Our series featuring small press publishers from across the North continues with sometime fictional Irishman KEVIN DUFFY of Bluemoose Books, based in Hebden Bridge. Interview by NEIL MUDD

A quick quiz before we start. Colm O’Driscoll is a) an Irish Gaelic footballer; b) one of the villains in video game Red Dead Redemption 2; or c) the nom de plume of desperate-to-be-published writer Kevin Duffy?

“I’d seen in The Bookseller that all the big money was going to Irish writers,” Kevin told interviewer Lucy Macnamara in 2016. “So I changed my name to Colm O’Driscoll, and sent three chapters off to an agent in London called Darley Anderson.”

“He tried to ring me, but obviously Colm O’Driscoll isn’t in the telephone book for Hebden Bridge, so he wrote me a letter and I phoned him back. But of course, I had to be Irish – and I had to be Irish for twelve months, even lying to my two sons saying, ‘If a posh bloke rings up from London asking for Colm O’Driscoll: Colm O’Driscoll is your Dad!'”

[For the record, the answer is a, b and c, though Kevin can be forgiven for thinking it unlikely your average London literary agent would be an avid gamer or a season ticket holder for Cork team, Tadhg Mac Cárthaigh.]

Bluemoose Books, which Kevin set up in 2006 with his wife Hetha, remortgaging their home (“just before the worldwide economic crash!”) to do so, is based in the West Yorkshire former mill community of Hebden Bridge. Kevin lives one town along from writer Benjamin Myers, whose Walter-Scott Prize winning book, The Gallows Pole, was published by Bluemoose in 2017.

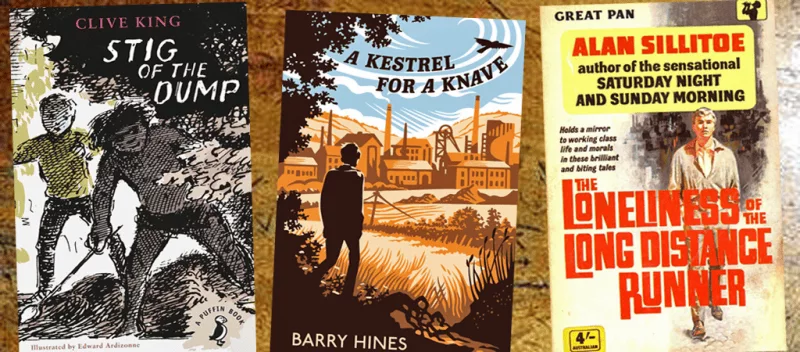

Kevin’s earliest memory as a reader is of Clive King‘s Stig of the Dump. “But the (one) that really got me into reading in a big way was A Kestrel for a Knave by Barry Hines; then short stories like The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner by Alan Sillitoe; books like that.”

All feature loners or outcasts in some way or other as their central characters. “Those were the first ones that got me excited about people I could relate to, and that’s what it’s all about for us at Bluemoose. We can learn from each other if we read about each other’s lives, and those books are about people that were believable rather than ones by Enid Blyton and Richmal Compton.”

That said, the young Kevin was a fan of Jennings. “(It) was just such a world away, but in essence it was a good starter for realising that the world of publishing was upper middle class – and nothing much has changed really.”

At home there were few books. “My parents were very religious. They were from an Irish Catholic background, so the only books in the house were Butler’s Lives of the Saints and the Encyclopaedia Britannica. We didn’t have any reading books, but we did have a library so I used to go there all the time.”

Unable to find work in his native Manchester, Kevin moved to London in 1986, where he worked for library suppliers Cromwell Books in Hounslow before joining Headline. “I was sales rep for London and the Shires which is how I got into sales and marketing,” he says. “I’ve been selling books in one way or another for the past thirty years.”

Kevin once quipped that the parents of Bluemoose Books were bile and anger. Back in the North in the early noughties, he wrote a novel and found an agent, but despite making positive noises, no publisher would take a punt. The demise of the Net Book Agreement [which fixed book prices until it was ruled illegal in 1997] left them increasingly risk averse.

“They were only publishing books that were like books that had become popular or successful. I know that’s a huge generalisation, but as a rule of thumb it’s just the same kind of blancmange they were all publishing. The big thing at the time was Scandinavian noir, so everyone wanted a Scandiwegian writer.”

“So I was just moping about the house and Hetha said, ‘Why don’t you do something about it?’ Initially (Bluemoose) was a bit of a vanity project just to get my book out, but we published another book (The Bridge Between by Canadian writer Nathan Vanek) because I didn’t want it to feel like (one).”

Through contacts in sales and marketing, Kevin was on first name terms with branch managers of Waterstones across the North of England and buyers for the library services: “without libraries, Bluemoose wouldn’t be here today,” he says.

Living in Hebden Bridge, Kevin knew writers unable to find a publisher for their third or fourth book because of the sales margins on their previous ones. Benjamin Myers, for example.

“His commissioning editor said to him [about Pig Iron], ‘Ben, who’s going to be interested in a working class character in a small Northern town?’ That ‘small Northern town’ is Durham which was the theological capital of Europe for two and a half thousand years…”

Bluemoose published Pig Iron in 2012, and it won the inaugural Gordon Burn Prize the following year. Reviewing it in The Guardian novelist Cathi Unsworth wrote: ‘Myers’s poetic vernacular brims with that quality most sadly lost in the Thatcher years – humanity.’

“The most important person in publishing these days is the Marketing Director,” Kevin says. “For a long time it was the Commissioning Editor – if they fell in love with the book, it would get published – but the thing is, Sales and Marketing know what has sold, but they don’t know what will sell. It’s like the advertising thing, isn’t it? Fifty percent of it works, but you don’t know which fifty percent.”

“The worrying thing for me is whether the agent model is really working. When agents say to me they’re really pleased their authors haven’t earned out their advance – basically saying they’re really chuffed they haven’t sold that many books, but the author has still got their hundred thousand – to me, that is not a credible business model.”

If literature is about anything, it’s about seeking out new talent and not about meeting the insatiable demands of shareholders, he says. “It’s an inexact science; so much money is being wasted on unearned advances, but no one’s talking about it because we’re in this archaic, anachronistic twentieth century industry based on a nineteenth century model.”

Bluemoose proudly describes itself as a ‘family’ of readers and writers. “I’m not saying we’re like therapists, but we kind of are,” says Kevin. “We’ll spend maybe twenty four months on a book before we release it, and it’s a collaboration between us and the writer because we both want the same result, which is to get the book into as many readers’ hands as possible.”

“Lots of writers love that kind of passion because they know we’re on their side. I’m not saying that bigger publishers don’t care about their books, but I know as a sales rep you can’t put the same amount of energy and effort into fifty titles. You will have four or five you’ll really push because you’ve got to reach targets; the other forty-five writers are just not going to get the same amount of attention.”

Books by Bluemoose are miniature works of art, from their distinctive covers to the muscular prose they contain. They are a product of the landscape, hewn from the granite of people and place. “First and foremost it’s the stories,” Kevin says. “and, of course, they have to be beautifully written. In Ben’s case, he just immerses you in the landscape.”

“I remember we published a book called Nod, written by a Canadian writer called Adrian Barnes [who died in January 2018]. It’s set in Vancouver. The premise of the story is that people get up one morning and no-one’s slept and they don’t know why. After six days neuroses sets in, then after twenty eight days the brain can’t re-calibrate, so they actually die.”

“I read it as just a fantastic story, so we published it. Then the science fiction world picked up on it and described it as a brilliant dystopian novel. It was shortlisted for the Arthur C Clarke award [in 2013]. Now, I hadn’t read it as a dystopian fiction, I just thought it was a great story.”

“Because we are reading unsolicited manuscripts, we are seeing more and more by writers with talent, than the bigger publishers,” says Kevin. “The agents for them are screening books, not for quality in the first instance, but for how much money they can make out of them.”

“Now I’ll get pilloried for that, but I’m sure that comes into their heads. I speak to agents all the time, who say ‘This is a fantastic book, but we won’t sell enough units.'”

“Apparently sixty-seven thousand thousand is the figure. I don’t know where they get that from. (Bloomsbury) who’ve got three of our Benjamin Myers’ backlist, tell me they loved what (he) published before, but couldn’t make an economic argument for publishing it.”

“If you love something, you publish it and make an economic argument out of that. It’s their job. It’s not rocket science, it really isn’t. But they’ve got some kind of strange obtuse Venn diagram. That’s their alchemy, and if the book doesn’t fit into that, they’re not going to publish it. Very few people know what that Venn diagram looks like…”

Kevin says he has little patience with post-modern literary fiction which to him is just the writer writing about writing. “People want stories in these end-times of Brexit and Trump and Nationalism. We need more and more stories from diverse regions and people, otherwise we’re never going to understand each other and people will continue to wrap themselves in a flag of nonsense…”

Bluemoose has had a number of titles translated into Russian, Bulgarian and Hungarian. It enjoys a strong reputation in the Caucasus. “The first one we had translated into Russian was Falling Through the Clouds by Anna Chilvers. I’ve mentioned it before, but we are one of the few independent publishers to have the same book in English and Russian at Waterstones in Piccadilly.”

I ask about the origins of the name Bluemoose. “There’s a pub in Hardcastle Crags called The Blue Pig, and they had a fantastic sign which looked like a tattoo of an old pig. At the time, I was reading a book about the history of soul music by Peter Guralnick [Sweet Soul Music] and the chapter I’d just read was about a great saxophonist of the thirties and forties called Bullmoose Johnson.”

“I woke up one morning with the name Bluemoose in my head, so we called it that. A mate who lives in Hebden Bridge designed the logo, and – this is where the arrogance and delusion comes in – I wanted a logo for the spine that was as good as Penguin‘s, so when people see the Bluemoose logo they’ll think, ‘That’s a Bluemoose book. That’ll be a good book.’ That’s where the despot comes in!”

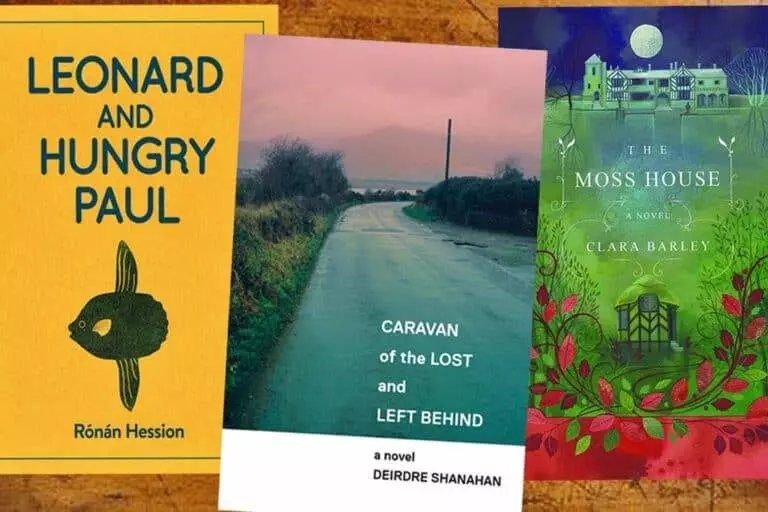

Kevin might just be onto something. Recent publication Leonard and Hungry Paul by Ronan Hession has been receiving great reviews. At the end of May comes The Caravan of the Lost and Left Behind by Deirdre Shanahan, in which a travelling family flee London gang crime. (“It’s about dislocation; it’s about longing, and given what’s happening with Brexit, I think it’s quite apposite at the minute.”)

In July Bluemoose will publish The Moss House by Clara Barley which tells the turbulent true story of Shibden Hall’s Anne Lister and Ann Walker, as they fall in and out of love with each other. “They were the first lesbian couple to get married in York in 1832,” says Kevin. “It’s well known in West Yorkshire and Calderdale that (Lister) was known as Gentlemen Jack.”

Whether it’s science-fiction, folk-noir or Queer history, Kevin Duffy knows it’s people and places that matter most. We began our interview with Colm O’Driscoll and we end it with Gentleman Jack. Both fictional characters of a sort. People like stories…

More about Bluemoose Books here.

Handmade Tales: Armley Press

Hebden Bridge Confidential: Ben Myers on The Gallows Pole