The milk-bars indicate at once, in the nastiness of their modernistic knick-knacks, their glaring showiness, an aesthetic breakdown so complete that, in comparison with them, the layout in the living rooms in some of the poor homes from which the customers seem to come seems to speak of a tradition as balanced and civilised as an 18th century town house. Girls go to some, but most of the customers are boys ages 15 to 20, with drape suits, picture ties, and an American slouch. Compared even with the pub around the corner, this is all a peculiarly thin and pallid form of dissipation, a sort of spiritual dry-rot amid the odour of boiled milk. Many of the customers – their clothes, their hair-styles, their facial expressions all indicate – are living to a large extent in a myth-world compounded of a few simple elements which they take to be those of American life.

See footnote.

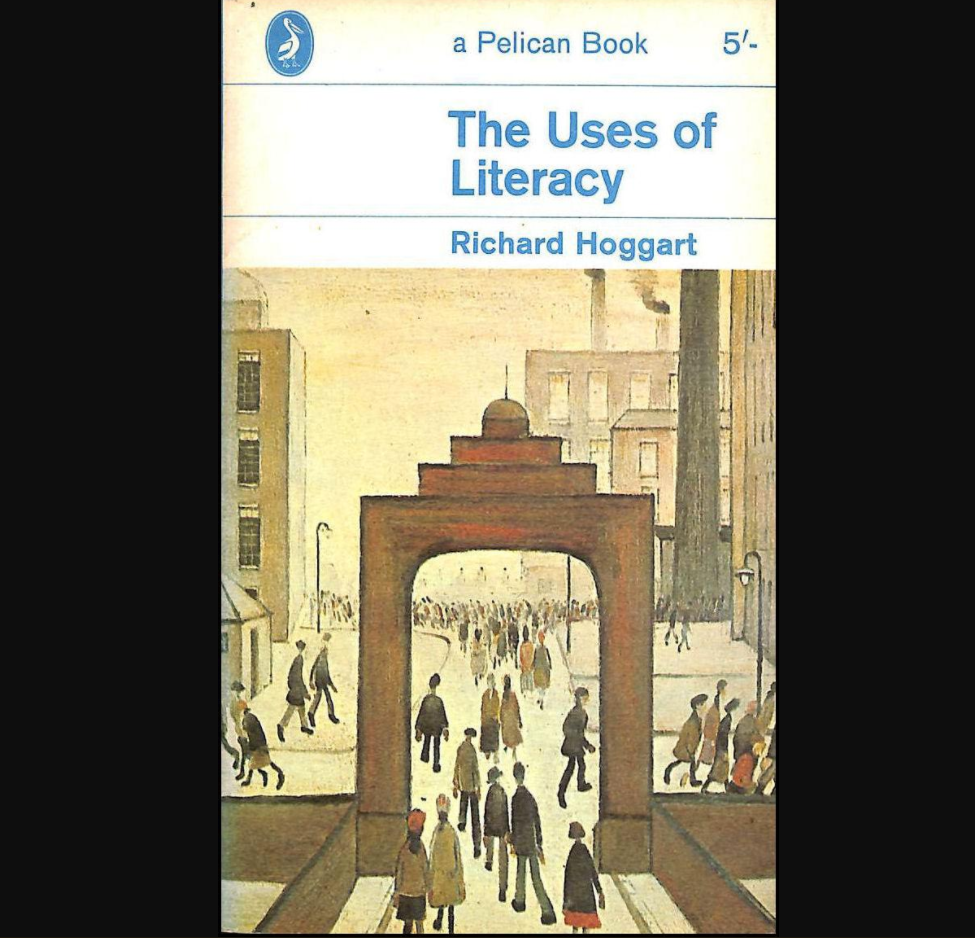

Richard Hoggart, brought up in Hunslet, teaching at Hull University, wrote this in The Uses of Literacy published in 1957. Like most post-war European intellectuals Hoggart believed the Americans should stick to making movies and gadgets and loans to bankrupt economies and leave the serious culture to chaps from the old world who knew how to do that sort of thing. American culture was, almost by definition, an aesthetic car crash.

The American government saw this as a PR challenge. They’d emerged from the war with a booming economy and a sense of cultural mission to match, and they could spend their way to cultural equality with the Europeans. And if any European intellectual or artist didn’t get with the program there were plenty of others who could be bought. The American “myth-world” was for sale and it was definitely a seller’s market.

One of the major instruments in promoting American cultural self-confidence after the war was the CIA. Founded on the 18th September, 1947, and mainly known for overthrowing democratically elected governments, running the international cocaine trade, conducting monstrous psychological experiments upon the native population, and bumping off the odd president (allegedly!) the CIA became, in the words of historian Hugh Wilford, “one of the most important artistic patrons in world history” (The Mighty Wurlitzer, p102). The impact of the CIA on post-war culture and art was so vast and deep that even here in Leeds you can’t escape it.

Take Henry Moore. Have you ever wondered why Henry Moore’s sculptures are synonymous with corporate capitalism, banking headquarters, global institutions and things generally iffy? Or why there’s more Moore in Chicago than Castleford? (Henry Moore in America: Art, Business and the Special Relationship, Pauline Rose.)The CIA had a lot to do with it, though not directly and in the open (they are a spy organisation. What else would you expect?) The commissions came mainly through “independent” funding bodies such as The Fairfield Foundation (known to many as the “Far Fetched Foundation” owing to everyone being in on the scam.)

The American state bought into Moore because he wasn’t a Communist (unlike Picasso.) Moore was Modernism minus the Marxism, a modernism that was comfortably numinous and reliably unpolitical. And unlike the restless Picasso, you knew where you were with Moore – he wasn’t going to shock you with doing anything new and challenging.

George Melly wrote a song containing the line, “no more, Henry Moore”, bringing attention to the fact that many people thought Moore was simply repeating himself, and made a documentary for the BBC in which he said that Moore’s sculptures were a perfect fit for a spy outfit (they could hide in the holes and conspire!) Moore’s links with the CIA were an open secret in the sixties and seventies.

The CIA also funded major arts institutions (board members including Herbert Read, whose personal library is in Leeds University) and cultural/political magazines, such as the famous monthly, Encounter (Cold War Modernists: Art, Literature, and American Cultural Diplomacy, Chapter 4, by Greg Barnhisel). Richard Hoggart was a frequent contributor to this entirely spy subsidised publication from shortly after he wrote The Uses of Literacy. Hoggart did not see this as an example of spiritual dry rot or unwanted American interference in authentic British cultural/intellectual life, however. Cultural Studies as a university subject was given a huge boost by American spooks.

The CIA also funded international social democratic political conferences attended famously by Hugh Gaitskell and Dennis Healy, both local MPs, according to Hugh Wilford in The CIA, The British Left and The Cold War; Calling the Tune.

Of course all this is a long time ago and far away. We are living in a very different era when nobody would fall for CIA propaganda any more. We know too much. We are too sophisticated. Too aware.

Still, I just got off the number 16 bus on Armley Town Street. On the side was an advert for a film called “Detroit” by the director Kathryn Bigelow, who made “Zero Dark Thirty”, a film about the capture and murder of Osama Bin Laden. You might want to Google that film.

Happy 70th Birhday, CIA!

Footnote

My dad was one of those young dissipated, slouching lads Hoggart was so appalled by. Here he is in 1957 with a couple of mates who’d just formed a skiffle band (talk about American myths!) Dad’s the one reading Melody Maker… or rather looking at the pictures. It’s upside down… Oh, dad!

Hello Phil

This is all very interesting but I wondered whether you were aware of what went on in Leeds during the Cold War from the other side of the “Curtain”.

By this I mean the activities of the East German Stasi spy Robin Pearson who was a researcher at Leeds University between 1979 and 1982. After that he was at Hull University 1984-87, York University 1987-88 and back at Hull 1988-89.

He was spotted as a potential spy while studying at Leipzig Karl Marx University in 1978. During this time he joined the East German youth organisation the FDJ.

His first job was to spy on other visiting students in Leipzig but his major task after his Leeds appointment was to spy on fellow academics and students both in Leeds and elsewhere in the UK with a view to finding about those individuals’ contacts in East Germany.

His basic brief was two fold. His first task was to establish any patterns of contacts between academics, student groups or others and the emerging dissident groups in the GDR and elsewhere in the Communist bloc. The East Germans suspected that some of these might perhaps be working for British Intelligence or even if they were not such intelligence might at least increase their local understanding of how indigenous protest groups operated. Polish studies and any links with Solidarity was one obvious target.

His second task was to second to identify academics, former students or others working for or in sensitive areas of the British state or international organisations who might be interested or pressured into working for the for the East Germans.

Long term the East Germans hoped his career in Leeds might enable Pearson himself to progress to for example a post in the British Foreign Office or possibly with an agency of the West German government.

Interestingly the local contact point with his handler was every first Tuesday of the month on the Town Hall steps by the lion on the left. Other meetings took place all over Europe under the cover of Pearson’s sporting career as a fencer.

By the time he left Leeds his brief had been widened to examine the University’s links with the People’s Republic of China. Under all these tasks Pearson write extensively about individuals and their work; the reports of which were passed up the chain to Stasi Centre and possibly onwards to Soviet intelligence. He was supplied with a camera and short wave radio to help his activities.

His activities were officially made public through research in the Stasi files in 1999 but there is evidence that his activities were known or suspected by both the security services and the BBC before this.

For more information read Anthony Glees’s The Stasi Files published by The Free Press in 2003.

I did not know this. I’ll have to look that book up.

Interestingly, noting your mention of China, the first Professor of Chinese Studies at Leeds Uni was Owen Lattimore. Joe McCarthy accused Lattimore of being the “top Russian espionage agent in the USA”. Which is why he ended up teaching in Leeds.