In which PHIL KIRBY talks about lampposts mainly…

In 1956 Arnold Machin (who went on to design the queen’s head on all UK coins and stamps, thus becoming the most well-known artist nobody has ever heard of) chained himself to a lamppost in Stoke-on-Trent.

The local council was planning to replace this particular lamppost, a graceful, curvaceous cast iron beauty, with a modern, linear and strictly functional concrete item. As the newspaper put it, “For six hours, Mr Machin – 46 years old, a little thin on top – sat with his back against the lamp. Beside him sat his artist wife, 34 year old Patricia. They held an umbrella over their heads to shield them from the sun. They read a book: The Seven Lamps of Architecture, by Ruskin.” When the police arrived they were reading The Lamp of Beauty, which is half-way through the volume.

Machin got lucky. The workmen who arrived soon after the police to remove the lamppost scratched their heads, had a cup of tea, discussed in a calm and civilised manner what they should do, and decided to offer a compromise. The lamppost had to be replaced, that was their contract with the council. But if Machin agreed to abandon his protest the workmen offered to carefully remove the treasured object from its present station and deposit it in Machin’s garden for him to tend and admire as he saw fit. The lamppost remained there for half a century, surrounded by roses.

I can’t help but think we were better people back then.

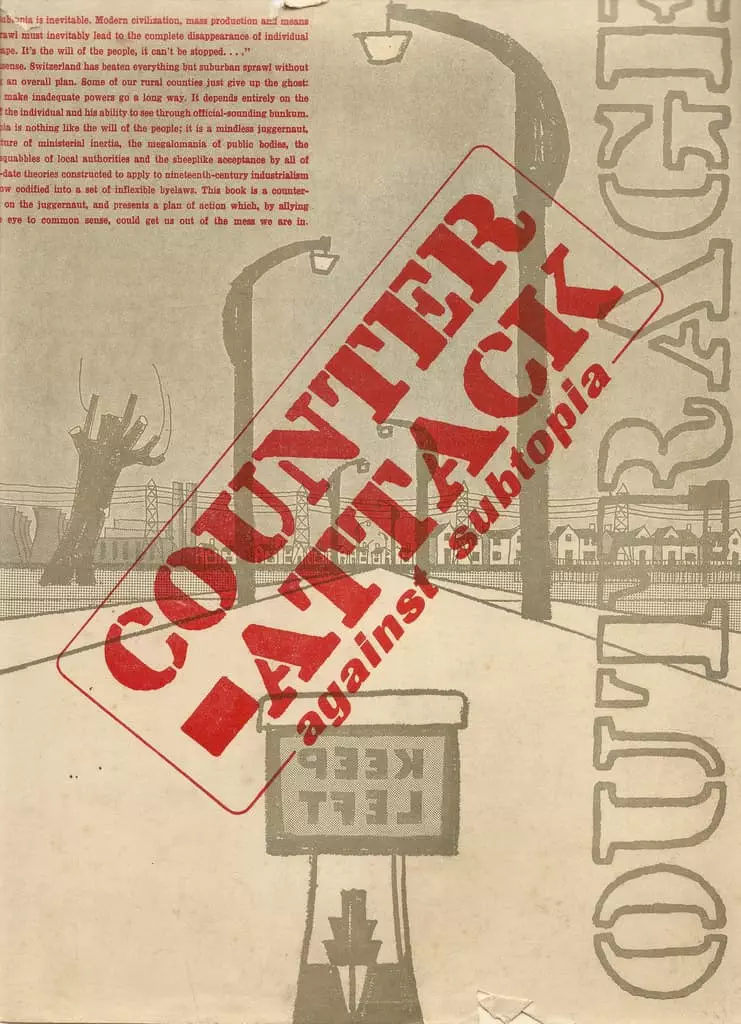

The word Machin used to indict everything he saw wrong with the world, Subtopia, was coined by Ian Nairn a year or so before this incident in a couple of pieces he wrote for the Architectural Review. Outrage, the first piece, became the most famous edition in the AR’s 113 year history, and was a bruising, bare-knuckled attack on the post-war world Nairn saw being built around him – bad design, shoddy materials, dreariness, dispiriting saminess everywhere, lack of imagination, visual clutter and truly appalling lampposts. To quote the manifesto (and I could quote the whole thing it’s so good);

Places are different: Subtopia is the annihilation of the difference by attempting to make one type of scenery standard for town, suburb, countryside and wild. So what has to be done is to maintain and intensify the difference between places … attempt to make life more rewarding, more healthy, less pointlessly arduous. …That is a job for all of us, and the only qualification we need is to have eyes to see. You have eyes to see if you have been exasperated by the lunacies exposed in these pages; if you think they represent a universal levelling down and greying out; if you think that they should be fought, not accepted. Your armoury is your ability to see and reason; your target is the stuff shown here.

I’ve been thinking about Subtopia and Arnold Machin’s aesthetic intervention for the past week or so, since we decided to have a go at setting up a Leeds Modernist Society. Is there anything worth chaining yourself to as a protest?

It’s plain we aren’t short on Subtopia in and around the doughnut of despair. Some of it the product of a modernism – misunderstood as mass produced functional form and simplified into a cheap and cheerless style – that became rampant soon after Nairn wrote his polemic. It’s a cliche, but there really are “concrete monstrosities” that blight the city. Stop a minute, look around, engage your reasoning faculties. This is bad, isn’t it?

Imagine holding your hand up and admitting, “I did THIS!” That entrance isn’t fit for the front of a rabbit cage, surely?

And, if anything, the street lamps are even worse than they were in the ‘50s. What the hell would Nairn or Machin make of this?

Or this

Or… I could go on.

Yes, the city isn’t short of Subtopian low points. Drab, dingy, dim and borderline derelict. But that’s not news. And I doubt anyone today could even find any piece of street furniture worthy of preservation. Would you want this in your garden?

Not that a council employee these days would have the autonomy to enable that to happen.

None of this makes us angry any more. Outrage is over. We’ve become oblivious to the ugly. We pass it by without a thought. Subtopia has sunk into our system.

So it’s been interesting this week to see some remaining embers of civic outrage fanned over something that on the surface would seem an example of anti-subtopia; SOYO.

I can’t do better than quote our friend Chris Nickson here, who wrote this to the council:

SOYO is bright and shiny. It positively effervesces with ambition and excitement. It’s all about the culture, and who can complain about that? Even the lampposts are designed to fit the masterplan.

Well, let’s think about that name for a start. SOYO. Full caps… Unforgivably asinine. But I’ve ridiculed that before.

My main problem with this – apart from Chris’s argument that it’s simply a branding exercise designed to erase history – is that it’s a logical development of subtopia, not its antithesis. Subtopia squared.

Fewtopia.

SOYO; could be anywhere, it’s somewhere and nowhere, and it’s no place much.

It’s not Orwell’s 1984, shabby and monochromatic, reeking of cabbage and stale tobacco. It’s more Huxley’s Brave New World, colourful and comfortable, where your every need is catered for and an app for every passing desire. A space to live, work, enjoy and be entertained… but where there’s no place for dissent.

And only if you can afford it. “Luxury modern living” indeed.

Read this sentence from the architects website. And go look at the accompanying pictures with Nairn’s reminder that you still have the ability to see and reason.

Our aim is to combine high-quality, contemporary landscaping, that meets informal building geometry to ensure a pedestrian-friendly space.

If this sentence was architecture it would be a mud hut. And it wouldn’t contain enough straw to keep it upright. The clauses are trowelled on top of each other in gloopy lumps, there’s no scaffolding holding the thing up and the whole mess just sags in the middle.

What the hell is “informal building geometry”? Look at the buildings…I don’t know about you but this geometry looks pretty rigid to me, Like it could have been designed on an etch-a-sketch.

The rest of the passage details what the development will “accommodate”, “restaurants and city living” to “new bars… and some of the biggest public green spaces inside the city.”

True, there are some decent benches to sit on if the weather’s nice – no back rests though, so not ideal for everyone – trees for shade and some tasteful landscaping. And nothing says “vibrant” more than artisan sausages and authentic falafel hawked from the back of a converted camper van, does it! I’m just not exactly sure this space counts as public? It probably won’t be fenced off in the manner of City Square (remember when our City Square was a genuine public space and not mostly a private beer garden?) but it won’t need to be. The “undesirables” will be moved on should they ever stumble upon the place so as not to disturb the quiet enjoyment of more appreciative consumers of the cultural ambience.

I wonder why no architects drawing ever includes the security guards? SOYO will be privately policed, no doubt about that.

Obviously SOYO is not for everybody.

Still, if we could only get them to drop that name… but that’s probably futopian of me (a futile daydream.)

Not like me to disagree with anything you say Phil but I think the late Ian Nairn is probably on my list of urban critics labelled “who not to like” along with the late Patrick Nuttgens and still alive I believe Jonestheplanner .

I think the danger of what you are getting yourself involved with here if I may say so is a form of nostalgia which can be either a good thing or a bad thing. I could ague either way but here I want to suggest may be not so good. Why?

A couple of interconnected reasons – first it detaches you from the potential of the present. This can be seen in two ways either a celebration of all the things in the built environment (or should that be townscape) that fall into the “so bad it’s good” category. You can indulge yourself in the horror until it becomes pleasurable and wonder what will emerge next with a sense of expectation and delight knowing that as a building it may well be around for some time. The other possibility is to identify the horror and critique it for what it stands for to this extent some historical reference may be needed but we need to say exactly which reference is being made – so for me Nixon’s reference to the distant history of Quarry Hill is irrelevant what is worth recalling are the flats which were previously there and who built them and for what purpose. This said to be the difference between positive nostalgia for a specific and pertinent lost future and a negative nostalgia for something more mystical or illusionary.

This brings me on to a second point about civic nostalgia that links to the first. Who is to judge and on what criteria can the past be seen as in some way better than the present. So being specific what is Nairn exactly valuing against his view of the disappointments of Subtopia. This seems to be something around the aesthetics of place and individual locales being undermined by imposition of either random acts of visual violence or often the architecture of modernism. There are several points that can be made against this, leaving aside for the moment that these are very much the arguments of a specific time whose relevance which we must judge against conditions of today. I’ll deal with place first. I go over the top and say emphasising place difference is simply nativist self-indulgence. Places have more in common than that which divides them. Of course, they are different in many ways but in the broader picture they are all interconnected and are organised around common issues. So lets down play place.

My next “blast” would be to try and look at the aesthetic criteria Nairn and his ilk so assertively apply. Usually I would say they are drawn from some catalogue of a golden age or should that be golden chain of architectural theory going back to Vitruvius and perhaps reaching its zenith in the Victorian era in Britain. I won’t comment on the political baggage this carries because it should be self- evident. Where this coheres with a point I made earlier about the context of Nairn’s writing is that at heart it was anti-modernist. This might be OK if the reference was not back but to alternative present or future available at the time. Clearly things move on and what Nairn denigrated is now subject of new and renewed interest just as was the case with Victorian conservation in his time.

When and what is a mess? Building on the last point today we are possibly (dare I use the term) inclusive around aesthetic criteria in the built environment or is just me? So just as we have seen brutalism come back as a focus of interest which no doubt angers nostalgists. So, no doubt will todays styles be revisited in the future. In the same way I’m not sure whether celebrated is quite the right word or even that aesthetic criteria are relevant at all but there are those who enjoy horror of horrors electricity pylons, the populism of the informal shop frontage, the atmospherics of wastelands etc.

So, I would say get with the Zeitgeist of today’s developments soak in the shallowness they offer or critique them for what they are now not out of nostalgia based a view point more reactionary than it might first appear.

A recent article which touches on nostalgia and less elitist attitudes to preservation of the urban environment: https://thebaffler.com/latest/the-archivists-of-extinction-wagner

Unfortunately I don’t necessarily agree that in the words of the author “resistance to change in the age of neoliberal capitalism is futile.”