Simon Lindley and Principals of the National Festival Orchestra. Leeds Town Hall. Monday 15th October 2012. Review by Dan Potts …

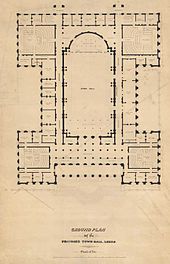

The effects of Sunday night insomnia can linger well into the dreaded working day that follows. That which was left undone on Friday oppresses with Damoclean impoliteness, only to re-emerge and be met with jolts of jitter-making adrenaline. Stress can make a savage of anyone. A temporary haven of lunchtime music is available to all in Leeds city centre on Mondays, with the power to transport her workers from the absurdity of inner turmoil to the sublime. The Leeds Town Hall stands in the civic quarter of Leeds in architectural and cultural ambience sufficient to inspire the civility to which the majority of us aspire, despite mercenary attrition. Within is the florid, marbled and decorous concert venue – The Victoria Hall – that on the 15th October played host to an event that went some way in soothing the breast of this savage. If the music inspired and energised, an engagement with individuals from the major part of the audience soothed with sagacity and tranquillity, for they were mostly pensioners. Intellectual intrigue came in the form of the music-related, contextual information from Simon Lindley, whose dry humour provided a different perspective and thereby gave the spirits a lift. Dr. Lindley, on the organ, was joined by the principal string players of the National Festival Orchestra. They gave a fairly conventional programme.

Handel came first with a work composed originally as preludial material for his oratorios: ‘Concerto V in F’. The Larghetto/Allegro began, as expected, fairly slowly with organ-tutti antiphony soothing through the fruity choice of timbre, which was melodically both innocent and sagacious. A light, crisp organ timbre spoke merriment in the Allegretto via many passing modulations and ascending sequential passages that imparted a hope that was resolved perfectly. However, this was a rocky start for the strings where glitches were discernible in the rhythmic execution. Alla siciliana was the second movement, which spoke longingly in lulling six-eight time via sequential, descending suspensions. An unresolved dominant seventh led intriguingly into the final Presto. Much faster of course, the dance-like quality of the movement disguised the imperfections in the rhythmic and melodic execution of the strings. Here, the organ declared with cadential resolution the end of passages in the strings in a crisp, metallic timbre.

Next came the famous ‘Adagio for Strings and Organ’ by Albinoni. Now the strings were excellent, imparting great profundity in tandem with the organ. This piece stood out from the rest and was the star of the show. Tasteful blended and contrasting dynamics spoke with distinction. No vibrato was applied by the ensemble, which heightened the gravity of the work until very moving, mournful solo passages were played rubato by Sally Robinson on an ‘Italian violin made in 1760 by Andrea Molia’. These solo passages seemed to crystallise into an aural state of mind a deep sense of disappointed longing. The famous bass line continued with doleful, unrelenting regularity, underpinning harmonic tension followed by resolution.

Stanley followed the Albinoni with two movements of ‘Concerto No.3 in G’ on the organ only. This allowed the string players to rest and recuperate after their emotional exhaustion. The Adagio began with simplicity and innocence only to develop cheekily with unexpected passing modulations and frustrating the listener by repeatedly resolving with imperfect cadences. The Allegro, in which we were presented with a descending, sequential passage resolving on the relative minor, amused with repeated harmonic progressions. The playing style was so very straightforward and brusque to create an hilarious impression of the tongue-in-cheek. Mozart came next with a work that was originally composed for the Archbishop of Salzburg: his ‘Epistle Sonata in D’. Typical Mozart agitation and slight syncopation (for the time) led into repeated, bare unison passages followed by greater complexity in antiphony. The execution in the strings was accurate but seemed to lack a degree of energy. However, this dragging quality was due to the acoustic of the room. It might have been that the players were performing as though there were either greater resonance in the chamber, or as though they were recording with reverb. It was refreshing and interesting to hear it this way nonetheless.

Handel opened the concert and he closed it, this time with ‘Concerto in F (Second Set) – the Cuckoo and the Nightingale’. The Larghetto, which was perfectly paced, spoke call-and-response repeated figures with the tutti over different harmonic permutations, resolving on the dominant of the famous second movement. Now, for the Allegro, where the onomatopoeic cuckoo call went fugato to begin with, the toccata-like passages with initial two-note agitation resulted in cadenza-like solo passages on the organ. The melancholy third movement, another Larghetto, was a reflective conversation between organ and strings. Dance-like, positive passages repeatedly resolved on the relative minor. The fourth movement, another Allegro, was performed with great energy and verve as organ-tutti call and response brought each other to a variety of tonal areas. This was a rallying close to yet another high quality, Monday lunchtime concert at the Leeds Town Hall for which payment is made on a voluntary basis.