PICASSO: From Cubism to Classicism, 1915 – 1925 (Skira Editore, £35)

With Tate Modern’s landmark solo exhibition of Pablo Picasso’s work from the thirties, a beautifully produced, exhaustive new book explores the artist’s evolution in the years between the Great War and 1925.

Edited by Oliver Berggruen and Anunciata von Lichtenstein to accompany an exhibition at Rome’s Scuderie del Quirinale palace earlier this year, Picasso: Between Cubism and Classicism, 1915 – 1925 (Skira Editore) is a fascinating account of a period when great turmoil in the artist’s life was echoed by even greater turmoil in the world around him.

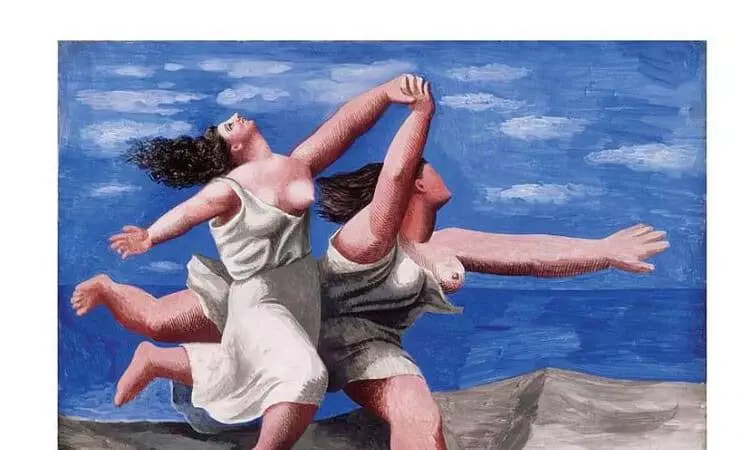

Picasso was still in Paris when war broke out in 1914. With friends either enlisting to fight, or else being forced into exile, the artist was left behind to work in a sort of splendid isolation. In 1915, Picasso painted Harlequin, an early attempt to combine Cubism with a more fluid figurative style. Soon after French poet Jean Cocteau succeeded in persuading him to collaborate on an ambitious one-act ballet, Parade. It would be ‘the greatest battle of the war,’ the poet is reported to have told friends later and Picasso ‘his greatest encounter.’

The pair travelled to Rome in 1917, accompanied by Sergei Diaghilev of the Ballet Russes, whose staging of Stravinsky’s The Rites of Spring a few years earlier had provoked hostile reactions. Irritated by Cocteau’s outlandish foppery, Picasso’s relationship with the poet was often fractious. He considered the self-conscious nature of Parade to be a consequence of Cocteau’s unwarranted affectations, and his work on the set design reflects his deliberate movement towards a simpler, more fluid form of expression.

There is no doubt, Picasso found Diaghilev an inspiration. The book delights with the plenitude of its sketches, maquettes, notes and finished designs emerging from their work together. Von Lichtenstein’s painstaking account of the genesis of Parade is exemplary. She writes with lucid precision, capable of distilling the essence of Picasso’s collaborative achievements and judiciously salting her narrative with revealing anecdotal evidence.

With Cubism under fire for its so called Germanic intellectual sympathies, and new movements Futurism and Dada openly courting dischord and censure, Picasso’s need for respite was an act of self-preservation. Indeed In a world which had descended into the Hell of mechanised, mass-industrial slaughter it proved to be a prudent move.

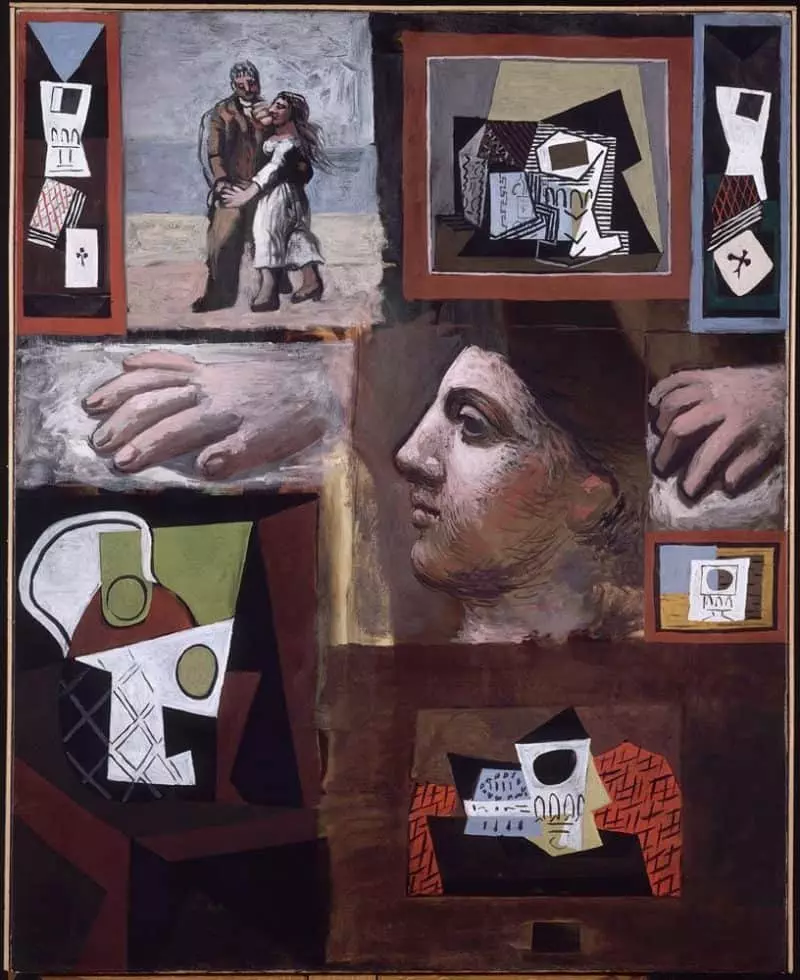

Between 1915 and 1925, Picasso tapped into a rich seam of creativity. Between Cubism and Classicism draws together the various strands of these years. Many of the works are revealed here for the first time – abandoned experiments with Pointilism, surrealistic sculptures and photo-montage – and provide a rich context for the paintings and theatre exhibits which typically exemplify this period in the painter’s life.

It is a remarkable work of curation: the authors have unearthed a wealth of personal correspondence, photographs and postcards, each having its own narrative to impart. Some are playful – snapshots of Picasso’s wife Olga gurning for the camera – while others are heartbreaking. When Picasso writes to his friend, Guillaume Apollinaire, to say he is looking forward to the pair being together again in Paris after the war, there is palpable pathos (the celebrated poet would die in the Spanish flu epidemic less than a year later).

Picasso: Between Cubism and Classicism offers fresh perspectives on a period in the artist’s life which is considered as transitional. A restless, energetic Picasso emerges, one rejuvinated by the challenge of new projects, new collaborators and, above all, new beginnings.