John Atkinson takes a trip back in time on the streets of Bradford …

Stood outside Bradford’s famous Sweet Centre, we gathered. Earphones in, a countdown to pressing ‘play’. 3-2-1. Music. Fantastic, beautiful, ethereal music. Reminiscent of a timeless Catholic classic, maybe Ave Maria, the Leipzig Synagogue Choir gave us Towau I’Fonecho. I didn’t know the piece yet I recognised it; it was strange and familiar all at once – and as such, the perfect introduction to a walk that would take me to places I know so well but presented, gifted, in a new, special, unusual and beautiful package.

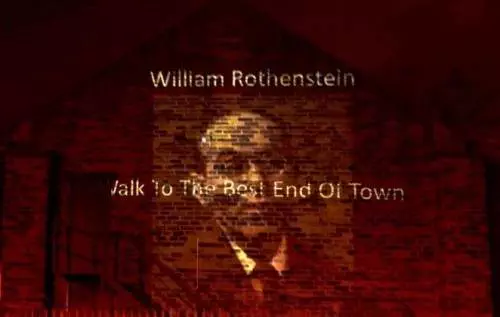

We stood and I wondered for a second why we’d passed the ornate entrance to the Bradford Reform Synagogue until I saw a figure in the darkness. Sharp suit, trilby hat, smoking a cigarette and looking at his pocket watch, he was familiar yet strange, looking entirely different to all those who passed him yet demonstrably he belonged. He was to be our guide: Sir William Rothenstein, artist, merchant’s son and Bradfordian who grew up in Manningham when it was the best end of town.

“I was just about to take a wander along Manningham Lane; would you care to join me? I could show you around the best end of town,” he offered, and we gratefully accepted and set off down Bowland Street to see the fashionable quarter of the great manufacturing centre that was Bradford in 1903.

‘Walk to the Best End of Town’, a specially commissioned immersive tour of Bradford as it is and as it was, was created by oral historian Irna Qureshi who produced something so much more than a walk and talk. Interweaving Jewish music and Rothenstien’s commentary, we were forced into a state of blissful cognitive dissonance: Sir William extolled the virtues, beauty and wealth of the streets we tramped, but eyes told a very different tale.

A procession, deaf to a century’s progress, blind to our guide’s tale, we walked on to Belle Vue Bazaar, hearing tales of the finest Hamburg smoked beef, German sausages and chocolates, and foreign cheeses, but seeing signs for Polish goods and Asian spices; we heard of royalty and nobility ordering fancy clothes, and saw saris glitter green and gold in windows – maybe Manningham hasn’t changed so much after all.

A tram passed our ears; cars flashed past our eyes. Sir William told us of the grandest houses in the city, taken by rich merchants, many German Jews, who flocked to Bradford to make their millions and create the wealthiest city of the time by forcing forward technology and selling silk and worsted wares to the world. The grandest of houses, tiny enclaves for the super-rich, were set back for the road to keep the riff-raff of the lower middle class from the door; now, their driveways provide ample parking for cars and vans from Poland, Lithuania and Latvia. The merchants may have come and gone but their ghosts, their footsteps, can still be heard in the long, curved terrace of Apsely Crescent, in the servants’ quarters fashioned into cheap bedsits, and in names like Blenheim Mount, Heidelberg Road and Hanover Square.

It’s the architecture of the poor which most fascinated me. The streets made for the millworkers, houses back-to-back, two up and two down, show the care we used to take, building homes not just houses. The lintels and doorways of every street changed from the last, becoming less or more ornate; tarmac gave way to cobbles and returned, and the streetlights suddenly became those Sherlock Holmes studied clues by. Each street had its own character and was joyfully ignorant of uniform estates. What businessmen were these who forwent profits in favour of soul?

At Lister Park, we passed under the illuminated gaze of Samuel Cunliffe Lister, one of the greatest men in Bradford’s long and distinguished history, and promenaded through his family’s former estate. Cartwright Hall, a rich golden glow in the night, stands as a monument to family’s wealth and benevolence, and under a streetlight we saw our guide, Sir William, painting a scene. He bemoaned his city’s lack of interest in his works and he’ll be glad to know that Bradford has since purchased a number of his canvasses which can be seen across the district, as well as in Parliament, The Ashmolean, and various universities including Oxford and Harvard. We couldn’t disturb the artist at work, though, and moved on to the simultaneously upbeat and haunting Klezmer Lounge Band.

A long snake of oftcumeduns, wires hanging from our ears, we couldn’t have looked more out of place if we were wearing trilbies and checking fob watches. We were asked a few times what we were up to: a group of friendly urchins, as Sir William may have put it, trundled up and asked if we were tourists or historians – I didn’t really know. A bloke walking his dogs cast his mind back 30 years when Manningham was a different place, a richer place – I told him it was the best end of town in 1903 and, we agreed, in many ways it still is. A couple of blokes on their way between two pubs talked animatedly of history and culture in accents as thickly Bradfordian as any Victorian millworker, though maybe Sir Titus Salt wouldn’t have enjoyed their post-work proclivity. In those seconds, I felt intensely grateful to be a Bradfordian on a walk through the best of town.

Sir William interwove Bradford’s history with his own, talking of the noise and industry of Drummond’s Mill, the benefits to the lower middle class lifestyle and the workers’ lungs of Manningham Railway Station, the charity of the great and the good in building Bradford Children’s Hospital, and the boredom and punishment of being schooled at Bradford Grammar. Irna Qureshi interwove dialogue with music and an amazing soundscape of Bradford’s past, with the noise of the Manningham Mill becoming louder and louder as we approached, audibly demonstrating the industry and technological revolution the area was famed for.

Passing once again another of Bradford’s icons, The Sweet Centre, we turned into Bowland Street to see the side of the synagogue transformed. The Leipzig Synagogue Choir serenaded us as Sir William’s canvasses were projected, 30 feet high, on the wall. The music rose and fell, the words unintelligible whilst speaking volumes. Then, a perfect symbiotic crescendo: the music lifted as an old film of a tram ride up Manningham Lane exploded into life. My heart sang and my jaw dropped.

The crack of applause burst the bubble and we were back in the modern day. We hadn’t spoken all the way round but before the chatter, in silence, I watched a couple hug, and another, and another… and it was only then that we found our voices. We stood in the cold and babbled about our best bits – the mills, the cobbles, the sounds, the sights – and right then, right there, on Lumb Lane in 2012, we were in the best end of town.

The concept of an oral tour of a place so changed by time and circumstance was perfect for this walk. A purely historical walk, with a modern speaker saying ‘This was this and that used to be that’ simply wouldn’t have had the impact, the gravitas this walk walked held in spades. Walk to the Best End of Town gave me an understanding of Bradford as it was, an appreciation of how the city’s changed, and an admiration for one of its residents I’d never heard of before. The music told us story after story, and our guide bared his life and soul, and that’s why, at the end, we embraced, we smiled, we even shed a tear.