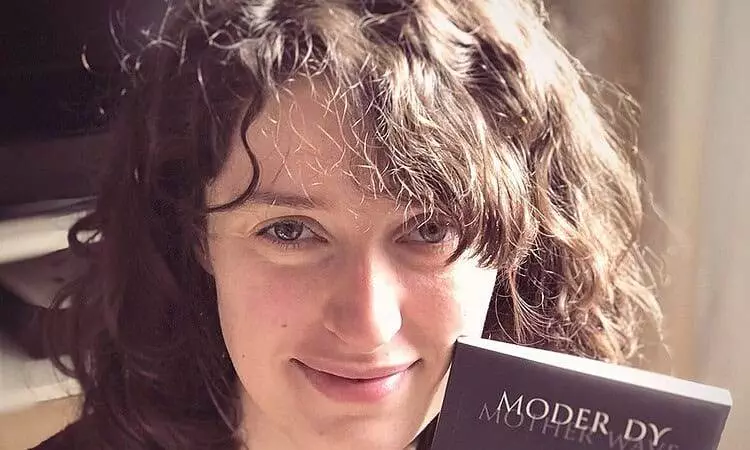

Roseanne Watt with her Edwin Morgan Award winning collection…

ROSEANNE WATT is a poet, filmmaker and musician from the Shetland Islands. Her collection Moder Dy / Mother Wave won the Edwin Morgan Poetry Award prize in 2018. She currently lives in Edinburgh, where she creates film poems and portraits investigating the cultural memory of her home islands. Interview BY JAMES FOUNTAIN.

“I grew up in the village of Scalloway (pronounced “Skall-wa”). It has its own distinct vowel sounds, distinct from other parts of Shetland. I thought Shetland was the centre of the world, I didn’t think of it as strange until I found out by other means – I noticed where I lived was hardly mentioned on TV, for example.

“The first time I left the island was to go on holiday at the age of eight. This is unusual: most children get to leave a lot earlier, but there were six in my family and we didn’t have a lot of money. I saw the tall buildings on the mainland and it was such a shock. I was always aware that there was something beyond the horizon – Shetland was my world for a long time and this still lives with me. I finally left at eighteen to study at the University of Stirling.

“I didn’t realise I liked poetry until I was fourteen – Edwin Morgan’s Glasgow Sonnets were the first that resonated with me. I still don’t know why those poems took root with a girl who lived in a remote island in the North Sea.

“I began taking poetry seriously when I was 19, working in a shop to pay the rent. I began taking night classes led by the Isle of Lewis-born poet Kevin MacNeil, who said if he could become a writer anyone could…he taught me to make every word count on the page. The idea of really considering every word is central to my work.

“I’ve been heavily influenced by Norman MacCaig, George Mackay Brown, and the Island writers such as Robert Allen Jamieson. Poets Christine De Luca and Kathleen Jamie both persuaded me to write in dialect.

“I love both Standard English and Shetland dialect. English has a wider vocabulary, always has a bit more of what you’re reaching for when writing descriptive verse. But in terms of the Shetland dialect – this has greater resonance for my work. The old, extinct language that exists within it as a sub-stratum – I’m haunted by it. It’s exciting, the language of Shetland represents the landscape better than English, I think. There is a harshness to the language which reflects the harshness of environment.

“Shetland has been described as a dead language, but this is not the case. Scots dialect can be very descriptive – a “Scall” is a bay – a “wa” is a wall. Therefore, the village I grew up in from, Scalloway, means “bay of the castle”.

“The first ever dialect poem I wrote contained “hansel” – which translates as wedding or christening gifts, representing the start of something new. Language – no matter what it is, is a gift. It’s nice to be able to give the gift of a Shetland word in a poem. There’s a power-play between English and Scots dialect. A lot of these words are no longer in use in Shetland so I like the idea of revitalising those words, bringing them back into use.

“Reading my poetry aloud is one of my favourite things to do – it used to be my least favourite, but Kathleen Jamie helped me with that.

“I’ve begun making make multi-media film-poems. I couldn’t decide whether to study film or literature. Making films is very similar to making poems – rushes are like sentences. I try to keep it spontaneous – something usually moves me to film rather than something which is planned. Even on a planned shoot you can use this to your advantage.

“The popular BBC crime drama, Shetland, is definitely not representative! There’s not been a murder in Shetland in 50 years! Stephen Robertson does a good Shetland accent – and the rest’s pretty inaccurate, too! It’s beautifully shot, but the dialect is a massive deal to the population – there has been uproar on the island at the poor conveying of the accent.

“It’s hard to be between worlds – I’m definitely not settled. I’ve just finished my PhD about Robert Allen Jamieson and been travelling back and forth from Edinburgh to Shetland. I split my time 50-50 between these places. I’m not really a city girl as I go back nearly every month to shoot films – now I’ve finished my PhD I think I’ll settle into more of a city existence.

“I don’t think this could damage my poetry – having a wide experience of places is a good thing. The thing that’s difficult about Shetland is that it’s a bit far away from book festivals and so on. The Valley at the Centre of the World, Malachy Tallach’s latest novel, describes how people are attached to the island by an elastic band. You either give in to the pull or stretch away, but you are always drawn back to it. That’s a great way to describe it. I remember Shetland through rose-tinted glasses when I’m away.

“Writing Moder Dy was a form of catharsis , a working through elements of my own identity, assimilating my ‘island self’ with her ‘city self’: I’ve always had a dual identity as my mother is from Ireland – sometimes my identity can feel like it’s in conflict, so trying to unify the two languages in my head, of Shetland dialect and Standard English. It’s my personal journey and a necessary one.

“The language question is always going to be there – it’s always evolving and there are always new dimensions to explore. I’ve reached the point where I can write more city poems, I think. I’ve come to terms with Edinburgh a bit more, and now I want to write poems that are in dialect about the city – it will be nice to explore that further.”

Moder Dy / Mother Wave is a rich, confident first collection, engaging in the tricky business of translating Shetland dialect into Standard English. Review by JAMES FOUNTAIN.

What will have caught the eye of the judges of the Edwin Morgan Poetry Award (which Roseanne Watt‘s Moder Dy / Mother Wave won in 2018) will have been the poet’s knack for embedding ancient Scots vocabulary, such as ‘skerries’ (stones) and ‘silkies’ (seals).

There is a brevity to the language and careful placing of vocabulary reminiscent of the great W. S. Graham, the Greenock-born poet who made his way to Cornwall, and won the admiration of T. S. Eliot in the 1940s.

Watt displays pride in the ‘strangeness’ and otherness of Shetland existence, harnessing the thousand-year-old Scandinavian elements of Shetland dialect in her descriptions of landscape and people.

The opening six lines of Raaga Tree capture this otherness :

Ta see me

is ta see

a vodd

wirld, shakkeld

atween tang

an auld nets.

The standard English translation is no less murky (‘To see me is to see/an absent world/caught between/seaweed and old nets.’) which is perhaps the point. Watts has admitted she feels torn between the mainland and Shetland, their differing dialects and people.

A longing for island life is here reflected in the metaphors formed from the language of fishing, and the sense of feeling borne adrift in nature.

White Out‘s sense that in order for the individual to move on and start a life on the mainland, island culture must be burnt out is reflected in the ink which gradually fades to white as the poem progresses:

de island

koomed

wir braeth

gied

lik ess

afore wis.

This is a mystical collection, full of Shetland’s haunting beauty and with the weight of history deftly delivered through Watt’s island dialect.

Moder Dy / Mother Wave by Roseanne Watt is available from Polygon Books here. She is at the Shetland Film Festival from 4th – 29th September 2019. Details here.

Review of Michael Pedersen’s Oyster (with illustrations by Scott Hutchison).