Guest blog by Sarah Cockburn

Open to the public from Saturday 19th March

Usual Museums Sheffield: Millennium Gallery visitor information applies.

Ruskin once described Sheffield as a ‘dirty picture in a golden frame’, mired in the grime of factories and slums but – like Rome – encircled by seven hills and – unlike Rome – the rolling majesty of the peak district. It was in this spirit of slightly patronising patronage that he set up a museum for the workers of Sheffield, with the express wish of removing them from the town’s smog to refresh their eyes and minds with the delights of nature and art. In Ruskin’s lifetime the museum was located in Walkley, later moving to a more central location on Norfolk Street before finding its current resting place as part of Museums Sheffield: Millennium Gallery.

Although the collection has been housed in the eponymous Ruskin Gallery for over a decade, it’s only with this refurbishment that it really comes to life. Previously the gallery’s opaque cladding – necessary to stop sunlight damaging precious paintings – kept even the most curious visitors at bay; and while it was full to bursting with an undoubtedly fascinating collection, this very crowding gave the impression of a bric-a-brac stall rather then an exhibition. However, a £200,000 refurbishment project financed by a major fundraising campaign and a variety of supporters has put paid to these deficiencies and resulted in a lighter, brighter and more eloquent presentation of the collection.

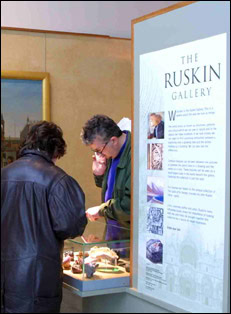

Setting just the right tone is the entrance, now open to view from the avenue and welcomingly curved, drawing the visitor into the more light-sensitive gallery beyond. On entering, a soft carpet and a rather splendid ammonite-inspired sofa reflect the rich colours and shapes that Ruskin so admired in nature. We then get to meet the man himself, or at least his bust, before having a rifle through his desk in an interactive segment reminiscent of the Pitt Rivers Museum, or more recently The Wellcome Collection, where a visitor’s curiosity is piqued by a temptingly half-open drawer. Next we are introduced to Ruskin’s key interests – art, nature, geology and architecture illustrated by a pleasing eclectic collection of objects. This treasure trove includes a beady-eyed stuffed flamingo, beetles and butterflies displaying the most vibrant rainbow of colours and glittering crystalline quartz. These natural objects sit next to art objects which echo their colour or design – a book embossed with peacock feathers, jewel coloured illuminated manuscripts and, even more directly, an exquisite horn made by Andy Goldsworthy out of dried leaves and thorn in a remixing of nature’s own craftsmanship.

This synergy between art and nature was Ruskin’s dearest concern encapsulated in one of his most famous quotes, ‘There is no wealth but life.’ It’s not unfair to say that he was more skilful with words than with a paintbrush and although his many sketches and paintings on display speak of a passionate interest in his subject, they pale in comparison to neighbouring work by JMW Turner and John Wharlton Bunney. This is why Ruskin is remembered as a critic, a thinker, a philosopher rather than an artist. His writings are echoed in this collection, reflecting a wonder for the natural world, an admiration for beauty and a curiosity about humanity. These concerns speak feelingly to The Ruskin Gallery’s neighbours, the foliage of the Winter Gardens, the intricate designs in the Netalwork Gallery and especially the exhibition Graphic Nature currently displayed in the Craft and Design Gallery.

The deliciously overwrought BBC drama Desperate Romantics might have painted the great man as a manipulative patron and an impotent husband with a horror of pubic hair, but the Ruskin Gallery refurbishment shows he still has plenty of worth to say.