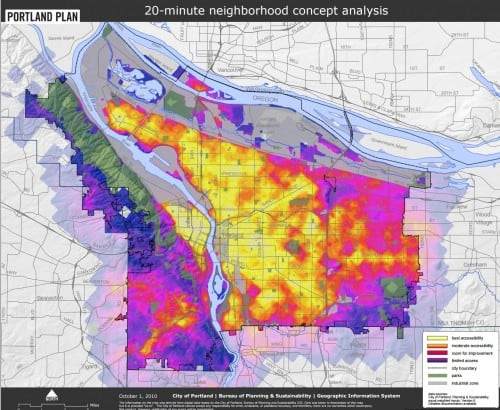

The idea of the 20 minute neighbourhood was developed as part of the Portland plan and is based on the idea that you can get all of the daily goods and services within a 20 minute walk of your house. There are variants of this as the concept is used by a variety of people, promoting cycling, walking and high density development. There are also a variety of ways of measuring liveability and walkability, the latter can give you the 5, 10 or a more precise number of minutes that your neighbourhood can deliver shops, exercise, school, library etc.

It’s probably true that before cars the majority of people had a less-than-20 minute neighbourhood, and for many that included their journey to and from work. In fact where I live in Armley in Leeds, most of the housing stock was created for workers at Armley Mills. The housing is on a close grid system and is highly permeable with back alleys, and there is still a fair amount of green space, which includes common land held in trust for the people of Armley as well as the council parkland. The density is probably partly a product of keeping the distances low, and the costs of construction down; when the terraces were built the occupancy was far higher than it is now, with some families living in one or two rooms. Armley also has its township centre with a library (built 1901), a leisure centre (the original Armley baths dated from the 1920s) and shops. Currently there are quite a variety of food shops, a butchers, household things shops, charity shops, a post office, banks, cafés and a large number of take-away, betting shops and quick-cash shops.

One key part of the 20 minute neighbourhood is that it should be a place that invites people, so that they choose a walk to their amenities, and this is perhaps where Armley fails in some regards. For many people their walking experience is next to or crossing heavily trafficked roads and it is much easier to drive to Armley than to cycle. In balance the bus service is good, but subject to congestion delays. Leeds has a number of townships like Armley but arguably, in my view, the most close to a 20 minute neighbourhood is Chapel Allerton. For me, London is the ideal place to experience the 20 minute neighbourhood. The high density and low car ownership within central London means that you are seldom far from a shop or school as well as cafes hairdressers and a whole lot more. Research also shows that people that walk and cycle visit the neighbourhood shops more often and spend more than people that drive.

One question that I have begun to ask is ‘how is it that we ended up moving away from liveable and walkable communities?’ Although car ownership is a contributory factor there are larger forces at work, many of which we imported from America in the 1950s and 60s. Perhaps the worst is the combination of suburban housing estates and zonal planning. Zonal planning is still very much alive in Leeds, where areas are classed as ‘light industrial’, residential, offices etc. When I googled zonal planning Leeds the first hit was for the Thorpe Park development on the junction of the A63 and M1. Business parks and out of town shopping centres are one of the most horrible outputs of zonal planning, these by definition are not where people live and built mainly for people to access in cars. Its very simple really, if you plan a residential zone, office park, a retail park, and make it so that they are most accessible to cars with large car parks then it’s not surprising that people drive to them. Zonal planning also tends to only build walking routes along the roads and places the zones in pods with no direct walking or cycling access. The planning is also very formulaic so that roads, planted areas, trees and the buildings are often repetitive and featureless. Walking is pleasureless and too often you have to wait to cross traffic, or try to navigate massive and unfriendly car parks.

Although the nails are now firmly in the coffin for new out of town shopping centres, a number of policies have meant that few can get about their daily lives without a considerable amount of travel. Injecting choice into the school system has meant that often children don’t go to their closest school, and families often move to an area in the catchment of their chosen school, particularly for high schools. Armley for instance sees a steady outflux of aspirational families with children in the final years of primary school.

One thing that is alerting interest is that successful 20 minute neighbourhoods can attract high value industry. For instance, in London, Bermondsey and Shoreditch have become very attractive for creative and dot com industries. There is a growing body of evidence from America that denser cities with less car parking are more economically succesful, so far this has made little impact in the UK.

20 minute neighbourhoods should be far more inviting to walk or linger for a chat, or for us to indulge in people watching and to make this we have to improve the streetscape, or what planners call the urban realm. One of the characteristics of suburban development and zonal planning is the lack of urban realm. Although suburbia cultivates the ultimate in private realm with nice gardens and plenty of space inside the house, the streetscape is boring and often so dominated by cars and the roadway that it is unsafe to walk or cycle. You don’t have to go far around Leeds to find many estates with very few shops or amenities and a boring urban realm.

My worry is that unimaginative housing developments of the type are what a being planned for Leeds, estates that few will want to spend time in, and instead spend their time clogging the distributor and arterial roads with trips to fulfil needs that could have been met locally. What kind of Leeds do we want to create in the next 15 years? More sprawling estates with few amenities or more higher density townships with mixed use developments. Urban living in the centre of Leeds has grown massively and there is even a new secondary school planned for the centre of Leeds. Young people increasingly chose to rent and live in 20 minute neighbourhoods, and also are delaying the age that they own cars and learn to drive. Places where these people can meet and chat are a hive of creativity and will develop new industries and ideas. Suburban estates where people remain in their own houses and gardens do little to generate new ideas and high value businesses.

This blog reminded me of an essay about walkability and GIS that I completed for my Masters. I managed to dig it out this morning! The conclusion was pretty much what you say here – I’ve pasted below an extract with some references to academic papers which provide the evidence. In suburban Horsforth my neighbours only ever seem to walk when walking their dogs and drive for every other journey…and sometimes they drive their dogs somewhere to walk them. Boring and monotonous residential streets hardly encourage walking.

We have seen that walkability is a subject of interest to urban designers, town planners and public health professionals as well as the transport field. So what role can GIS play in measuring walkability and planning walkable urban environments? GIS as a quantitative spatial analysis tool may not be the most appropriate tool to measure and analyse subjective elements of walkability such as urban design and the cultural elements of encouraging people to walk. It has, however, proved a useful tool in measuring walkability in terms of access to services and facilities in local environments.

Several studies (Bentley, Jolley and Kavanagh, 2010; Frank et al, 2006; Leslie et al (2007); Owen et al, 2007) have used GIS to ascertain whether the presence of four environmental attributes found to be related to walking: dwelling density, street connectivity, land-use mix, and net retail area has an impact on levels of walking by the local population. Compiling information about the presence of these environmental attributes into a GIS database enabled a walkability index to be derived. Each neighbourhood was given a walkability score based on the environmental atrribute data contained in the GIS database which enabled a comparison of measured levels of walking in neighbourhoods against their walkability score.

Overall, the studies found higher levels of walking amongst the local population in areas where there was a high presence of the four environmental attributes related to walking. Having a variety of destinations linked by a dense network of paths close to the road was associated with more time spent walking (Bentley, Jolley and Kavanagh, 2010). Owen et al also found that people who lived in more walkable neighbourhoods (i.e. with high scores in the walkability index) walked more often, possibly replacing car trips due to the proximity of shops to residences. However, Frank et al (2006) noted that people may wish to lead an “auto-oriented” lifestyle, regardless of whether their neighbourhood is walkable.

Although the walkability index generally corresponded walkable areas with higher levels of walking, issues of self-selection (people choosing to live in an area because they perceive it to be walkable) (Bentley, Jolley and Kavanagh, 2010) and self-reported information on walking levels (Frank et al, 2006) were identified.

Leslie et al (2007) noted that levels of walking were not always related to density and connectivity – some lower density suburbs characterised by cul-de-sac streets also had higher walking levels due to a pleasant and well-connected pedestrian network. In general, higher density grid pattern street layouts are more walkable (See Figure 3). This emphasizes the importance of using GIS-derived data as a part of a toolkit that includes local knowledge rather than relying on it in isolation (Schuurman, 2004).

Bentley, R., Jolley, D. & Kavanagh, A.M. (2010) “Local environments as determinants of walking in Melbourne, Australia”, Social science & medicine, vol. 70, no. 11, pp. 1806-1815.

Leslie, E., Cerin, E., duToit, L., Owen, N. & Bauman, A. (2007) “Objectively Assessing ‘Walkability’ of Local Communities: Using GIS to Identify the Relevant Environmental Attributes”. GIS for Health and the Environment: Development in the Asia-Pacific Region, pp. 90-104.

Owen, N., Cerin, E., Leslie, E., duToit, L., Coffee, N., Frank, L.D., Bauman, A.E., Hugo, G., Saelens, B.E. & Sallis, J.F. (2007) “Neighborhood walkability and the walking behavior of Australian adults”. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 387-395.

Frank, L.D., Sallis, J.F., Conway, T.L., Chapman, J.E., Saelens, B.E. & Bachman, W. (2006) “Many Pathways from Land Use to Health”, Journal of the American Planning Association, vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 75-87.

Schuurman, N. 2004, GIS :a short introduction, Blackwell, Oxford.

Thanks Ian, I’d forgotten about the phenomenon of driving your dog to take it somewhere for a walk, its not dissimilar to putting your bikes on the back of a car to go for a cycle, and is an indicator of the type of urban realm that we’ve designed over the last 50 years.

I’ve just picked this from some data in Melbourne which adds a station angle to the topic…

http://www.propertyobserver.com.au/forward-planning/40498-encouraging-walkable-neighbourhoods-is-about-more-than-proximity-angie-zigomanis.html#.VQwIuMBMGXh.linkedin

Pete

The 20 minute neighbourhood heh – one can dream ! The thing that confused me most though, when I moved here was the preponderance of pavements that stop suddenly in mid journey forcing a tramp over mud at best, or pushing a pram/wheelchair into the road. I’m not sure why 1960s town planners felt that anyone would want to walk half way up the hill to nothing more than a grass verge, then go no further ! Here on the outskirts of North Leeds we have few facilities: a Dr’s surgery that is threatening to move 2 bus journeys away, a supermarket that has purposely and systematically closed down every other shop in the district centre, one naff pub, half hour walk to nearest post office, similar to nearest bank, a council office that’s moved to the far side of Horsforth, which might as well be another town. But hey, we have a new sports centre so that’s ok. Bus services are good, but it’s a 30 minute journey to the nearest place with facilities (taking into consideration the walk to, and the wait at the bus stop). I don’t really mind all this, because, although I didn’t exactly chose to live here, it’s nice being right on the edge of town with views of fields and hills from my window. I would say the biggest problem is the services that never reach the outskirts of the city (specialist clinics, advice centres, and so on). An assumption that living in such a salubrious post code area (even though actually, most of us live on the council estate) means everyone has cars I suppose . Nearest services are across town in places you need 2 buses to get to. As-the-crow-flies distances are of no use to a public transport user. I’ve sat through too many meetings with NHS managers who think that moving outpatient services to St James isn’t a problem, because they cannot get their heads round – “I’m ill and I’m stressed about being ill, and I have to get a bus into Leeds, then another bus out of Leeds to Harehills which is probably close to 2 hours journey, to see my consultant, then another 2 buses home again”, because to them it’s a quick drive there. The 20 minute neighbourhood is an interesting concept, but I’d settle on services 30 minutes away by bus.

Hi Becky

i feel your pain… I think footways (as they are professionally known) are usually provided as developments continue outward from the edge of the city if you see what i mean. They are usually part of a section agreement with a developer so provision is willy nilly and not strategically done. Its all very well in the city centre where things are dense but as soon as we get out to the periphary of cities we are left with just the roadway and a verge, even though the verge is often owned by the highway authority. What we do need is more walking audits to point out where the pedestrian environment falls short. I think the magnitude of the problems are a bit mind boggling, but we have to start somewhere.

Usual stuff for the able bodied middle class

To fit in with this utopia I’d be only too happy to push my wife in a wheel chair for 20 minutes if I didn’t have COPD.

Obviously I would be happier with better pavements (sorry I mean footways -oops another able bodied misstatement)- but realistically even in the 20 minute city I’m either going to

have to have stuff delivered (BRRRR BRRRR – socially isolated pensioner alert)

take us both in the car (or dear more CO2, perhaps at my age I need another test)

or get the council to provide a couple of mobility scooters (and risk becoming a footway blocker to all those youngsters training for a charity run)

This kind of urban design which thinks so narrowly “only for people like us” is really no different from the 60’s modernist planners they so frequently criticise. It just likes to pretend it is.

Basically it just makes me

Sour