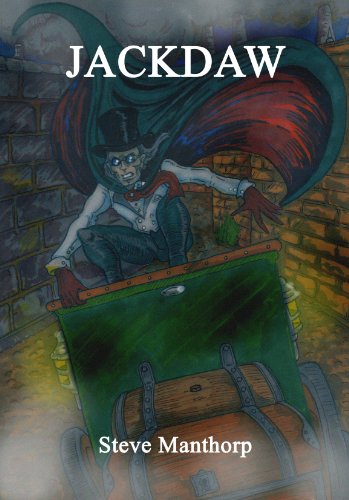

Ivor Tymchak gets his reviewing goggles on and wades into Steve Manthorp’s new steam-punk fantasy novel, jackdaw …

Steve Manthorp has written a novel – a fucking novel! Congratulations Steve, that’s a lot of work and you have my respect.

But wait, you probably want to play with the big boys, don’t you Steve? OK, I’ll calibrate the base measure of my review against ‘published’ novels that I’ve read. Here goes …

The first few chapters of Jackdaw made me think that Steve had written a graphic novel without bothering with the graphics. The story is set in the 1900s and has a cast of steam-punk characters who bestride the pages. They indulge in a series of unrealistic fight sequences that result in the loss of a docklands warehouse and the deaths of two people without so much as a raised eyebrow from anyone. The police are on hand to fish people out of the water but they are more interested in the reputation of the novel’s hero, James d’Orr and his moniker of ‘Jackdaw’, than to investigate the cause of the fire.

This type of thing is acceptable in a superhero comic but I expect a bit more rigour from a full novel. It all depends on how you like your stories I suppose, I like mine with rules tied to the basic laws of physics and to have characters who follow rational human behaviour – Jackdaw struggles somewhat with these criteria. For example, d’Orr seems to lack the common sense of not allowing himself to fall for being left alone with a couple of unsavoury characters in a deserted warehouse immediately after he has just publicly exposed them as charlatans. And we’re supposed to believe that he is a quick-witted detective?

The graphic novel clunkiness shifts into a smoother gear when the narrative moves into the main storyline involving an heiress, a family estate and secret tunnels. Steve is too preoccupied with the descriptions of his characters, however, rather than the momentum of his narrative. Although some idea of appearance is useful, the requirements of the narrative are more important and too often I found myself hastily reading through the descriptions – competent though they are – in the hope of coming across some much more necessary story or plot.

When these did arrive I found myself slightly annoyed at the cavalier attitude to detail. At one point for example, d’Orr is kicked into a subterranean pool of scalding hot water whist dressed in old Victorian clothes and possibly a cloak. Several hours later, after more damp adventures in the labyrinth of tunnels (through which he navigates his way using a box of perfectly useable matches even though they had earlier entered the pool with him) he emerges in a church crypt and subsequently has tea with the vicar. Presumably he is still dripping wet and has blisters emerging all over his lobster red skin? Common sense dictates that a change of clothing and the application of bandages would be required before accepting an invitation to sit in a leather chair and enjoy a civil cup of tea with a member of the clergy.

There was also one comical moment in the book which I’m not sure was intended. There is a sexually charged scene where d’Orr – who is skinny and has to wear blue tinted goggles for his photophobia – and the heiress exchange a passionate kiss. The involvement of d’Orr’s goggles in the embrace made for some mental slapstick in my mind.

It was only halfway through the book that the story started to come together and engage me. Enough of the basic building blocks of characters and motives were in place for intrigue to inhabit the pages and to drive the narrative along. But then Steve gets carried away with his fictional invention and the grand sweep of his canvas and in all the frenzied action the attention to detail gets abandoned. I’m not being churlish; it is attention to detail that makes the bigger picture loom more real in the reader’s imagination. The finer structures of the story have to stand on solid foundations. I mean, I’m no engineer but even to my mind, six inches of rock sounds totally inadequate to hold back thousands of tons of water. In the tidal wave that ensues we have no mention of d’Orr’s spectacles and yet earlier in the book it is frequently described how he painstakingly removes or straps them on depending on the circumstances he finds himself in. With a tidal wave it is reasonable to assume that they would have been ripped off his head and yet it is only much later as he surveys a scene above ground that the spectacles are mentioned and we learn that miraculously they had remained on his face all the time he was struggling in the torrent of scalding water.

Time also seems to pass at a different rate in his novel than the rate I am familiar with in real life. Miraculous actions – which would normally take weeks of practice – are performed in an instant (OK, I accept, it’s a ripping yarn, but still …) – and complex manoeuvres, which should take several seconds, are squeezed into the blink of an eye.

Steve has clearly researched the artefacts from the historical period in which he sets the novel. This feature could be made more of in future novels (I believe Steve is writing a sequel), as some of the revelations are truly surprising. The bicycle lamp is a case in point. At first I assumed that some kind of typo when he described “pumping” the lamp, but of course, there were no handy batteries in 1901, it required a different process.

Equally interesting were the descriptions of work practices used in industry at that time. A detailed look at the dying process during a tour of the mill by d’Orr produced the memorable sentence “A dying breed.” Unfortunately, there weren’t enough of these kinds of descriptions and insights in the book. This aspect of the story reminded me a little of A Short History of Tractors in Ukrainian by Marina Lewkyca in the way it interwove segments of history into the storyline. More should be made of this device in future novels.

In his dénouement of the mystery Steve goes down the ‘with one bound he was free’ route. We even have the classic ‘evil villain explains to the tied up heroine exactly what his motives are while we all listen in’ scene – something which has been lampooned by many a comedy sketch. If you like James Bond movies with all the plot holes and improbable stunts then you’ll probably like this book.

Despite its flaws the book is well written and shows plenty of invention (I was already aware of his talent through his imaginative and clever Bettakultcha presentations). I can only assume that Steve is finding his voice in his writing, trying things out and seeing what works.

As with his presentations, Steve clearly enjoyed himself writing the book and this comes through the prose. It is also clear that he is serious about the craft of writing. It is going to be interesting to observe the progress of his writing as his prowess improves.

One to watch.