real and contemporary. And we shall be real, not playing human beings,’ Rodchenko wrote in 1928.

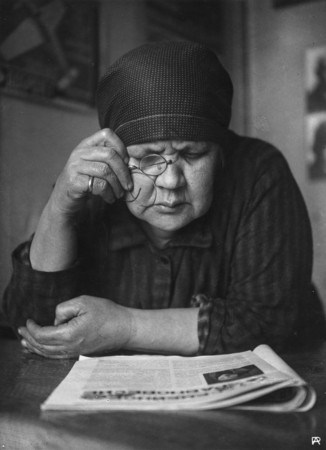

As one might expect, the book looks ravishing, exquisite; startling visual treasures are uncovered at the turn of every page, each demanding slow, methodical perusal and appreciation: an incredible portrait of the artist’s mother, for example, her features consumed in a reverie of concentration as she reads, begs due reverence. At their best, Rodchenko’s portraits are intimate and deeply personal, while at the same time they espouse a firm, universal ideological adherence to the state. This paradox is a recurring motif of the various commentaries which together calibrate the artist’s contribution to an acceptance of photography as an artistic and as an experimental form of expression. He would come to be defined by it: Varvara Rodchenko, the artist’s daughter, affectionately recalls that ‘he and his Leica merged into one and never parted right up to the end of his life.’

A piece entitled ‘Photography is an art’, written by Rodchenko in 1934 for Soviet Photo magazine, but not published until 1971, is a poignant reminder of the artistic vagaries of Stalin’s Russia. Criticised for being a formalist, Rodchenko was seeking to justify his photographic credo. ‘Art has broken free,’ he declared, expressing a genuine belief that society must foster a collective photographic experience. He suggested that photographic archives be created by the people for the people. ‘Photography has every right,’ he wrote. ‘It deserves attention, respect and recognition as the art of the present day.’

Consider these words carefully the next time you take a selfie.

Alexander Rodchenko (SKIRA Editions) is available via Blackwell’s Online here.

Neil Mudd is a writer and reviewer. He lives in Leeds. He wishes he lived in 1965. Follow on Twitter: @ANMudd