Who wouldn’t want to see a full sized Lighthouse erected in Holbeck, lit up and animated by all kinds of crazy, incredible, inventive projections and installations? Everyone loves a Lighthouse.

And if we could take a wrecking ball to Bridgewater Place and build the Lighthouse on a bank of rubble, broken window frames and splintered baffle boards, wouldn’t that be fabulous!… ah, we can but dream. Even if we win the bid to become European Capital of Culture 2023 some things will remain just a pleasant reverie.

The Lighthouse is just one of the many brilliant ideas in the Bid Book that Leeds will be sending to the ECoC judging committee in a couple of weeks.

I’d encourage everyone to read it. And, if you do, let me know how it ends. It’s not the most gripping of reads. When I got to the third bullet point in the second paragraph of the answer to Question 5C my attention started to drift.

But the point of the bid book isn’t narrative pyrotechnics. It’s not meant to entertain us Leeds people. The point is to cover the set questions the ECoC panel want answering, exhaustively, convincingly, and doggedly. And the Bid Book certainly does all that and more, leaving no box unticked, no subsection not thoroughly dissected, no bullet point not a shot to the head.

(If anyone is interested in the sort of things the ECoC judges are looking for and what characterises a winning bid I’d recommend this research document

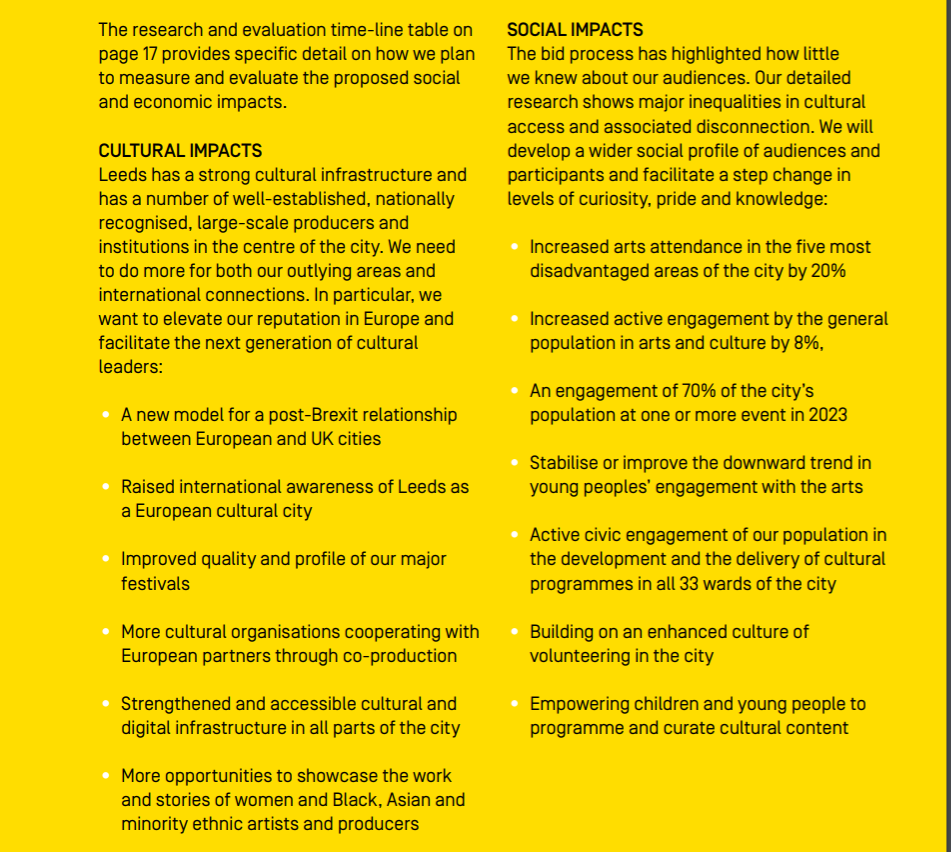

That’s what the Bid Book writers are up against. Graphs and pie charts, percentages and monitoring forms, evidence and sustainable legacy planning. Standardised evaluation criteria. Serious research. You can’t make this stuff up.)

The best part of the Bid Book – from the point of view of an ordinary punter from Leeds that is – has to be the creative programme. Jump to Question 12, page 28. Even the names of some of the events planned are wonderful; “Icing The Donut”, “Sew What?”, “Land Grab”, “Bus Pass”, “Baby Trees”. Not to be missed, any of these.

And I’ll certainly be there. Though as a non-dancing, non-diverse, non-member of any desirable demographic I won’t be doing much in the way of participating. My role will be strictly to sit back, put my feet up, and provide the applause. Observing. Which, in fact, is what I’m best at.

The only bit of the Bid Book that puzzles me is the social impact. Specifically, the maths. Numbers aren’t my strong point, I know, but I find it hard to work out how the numbers add up.

Leeds, as is pointed out from the start of the Bid Book, is strongly divided over the question of Brexit. We are a fifty-fifty city, which means half of us want to leave the European Union, and don’t believe in any of the ideology behind the Bid Book. Our ECoC 2023 bid is committed to the remain half. Absolutely and uncompromisingly committed. There won’t be a single event, artist, work, or show that will speak for the other side – even if the anti-EU artists, curators and promoters could be found, which isn’t likely. So, technically, can the bid be for the whole city?

And these numbers for increased arts attendance in the five most disadvantaged areas of the city, how will that work? These places have the most pro-Brexit voters. How will Europhilic 2023 events attract that sort of person? Or is 2023 aiming for the easier option of appealing to the Remainers in those areas, in which case that 20% figure is one hell of an ask! It’ll be more like 40%? Like I said, maths isn’t my strong point, but you get the drift?

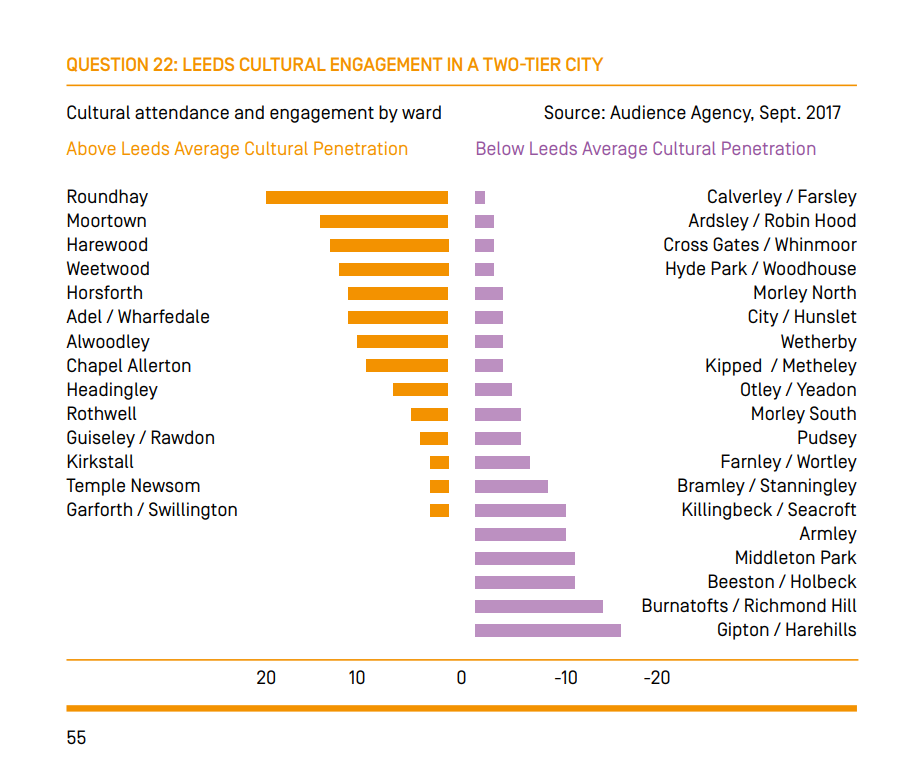

Here’s those five most disadvantaged areas of the city.

I’ve lived in four of those five areas and know them well (went to Junior School in Harehills, moved to Beeston in my early teens, went to High School in Middleton, and now live in Armley… I’m moving up in the world!) Unless you employed armed squads of cultural kidnappers to roam the streets of LS10, 11, and 12, cornering the odd confused local and shooting them with a stupefacient dart, before dragging them off to populate electrified pens at the back of the West Yorkshire Playhouse, I am a little sceptical of that 20% figure. I’d happily accompany any member of the 2023 team on a mission to the donut to show me how it’ll be done. I’ll even volunteer to load the stun gun. And can we start on Hall Lane? I can give you specific addresses.

That makes me sound cynical, I know, but I’m not. I genuinely would love it if Leeds had a shot at European Capital of Culture 2023. And, just to show that I have been thinking about it, here’s my own idea for a contribution to the cultural programme. I call it the Leeds Drum.

The biggest drum in the world, according to the Guinness Book of Records, was just short of 19 feet in diameter. I suggest Leeds builds a drum 23 feet in diameter (need I explain the figure?) And we build it out of discarded tin cans littering the parks of Middleton, Armley, Holbeck, Richmond Hill etc. We get teams of schoolkids to scavenge the cans and beat them flat. They then hand the flattened cans over to guys with garages and workshops who will cut, shape and solder the cans into usable sheets that will furnish the barrel material. Other collected cans will be sliced and flattened to make the drum skin. Some cans will be soldered end to end to provide internal struts for the sake of stability.

Rough estimates suggest that around 5000 cans will be enough to construct the drum.

The drum will be light enough for teams of locals to roll it around the inner ring road, given a police escort.

The drum will be stationed at various significant points in the city, starting with the Armley Gyratory, and everyone passing will be encouraged to bang the drum for Leeds.

Building the drum will have many positive benefits. The whole community can participate in collecting tin cans. Young people can learn vital skills from older people (soldering etc.) The public parks will be tidy. And everyone will get a good walk pushing the drum around the city.

All the bottom five districts of the donut will be the places that have the most participation (they have most of the cans) and this will increase civic pride as well volunteering.

Everyone, absolutely everyone, can bang a drum. Drums don’t discriminate.

And during Light Night the we can use the silvery skin of the tin drum as a perfect surface for projections (Dave Lynch will love it.)

Everyone’s a winner.

So, who’s going to help me put together a pitch to the Cultural Director of Leeds 2023?

Let’s bang the drum for Leeds!

Personally, I won’t be banging any drums, I will be getting out of town if Leeds wins the 2023 bid. The clamour of civil boosterists

for “this great city of ours” will be deafening, the demands to get involved insupportable and the urge to be inspired insufferable and exhausting.

I know I’m being selfish and inward looking here culturally I beginning to say enough already. If I want to bring my wife into town on a Sunday and use a disabled bay it is always best to check that there is not some sporting, charity or pop up event going on and the places have moved or are not accessible at all – mea culpa here I am a car user. My local

park is often used for paid events so this blocked off too. I prefer a quiet

private life to the insistent appeals that I join in an event (meaningless to

me) that is somehow attempting to bring the community together. Finally, if I want some cultural experience most likely it will be vicariously through the post (books) or via broadband (films). Lastly, being seen at posh events or seeing the latest something or other does not really cut it with my demographic.

It’s easy to criticise the bid as Cllr Dobson does as a waste of money which will do little to heal the wounds of a divided city. If you seriously wanted to do this you would look to more direct measures like building houses and schools, providing decent care to the elderly and services to youth. But LCC argues that this is not possible because of austerity – so now they have to encourage other more indirect ways to become the Best City – competitive and compassionate. So, let’s try a Capital of Culture bid. Now I don’t want to get party political as this is probably distasteful in our centrist city but nevertheless I think it is fair to ask some questions here.

The first question is does the bid itself represent anything more than opportunism or desperation in the face of austerity? I think that the answer lies in what is now a long- standing process by central government in the UK (since the days of City Challenge in the 1980’s) and to a lesser degree the EU (which usually relies on evidence based regionally aligned structural funding) in using competitions as a substitute for more rational approaches to delivering policies. Competitive divide and rule parochialism absolves governments from

their responsibility to devise equitable policies from which all cities benefit according to their needs and substitutes instead a wasteful process of failed bids and meaningless local rivalries. Leeds cannot escape this process but rather than amplify its negative effects by silly exaggerations – we have moved mysteriously from “the fastest growing city in the UK” to “Britain’s third biggest city” – perhaps a certain modesty of ambition would be in order, maybe a bid for UK capital of culture first?

I have a second set of questions around the way the bid has been planned, the assumptions on which it has been based and the aims it seeks to meet. Grand civic projects of the type the bid represents have largely been out of fashion in the context of declining city resources over the last 40 years. Perhaps not since “Motorway City of the Seventies”

has there been such an attempt to generate popular fervour around what is essentially a top-down exercise in central planning. Of course, the organizers of the bid would say that as an arms- length operation from the council they have done their utmost to build partnerships and engage stake holders but inevitably despite the claims to the contrary this is a project which is essentially one which is done to and for people in the name of benefits they may or may not ever receive.

In the bid “Culture” is inevitably pre-defined as something “other” since no bid could be based on a definition which sees culture in the truly inclusive sense of what everyone does every day. To this extent, despite claims that the bid is about “weaving” us all together to produce a more united community with economic benefits flowing outwards to the widest degree, the bid implicitly suggests there is some culture around which we can all coalesce or needs to encouraged and others which are too ordinary or too challenging to be acceptable. Quite where this boundary occurs is perhaps too difficult for the organisers to articulate.

To make the bid credible as a submission within this framework it builds on three major assumptions with which one might or might not agree – that the city lacks sufficient social cohesion, that the lack of cultural engagement or opportunity by some communities makes this worse and that the offer of more culture and its economic spin-offs will rectify this. Obviously, you can choose to buy into this or not but it is on the basis of the persuasiveness of these are the possibly tendentious assumptions that LCC is already investing millions of pounds.

More though these assumptions and the evidence used in the bid itself raise an unhealthy sense of old fashioned cultural colonialism and deficiency. The bid ranks communities according to the level cultural engagement creating in effect a hierarchy of need and lack. Perhaps the bid implies some sense of self -denial by these cultural reprobates who need in some way to be brought into the light and rescued from the darkness of their cultural deviancy – all very Arts Council circa

1967.

So, will it achieve its aims? Who will benefit and what will be the legacy? The bid is a clearly a political project that is too big to fail. If it is not successful in winning, it will be hailed as being successful in galvanizing the city and building and cementing relations between the Leeds’s cultural community. We will have a cultural policy of substance for the first time. If we win the gamble will have succeeded and millions of pounds of inward investment will be hailed, thousands of tourists will have been attracted and the international reputation of the city will have been amplified. A year of fun will have been had by all.

But, it will also be obvious who will benefit first and foremost naturally this will those who have put most investment into the project – the private sector and established arts organisations. Although there may be some disappointment expressed here that some of the funding has gone to national or international organisations hired for the prestige and wider appeal they have been seen to have brought in. The feeding frenzy has already begun.

I’m particularly intrigued by some of the site-specific works which illuminate literally in one case, areas of the city ripe for private house building or other land and property speculation – a long way from the real needs of those areas for social housing and community infrastructure.

Without dwelling on net costs to the tax payer, the sporting participation rates or the state of the site after the London Olympics I would go further back to my touch stone for the long- term success of civic cultural projects – The National Garden Festivals of the 1980’s and early 1990’s. Two are emblematic for me Liverpool 1984 and Stoke 1986. What were the legacies of these sites of spectacle? Well Liverpool’s lay derelict for many years and Stoke’s created the omni-present retail park and

a few offices. Value for money overall – questionable.

Will the gap between communities that the organisers’ identify as culturally well engaged and those identified as culturally deficient be bridged in the medium to long term? Somehow, I doubt this given the historic barriers which exist and growing diversity which may well create further challenges in the future. Personally, I think the city’s culturally elite communities will run off with all the pies and maybe this is the hidden intention since these are the people who are thought to create the wealth (but exasperate the inequality) on which the city’s

economy depends.

Finally, does Leeds deserve to win based on past performance in public policy-making? You have to laugh or cry. Mass transit – sorry only got the plans in after the money ran out: air quality – only after the Government forced us to act: devolution – against until it became the only game in town: PFI – now that’s one area of complete success as we are one of the most indebted cities in the

country: Homelessness – don’t give money to beggars: civic design – always enthralled of the private sector. Bid for European Capital of Culture – naturally only after the country votes to leave the E.U.

Culturally did we get a nice concert hall like the Sage, Bridgewater Hall or the Symphony Hall when all that Millennium money was sloshing around – no we got the more modest Millennium Square. Notably Leeds struggled to become the last city to get a major arena and immediately passed its management over to the private sector.

But we have history here – Manchester opened its art gallery after a major international exhibition in 1835, Liverpool’s Walker Gallery opened in 1877 and Birmingham’s city gallery opened in 1885. Last in line was of course Leeds in 1888.

European capital of culture 2023 somehow, I think not.