‘It seems to be freighted with overtly symbolic meaning, Sheriff!’ warned the librarian… Glen Baxter

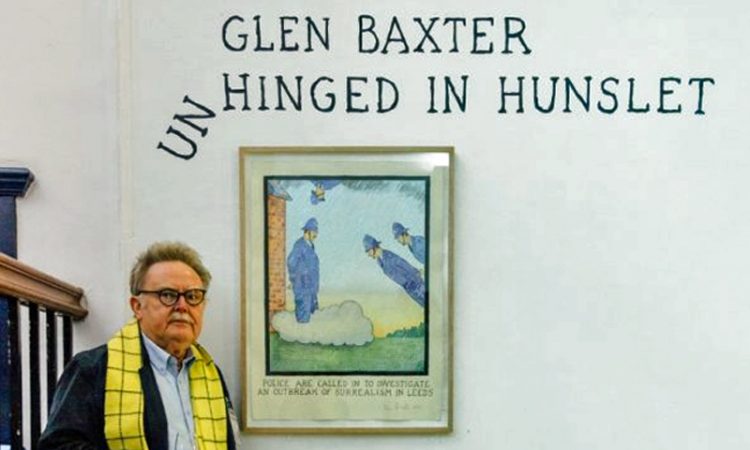

Revered in France, featured in The New Yorker and born in Leeds, artist GLEN BAXTER’s first ever exhibition in the city has just opened at the Vernon Street Gallery. ROBERT KILNER takes a stroll with the artist.

Glen Baxter‘s Artist Talk is in the style An Audience With…, like Billy Connolly and Shirley Bassey used to do. He’s as entertaining at the lectern as he is on paper. After a brief history of Dada and Surrealism he talks about growing up in Hunslet and the various influences that shaped him. He’s a great raconteur, and seriously funny.

The artist has returned to Leeds for Unhinged in Hunslet, an exhibition of his prints and drawings at the Vernon Street Gallery. Incredibly, it is his first one ever in the city where he was born.

Baxter grew up in Hunslet, an area that’s been cut and pasted more times than a Max Ernst collage. The river was moved in the Middle Ages and the town scoured in the sixties to make way for acres of A-roads and motorways.

He doesn’t return much, but says his wife, who’s got a better memory, recalls coming back from London and seeing the old flagstones outside The Railway Tavern being tarmacked over ‘to make it all modern.’

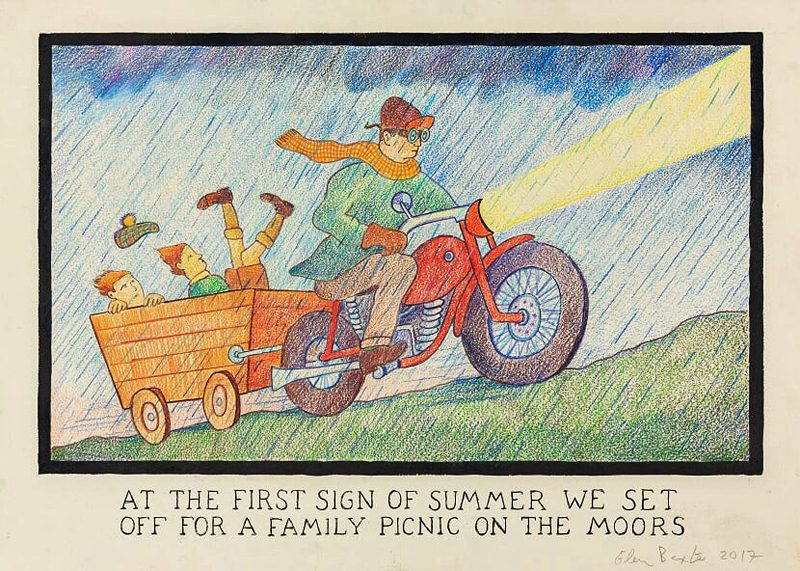

Hunslet shaped him, introducing him to surrealism before he even knew what it was. As a youngster, in the fifties, his stammer meant he’d ask for a six penny bus ticket when going to Roundhay Park. (The real price was a lot less, but he couldn’t say ‘four.’)

One time he was sent to buy some shirt collar straighteners from the tailors. He was so absorbed in practising the words that it wasn’t until he’d asked the shopkeeper for the items that he realised he was in the furniture shop next door.

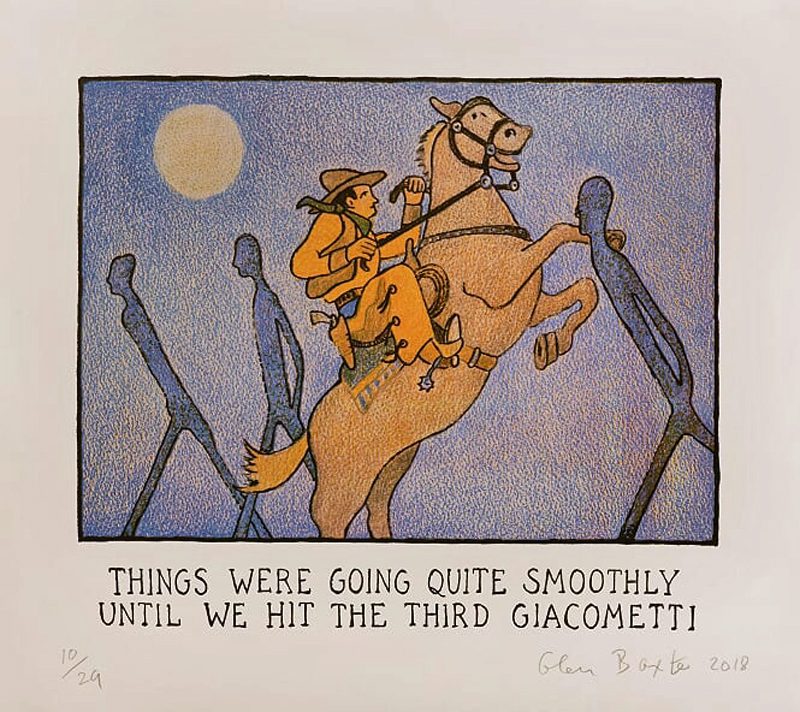

Mix in a dose of slapstick (he saw Laurel & Hardy on their last tour at the Empire Theatre on Briggate), the Marx Brothers and cowboy movies at the Jack Lane and Dewsbury Road cinemas, and you have some of the ingredients of work on display in Unhinged in Hunslet.

‘Saying the right thing in the wrong place’ is Baxter’s description of the latent surrealism he encountered as a child, and then discovered at Leeds College of Art.

After the talk we make our way to Blenheim Walk where there’s more work on display. I ask Baxter about his development as an artist.

“That spirit of anarchy was what I really longed for and found in art. Art was full of naughty boys like [French symbolist] Alfred Jarry, and [composer] Erik Satie, all these great pranksters. They were serious, but it looked like fun.”

Encouraged by ‘Mr Newton,’ his art teacher, he pursued the artistic path, but it wasn’t quite what he expected.

“I came to Leeds College of Art and it was all formal abstraction. It’s not what I really wanted. I wanted something a bit wilder, so I was in trouble. But I survived it, mainly thanks to people like Ed O’Donnell (jazz musician, life model and lecturer).”

As we walk over the Inner Ring Road, Baxter mentions some of the other Hunslet literati like Billy Liar author Keith Waterhouse and playwright Willis Hall. But his main influences come from further afield.

“The first time I saw a Giorgio de Chirico painting, I didn’t know what it was but I liked it. I was intrigued. I wanted to be drawn into that world of mystery, absurdity and surrealism. That opened the doors for me, because my life was already like that so I needed something to reflect it. And that seemed to be the way forward.”

Unlike Billy Liar’s William Fisher, Baxter escaped to London (he lives near The Oval on the South Bank of the Thames) and made his mark as a poet. Invited to New York in 1974 to give a reading, he ended up mounting a show of his words and pictures at the legendary Gotham Book Mart.

Struggling to get any recognition at home, he contemplated upping sticks and moving to the US. He was offered a book deal by a Dutch publisher, which was enough to keep him on these shores.

Some of the work in the exhibition references Leeds and Yorkshire. He says the French really like the Yorkshire stuff. And they really like him. His work has may featured in international publications and exhibited from New York to Tokyo, but the French have a special place for him in their hearts. He’s been given a medal of honour, the Chevalier de Ordres des Lettres des Arts by the government, which involved being “kissed by a French man in the Embassy.”

The visuals hark back to old comics. He describes trying to achieve the saturated colour that appeared on the cheap paper used for the Rupert the Bear annuals when he was a kid, and was lost when they changed the paper and went glossy.

There are common themes: vikings, cowboys, cacti, vegans and recurrent words. I ask about the words, “It’s about the sound of the word. And sometimes the words look strange on the paper.”

“There’s a disconnect between the real world and what’s in my brain. It’s like a strange dream world where you’re not sure where one thing ends and another begins. And I think that the words came about by having all these stumbling blocks because I couldn’t say certain words, so they became very important. And the look of them also, its physically important.” It is almost as if he sees them in three dimensions.

“You have to get the right combination.” He cites 2014’s ‘Clandestine meetings of the Jane Austen Society were held every other Thursday,’ which features a drawing of three silhouetted cowboys on horseback.

Most of his work is one-liners with an image, but he has produced two “what’s now called graphic novels” – an autobiography, His Life: The Years of Struggle, and a detective story, Loomings Over the Suet.

At the mention of suet I remember the book I’ve brought Baxter as a gift to say thanks for the interview (a copy of A Taste of Leeds by food historian Peter Brears which contains recipes and illustrations for old, local staples like Brigg-Shots and Poverty Cakes). Looking through some of his works earlier in the week I got the impression that this was the work of a man that likes his food.

“Yeah I love it.”

As we turn onto Woodhouse Lane, two hi-vized workmen are shovelling tarmac into a hole.

“That’s good old Yorkshire grub,” deadpans Baxter. “Get a plateful of that down ya. It’ll sort you out.”

As we reach the Blenheim Walk campus, (where there are more Baxters on display viewable by appointment), I turn off the tape recorder and follow Baxter into the revolving doors. A group of his friends, family and fans are waiting in the foyer. I exit the entrance, but he remains in for two or three more revolutions.

The morning has been peppered with names of literary and artisitc influences, with a definite gallic flavour. To the aforementioned Jarry and Satie are added [poets] Raymond Rousel and Andre Breton, plus [Dadaist] Marcel Duchamp. Baxter is as Rive Gauche as he is South Bank.

Hunslet is being transformed again. New building work is scouring and cutting and pasting the landscape. Will we see some recognition of the literary lives it helped to mould? How about a Willis Hall next to a Waterhouse Boat Lane on the river set in the cactus strewn, wide open spaces of a Glen Baxter Prairie?

Unhinged in Hunslet is at Vernon Street Gallery, Leeds Arts University until 11th April 2019. More information here.

ROBERT KILNER has appeared in The Idler magazine where he was described thus… ‘Rob is a Leeds office worker who becomes a flâneur for an hour a day.’