A little learning is a delirious thing.

Generally I come away from an artist talk at the Leeds Art Gallery – part of the Northern Art Prize program – a bit more aware what the particular artist is up to. Background, influences, inspirations, that kind of thing. The work on show isn’t always self-explanatory or obvious. I suppose I should be more clued up, or at least have spent a bit of time on Google before I make any judgements, but it’s useful all the same to have the artist in the room, in conversation, available for questions after.

James Hugonin began his conversation with Matthew Hearn last Tuesday evening with quote from a painter called Bryce Martin. I have to admit the quote went some way over my head and I was hoping for some kind of visual clue why this guy was important. No clue came. Subsequent internet surfing hasn’t revealed much either – apart from the fascinating fact that there are three Bryce Martins in some pokey little town in the Oklahoma panhandle. Which is not exactly relevant.

Then James passed around one of his notebooks and talked about his process. Each of his canvases is meticulously planned before a single spot of paint is added, before even the first coat of gesso is laid on . . . I wasn’t sure what gesso was or why eighteen coats were necessary, though Wikipedia has been helpful, at least concerning the chemistry of the substance.

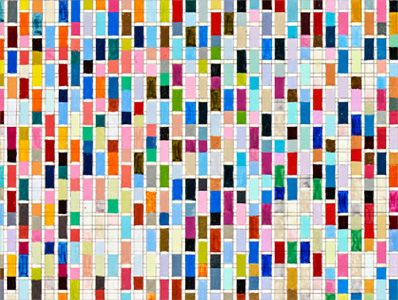

James showed a slide of a photograph of someone at work on one of his paintings in his studio. Then he held up a couple of transparent, rectangular plastic sheets that held some kind of regular pattern of coloured tiles (reminded me of the look of the cards that used to program old time machines like player pianos, that sort of thing.) James said these were a sort of template to guide his assistant in the correct placing of coloured tiles on the marked out canvas. I wasn’t exactly getting the whole procedure, or how the assistant interpreted the artistic intention behind the complex choreography that directed the arrangement of colour, though I do recall the numbers one and five and a half being terribly important somehow.

Finally James’s book was handed to me. Here was the code, the clue, the key that would unlock the secret. I would read and understand. For a couple of minutes I lost the thread of what James and Matthew were saying – though, have to admit, in my case the thread had gone a bit slack and ravelled a while back – and flipped through the first few pages. There was a lot of notation I noticed. Skip that, get on to the juicy bits, the part where James spills the paint pot and reveals what we’ve all be waiting for . . . I was half way through and my brain was befuddled by numbers and strange symbols and inexplicable signs. What was this all about? How was I supposed to grasp this? I could make sense of his notebook about as much as an ancient Persian grimoire or one of those things written by Machiavellian diplomats before the Enlightenment. I’d be a likely to crack the code as unravel the human genome.

As the conversation came to a close James reiterated that he saw himself squarely as a painter, and a painter is simply someone who works with “coloured mud.” He jolted me back to attention. Coloured mud I could understand. I could feel the pleasure and see the fun in playing with coloured mud. In the end all the notebooks, the algorithms, the persnickety rules for proper placement of individual tiles amount to nothing much more than a very elaborate game James is playing, simply for the joy of the play. When we are kids, before we lose the innocence of pure play, we delight in making up rules for games as we go along, changing the rules, complicating things, making the game harder, more demanding, endless. It seems as though James, thankfully, never properly grew up. Coloured mud is his element.

So when at one point in the conversation James went off on one about “discovering” something important when he decided to start a new piece at the right side of the canvas, I think most of us looked at the painting with a little incredulity. We’d never really have divined what he’d done or how he’d done it without him letting on. He could have started at the bottom, reversed the template and drawn the colours randomly from a bingo machine for all we knew; he could have hung upside down from a hammock spitting paint out of an ocarina humming the complete works of Morton Feldman for all I cared. It didn’t change my view of the work.

For me James’s paintings are records and embodiments of a playfulness that is rare in modern art. His painting doesn’t push any message, canvas any position, recommend any scheme for the general improvement of humanity. He’s refreshingly devoid of ideology. I’m not even sure if he’s “serious” . . . and that can only be a good thing.

I am not meant to say that I think James should win the Northern Art Prize. I’m certainly not saying he should win because of his persistence – as one Southern (ahem) critic facetiously put it. But if he did happen to win – and again I’m not saying that he should win the Northern Art Prize – it’s because he persistently reminds us that all art really is is playing with the coloured mud. And James Hugonin makes the coloured mud dance.