In the last of their Great British Art Debate exhibitions Museums Sheffield open The Family in British Art, a show which brings together venerated historical works with big name contemporary pieces to try and puzzle out what that many-headed beast ‘the family’ might look like. The results are pleasingly ambiguous and just as each of our definitions of family might be slippery, when seen through the prism of this exhibition, it is by turns comforting, unsettling, nostalgic, solitary, limiting and liberating.

Just as we enter our own family through childhood, this is the first section of the exhibition. Far from being filled with mawkish pictures of cherubic babies the works here needle at our notions of youth. William Hogarth’s House of Cards looks at first glance like some privileged youngsters having a jolly play date and yet, the closer you look the more their ‘play’ seems to be an allegory of adult conflict and trauma. The children themselves are creepily adult too, lords and ladies in miniature, the only clue to their age is their stature and huge haunting eyes. This contrasts tellingly with Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough’s paintings dating from a time when childhood became acknowledged as a distinct state rather than adulthood-in-waiting, the children depicted here have a rosy bloom that Hogarth’s Mini-Pops lack. Close-by, Paul Graham’s contemporary photograph of a toddler transfixed by an unseen television has the unsettling posture of an adult viewer, while his grip on the remote control mirrors the 17th century picture of a young boy holding a coral teether opposite. At the centre of these conversations between old and new is a Grayson Perry vase called Difficult Background. The cheery frieze suggests an idyllic 50s childhood in the mode of the Peter and Jane books, while scratched images on the surface of the ceramic tell a different story.

Such lively dialogues and uncanny echoes between works contemporary and historical populate every section of the gallery. In ‘Inheritance’ we find a huge loan from the National Portrait Gallery of Sir Thomas More, his father, his household and his descendants. Commissioned by one of More’s grandson after his grandfather’s reputation had been posthumously restored, this is a big statement of genetic propaganda. Opposite we get a pap’s-eye view of Prince William and Kate Middleton cavorting in one of Alison Jackson’s brilliant mock-ups reminding us that, especially latterly, with the inheritance of privilege also comes the burden of fame. A poignant reference to genetic inheritance can be seen in Donald Rodney’s In the house of my father, a photograph in which the artist cradles a tiny fragile house in the palm of his hand, The house is constructed of his own skin, removed in one of many operations to treat Rodney’s sickle-cell anaemia passed down through the male line.

in Parenting one of the star pieces is My Parents by David Hockney which shimmers with the same vivid colours currently on display in his block-buster landscapes at the Royal Academy. The light traces the different poses of his mother and father; she serene, still and focused on her son; he distracted, fidgety and uneasy with the scrutiny. In contrast to the sentimentality which might pervade a section on parenting Mary Kelly’s Post-partum document records her son’s developing writing skills with the keen eye of a sociologist as well as that of a doting mother, the work’s presentation on slate is both curiously cold and impressively biblical.

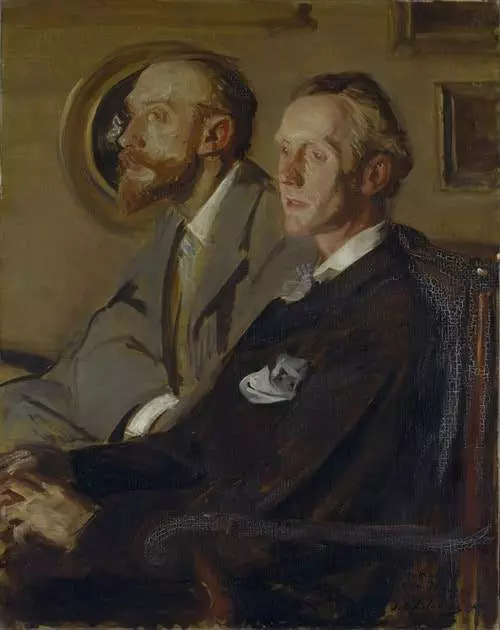

It’s hard to keep any sense of brevity when writing about this stunning exhibition which crams the Millennium Gallery full of knock-out works and big names which ricochet off each other. If there’s one criticism it is that although its presentation of The Family is ambiguous in tone it does largely centre round a traditional, heterosexual family of blood relations. Only Jacques-Emile Blanche ‘s Portraits of Charles Shannon and Charles Ricketts overtly references a same-sex couple and only Ted Duncan’s Absent Friends acknowledges that some people grow up without their birth parents. That said Museums Sheffield have included a new commission from photographer Jonathan Turner comprising a series of pictures of Sheffield families, many of whom reflect non-traditional domestic arrangements.

It’s a chastening thought that given Arts Council England’s recent decision to deny Museums Sheffield Renaissance Funding which results in a 30% cut to their budget, this may be the last exhibition of this size and quality to be displayed at the Millennium Gallery. Reduced funding and staffing levels will mean that Museums Sheffield will not be able to negotiate such high-profile partnerships (this exhibition was produced with Tate Britain, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums, Norfolk Museums & Archaeology Service) or the loan of such valuable and important works. You can read more about the funding crisis here.